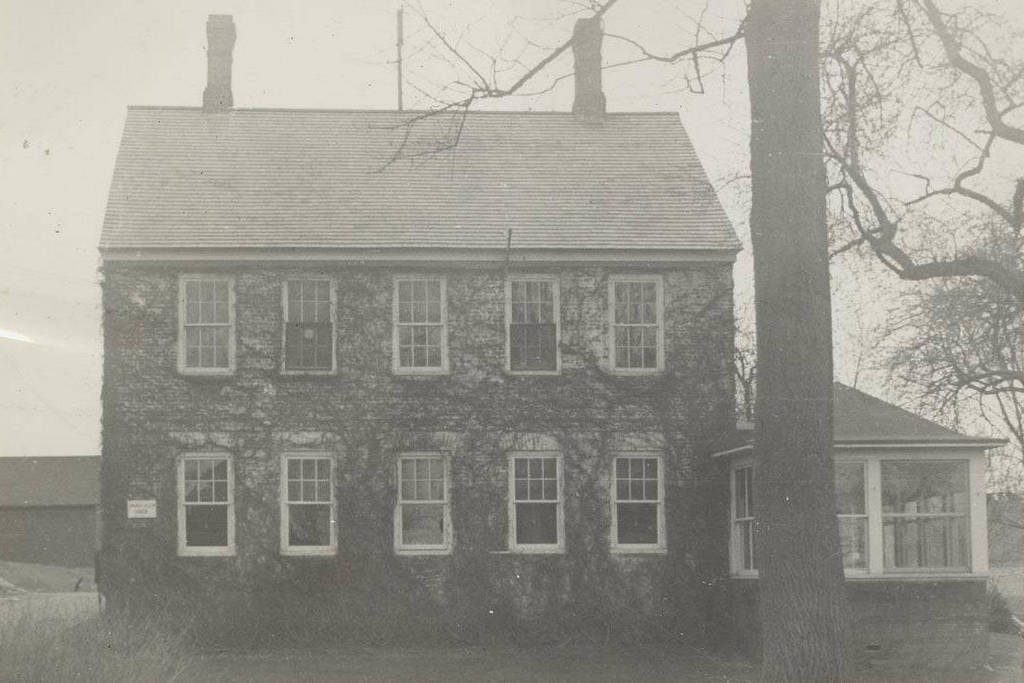

The house at 144 Buckingham Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The house in 2017:

This large Stick-Style home was built in 1882 for Samuel L. Merrell, a Congregational minister who was originally from New York. Born in Utica in 1822, he graduated from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1848 and served a number of different churches in upstate New York. He also served two years in the Civil War, as chaplain for the 35th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, before returning to civilian ministry.

Reverend Merrell, along with his wife Cornelia and their son Samuel, came to Springfield in 1882 and moved into this house around the same time. When the School for Christian Workers was established three years later, Merrell joined the faculty, and also served as the organization’s secretary and a trustee. During this time, the younger Samuel also lived here, working as a traveling salesman for Cutler and Porter, a Springfield-based wholesale firm that sold boots, shoes, and rubber goods.

After Reverend Merrell’s death in 1900, the house remained in his family for several more years, but by 1906 it was purchased by Marcus M. Goodell, who worked as vice president of the Springfield Lumber Company. He and his wife Emma lived here with two of their children, Alfred and Edward, and both were also employed with the lumber company, working as a foreman and a bookkeeper, respectively.

During the 1910 census, 39 year old Alfred was still single, but his younger brother was recently married and living here with his wife Carrie. That same year, this house was the scene of a rather bizarre religious event that made newspaper headlines across the state. Marcus was the leader of a Pentecostal sect that believed, given recent calamities around the globe, that the end of the world was imminent. With this in mind, about 30 or 40 of his followers, including his family, barricaded themselves in the house, believing it to be their “ark” through which they would survive the end of the world.

The end of the world turned out to be slow in coming, and in the meantime the directors of the lumber company became concerned about the fact that Marcus, Alfred, and Edward had stopped coming to work. Finally, several weeks into the seclusion, they threatened to fire Marcus as vice president if he did not come to the next board meeting. The impending apocalypse notwithstanding, Marcus and Edward decided to temporarily leave the house in order to attend the meeting, but they returned a few hours later.

Newspapers across the state had a field day with this story, comparing the large barricaded house to Noah’s ark, and Marcus and his three sons to Noah, Ham, Shem, and Japheth. After the board meeting, the Boston Globe subtly pointed to the absurdity in it all, remarking that “although Mr. Goodell may place the utmost credence in the prediction that the end of the world is near at hand, it is evident that he does not believe it good policy to neglect his business affairs when there is danger of their becoming seriously involved.”

Aside from the board meeting, the Goodells and their followers remained here for most of the summer of 1910, although most of the newspapers seemed to have lost interest by the time they finally emerged from their seclusion. Following this event, they carried on life as usual, until Edward’s death in 1918 and Marcus’s two years later. Their widows, though, would both outlive them by many years, and when the first photo was taken in the late 1930s Emma, at this point in her late 80s, was still living here, along with Alfred and her other son, Irving.

Alfred Goodell evidently inherited his mother’s longevity, because he continued living here in this house for about 60 years, until his death in 1966 at the age of 93. Since then, the house has remained mostly the same, although it is now a two-family home. The exterior retains its decorative Stick-style design, and the house is now part of the McKnight Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.