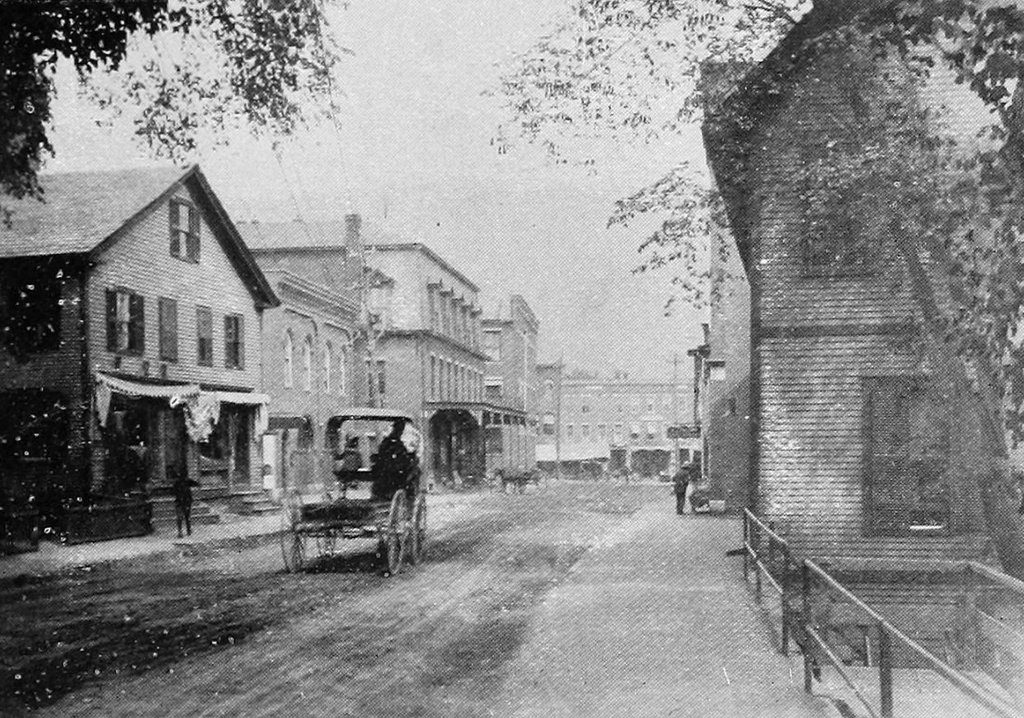

The branch library on Oak Street in the Springfield village of Indian Orchard, probably around 1910. Image from the Russ Birchall Collection at ImageMuseum.

The library in 2017:

Springfield’s public library system dates back to 1857, when the City Library Association was founded. Two years later, the library opened in a room in the old city hall, where it remained until the first permanent public library building was completed on State Street in 1871. Throughout the 19th century, this would remain the only public library in Springfield, but the city also had a number of private libraries, some of which were open to the public. Here in Indian Orchard, a factory village in the northeastern corner of the city, the Indian Orchard Mills Corporation opened a private library in 1859. This library was open to the public, and would serve the residents of the neighborhood until 1901, when a public branch library was opened.

This public library was the first branch library in the city, and was originally located on the ground floor of the Wight & Chapman Block, at the corner of Main and Oak Streets. However, it proved so popular that within a few years it was regularly overcrowded, and a more permanent location was needed. The solution came in 1905, when steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie donated $260,000 to the city in order to build a new central library and three branch libraries. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Carnegie donated funding to build 2,509 libraries around the world, including 43 in Massachusetts, and his 1905 Springfield grant was the single largest one that he made in the state.

The Indian Orchard branch was completed in 1909, opening on March 26 of that year. It featured a Classical Revival design that was popular for libraries of the era, and was the work of Springfield architect John W. Donohue. A prolific local architect, Donohue specialized in designing Catholic churches and other ecclesiastical buildings, but the library was one of his few major secular commissions during his long career. His design also won him national attention, and was featured in The American Architect in 1911.

Nearly 110 years after it opened, the Indian Orchard library is still in use, and it is now one of eight branch libraries in the city. It was threatened with closure in 1982 and in 1990, but it ultimately remained opened and was expanded, undergoing a major renovation and addition that was completed in 2000. This included a large new wing on the back of the building, which is partially visible in the distance on the right side of the 2017 photo. However, the original section of the building was preserved, and today this scene has not significantly changed since the first photo was taken. Because of its historical and architectural significance, the library is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.