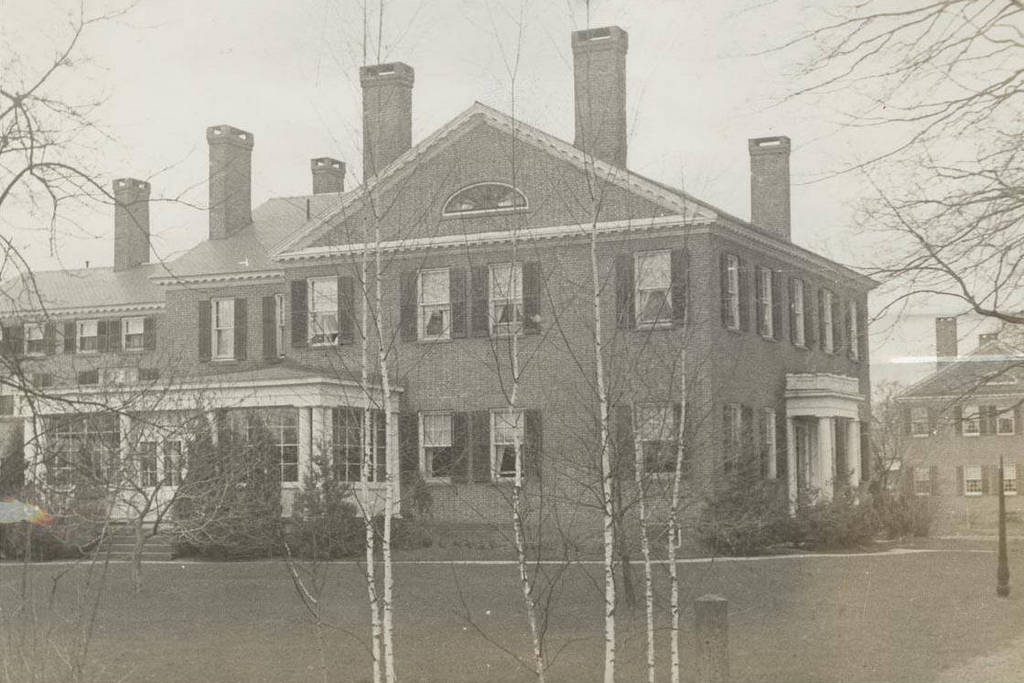

The house at 43 Magnolia Terrace in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

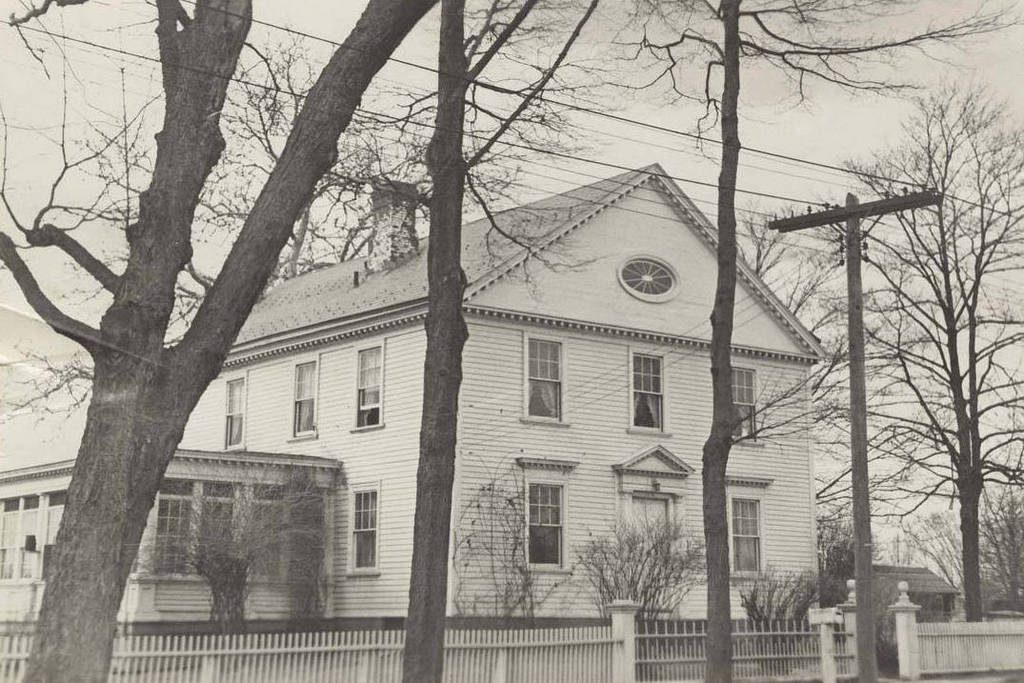

The house in 2017:

Completed in 1925, this house was among the last to be built in this section of Springfield’s Forest Park neighborhood, with most of the other homes dating back to the turn of the 20th century. It was originally the home of Frederick B. Taylor, a merchant who sold doors, windows, blinds, paint, and other such building materials from his shop on Market Street. By the time Taylor moved into this house, he and his wife Eliza were in their 60s, and he only lived here for a few years, until his death in 1929.

Later in 1929, Eliza moved to Longmeadow to live with her daughter, and she sold this house to George and Kathryn Clark, who moved in here along with their three children. At the time, George was the vice president of Springfield’s Third National Bank, and he later went on to become the bank’s president. His wealth was reflected in the 1940 census, which was done only a year or two after the first photo was taken. The house was valued at $16,000, which was a considerable sum at the time, and George’s income was listed as being over $5,000, which was the highest bracket that the census recorded.

After George’s death in 1949, Kathryn continued to live here for nearly a half century longer, until she finally sold the property in 1987. Since then, the house has remained well-preserved, with an exterior appearance that is essentially unchanged from when the Clarks lived here. Along with the other homes in the neighborhood, the property is now part of the Forest Park Heights Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.