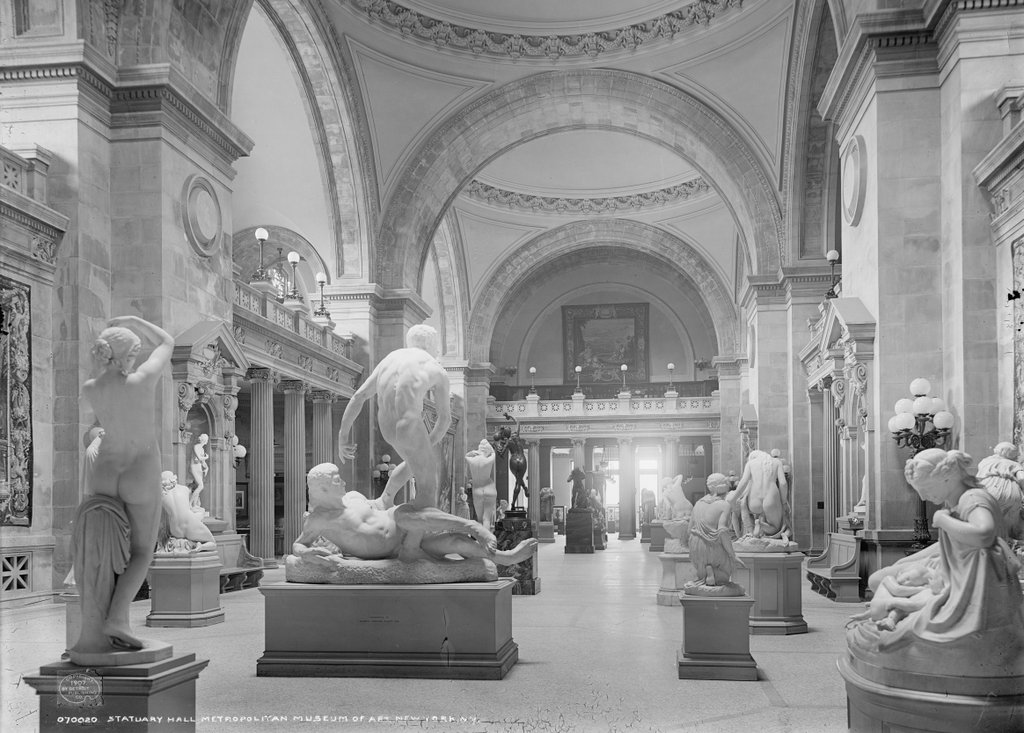

The view looking south in the Great Hall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, around 1907. Historic image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2019:

These photos show the same general view as the ones in an earlier post, although these were taken from the ground floor rather than the balcony. As discussed in that post, the Great Hall was completed in 1902 as part of an expansion of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and it originally served as both an entrance hall and a sculpture gallery. The main entrance to the museum is on the left side, just beyond the columns. Directly opposite the entrance, on the right side of the scene, is the Grand Staircase, which led to the original part of the museum building.

The first photo was taken a few years after this wing of the museum was completed, showing it filled with a variety of sculptures. Some of the notable works here include Struggle of the Two Natures in Man by George Grey Barnard, which was carved from 1892 to 1894 and donated to the museum two years later. It stands in the foreground on the left side of the photo, and just beyond it in the distance is Evening (1891) by Frederick Wellington Ruckstull and Bacchante and Infant Faun (1894) by Frederick William MacMonnies. Other identifiable works include Latona and Her Children, Apollo and Diana (1874) by William Henry Rinehart, located in the lower right corner, and Nydia, the Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii (1859) by Randolph Rogers, which is partially visible on the extreme right side of the photo.

Today, more than a century after the first photo was taken, all of these identifiable statues are still in the museum’s collections, although they are now located in or near the Charles Engelhard Court, where a number of important American sculptures are on display. There are a few sculptures here in the present-day scene of the Great Hall, with the ancient Egyptian Colossal Seated Statue of a Pharaoh in the foreground, and the ancient Greek Athena Parthenos in the distance, but otherwise the Great Hall is used primarily as an entrance hall. There is now an information desk in the center, which is largely hidden from view by the crowd in the 2019 photo, and there are ticket counters at either end of the room.