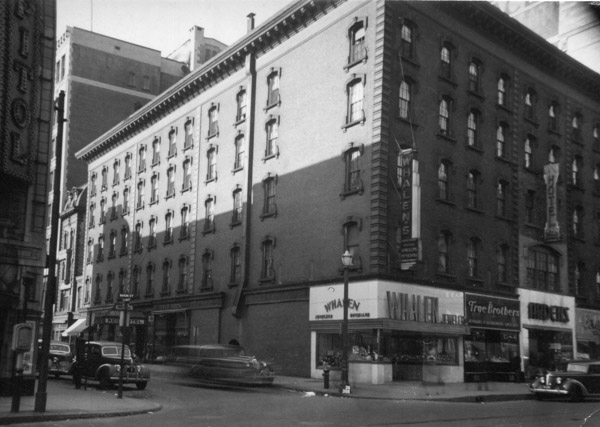

The Forbes & Wallace department store on Main Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The scene in 2017:

For just over a century, Forbes & Wallace was one of Springfield’s leading businesses, with its department store located here at the corner of Main and Vernon Streets. The company was established in 1874, when Scottish immigrant Andrew Wallace formed a partnership with Alexander B. Forbes, a dry goods merchant here in Springfield. They rented space in an earlier building that stood at this same location, and within a decade the two men had built the company into, as described in the 1884 King’s Handbook of Springfield, “the largest and most prominent wholesale and retail dry-goods house in Massachusetts, excepting only some of those in Boston.”

By this point, Forbes & Wallace had purchased the entire building, modifying it to meet the needs of the company’s growing business, but around 1905 the old building was demolished and replaced with a new Classical Revival-style building that is seen in the first photo. Only a portion of this massive building is visible in this scene, though. The eight-story, L-shaped structure extended for a significant length along Vernon Street (today Boland Way), and wrapped around the Haynes Hotel so that part of the building fronted on Pynchon Street. Over time, the company’s complex would come to fill almost the entire city block, including its own parking garage on the western side, and the department store remained a Springfield landmark for many years.

Alexander Forbes has retired from the business in 1896, but Andrew Wallace remained with the company until his death in 1923, nearly 50 years after he had established it. His son, Andrew B. Wallace, Jr., and later his grandson, Andrew B. Wallace III, both succeeded his as president of the company, which remained in the Wallace family for many years. The first photo was taken in the late 1930s, during the time when downtown department stores still dominated retail shopping. Aside from Forbes & Wallace, this section of Main Street also feature its largest competitor, Steigers, along with a variety of smaller stores. The scene in the first photo shows Main Street lined with parked cars, and the blurred figures on the sidewalk and in the street give the impression of a busy shopping district.

In the decades that followed, though, suburban malls began to eclipse downtown stores, and Forbes & Wallace followed this trend, opening satellite stores at the Eastfield Mall on Boston Road and the Fairfield Mall in Chicopee. Around the same time, downtown Springfield underwent several large-scale projects aimed at urban renewal, including the construction of the 371-foot, 29-story Baystate West building, which was located directly opposite Forbes & Wallace on the north side of Vernon Street. Now known as Tower Square, this project was completed in 1970, and included a shopping mall that was connected to Forbes & Wallace via a skywalk.

The Baystate West mall evidently did little to revive Forbes & Wallace, though, and the store ultimately went out of business in 1976. The building sat vacant for the next few years, and it was finally demolished in the early 1980s to make way for Monarch Place, a skyscraper that is just out of view on the left side of this scene. Completed in 1987, it is currently the tallest building in the city, and the original site of Forbes & Wallace at the corner is now a small plaza. There is a small replica facade on the left side, partially visible from this angle, but otherwise there is no trace of the old department store. Today, the only building left from the first photo is the Haynes Hotel, which stands as the only 19th century structure amid a variety of 20th century urban renewal projects.