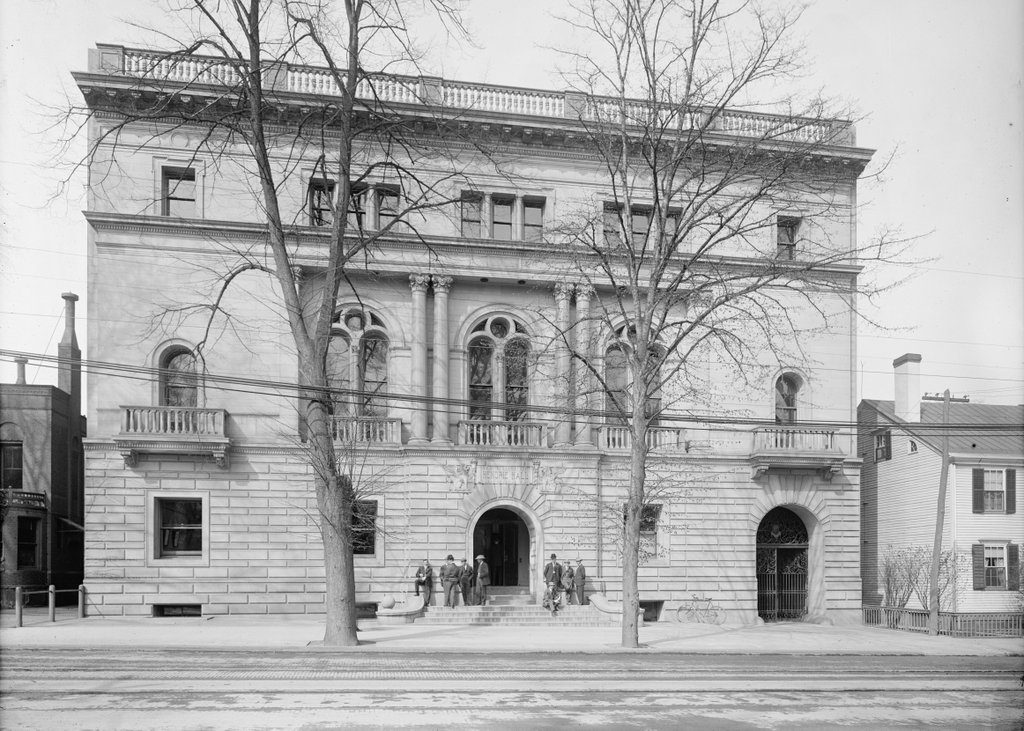

The Ten Eyck Hotel, seen from the corner of State and Chapel Streets in Albany, around 1901. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2019:

The Ten Eyck Hotel was one of Albany’s leading hotels of the early 20th century. It was built in two different stages, but the oldest section of the building, which is shown here in the first photo, was completed in 1899 at the northeast corner of State and Chapel Streets. It was named for James Ten Eyck, a local businessman whose family traced back to the early years of the Dutch settlement in Albany. He was part of the ownership group that built the hotel, and he was also its first official guest, signing his name in the register as part of the hotel’s opening on May 8, 1899.

The Ten Eyck was built in order to meet the demand for a new hotel in Albany. The city’s famous Delavan House had burned in 1894, and 16 people died in the fire. Hiram J. and Frederick W. Rockwell, the father-and-son partnership that ran the Kenmore Hotel, recognized the need for a new hotel, and they helped to form the Albany Hotel Corporation, which was established in 1897 with James Ten Eyck as one of its directors. Work on the new building began in 1898, and upon completion the Rockwells signed a long term lease to operate the hotel.

At nine stories in height, the Ten Eyck towered above its neighbors here on the north side of State Street, as shown in the 1904 photo in a previous post. The eastern side of the hotel, which is visible in that photo, was unadorned brick, but it did feature a large painted advertisement that declared the Ten Eyck to be “positively fire proof.” This fact was touted in contemporary print advertisements as well, likely in order to assure customers that it would not suffer the same fate as the Delavan, whose fire was still in recent memory.

The first photo here was taken only about two years after the Ten Eyck opened. At the time, the hotel was flanked by two older, smaller commercial blocks. On the left side of the photo is the ornate Albany Savings Bank building, which was completed in 1875. However, by the time the photo was taken, the bank had moved to a new facility on North Pearl Street, and this building here on State Street was repurposed as county offices. Directly adjacent to the hotel, on the right side of the photo, is the Tweddle Building. It was built in the mid-1880s, replacing the earlier Tweddle Hall that had burned in 1883, and it featured a mix of commercial offices and retail space.

The Ten Eyck proved to be popular, and in the mid-1910s the owners embarked on a massive expansion project. They purchased the Tweddle Building, demolished it, and constructed a new 17-story hotel building, which opened in 1917. The older nine-story section became the Ten Eyck Hotel Annex, and together these two buildings were used by the hotel for many years.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the Ten Eyck remained one of the city’s most popular hotels. It changed ownership several times, eventually becoming a Sheraton, but by the 1960s it had begun to decline. This was the case in cities across the northeast, where once-fashionable downtown hotels were losing business to newer suburban hotels and motels. A major part of this was because of companies moving away from downtown locations, and also because of changes in transportation patterns. With most people now traveling by car instead of by train, it was much easier to stay at a modern hotel right off the highway rather than navigating downtown traffic to reach places like the aging Ten Eyck.

As a result, the Ten Eyck closed in 1968, and both buildings were demolished several years later. The old Albany Savings Bank on the left side of the photo appears to have been demolished around the same time, and the entire two-block section between North Pearl and Lodge Streets was redeveloped. Now completely unrecognizable from the first photo, this scene features several modern buildings, including an office building on the right and a Hilton hotel on the left.