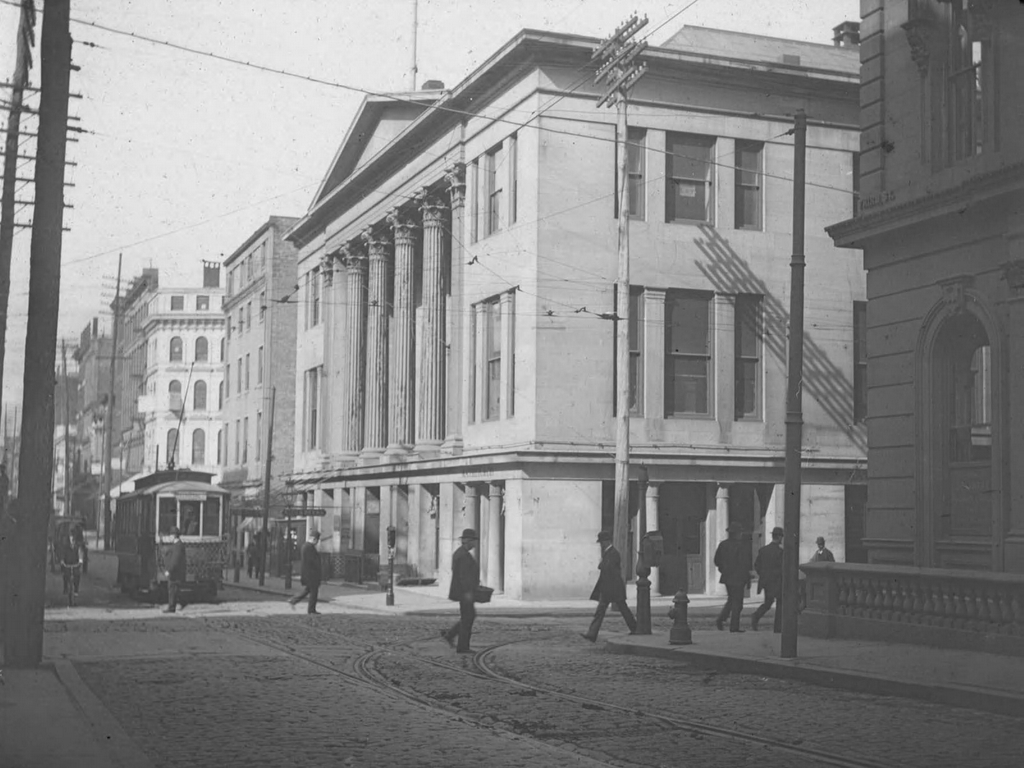

The Vermont State House in Montpelier, around 1904. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

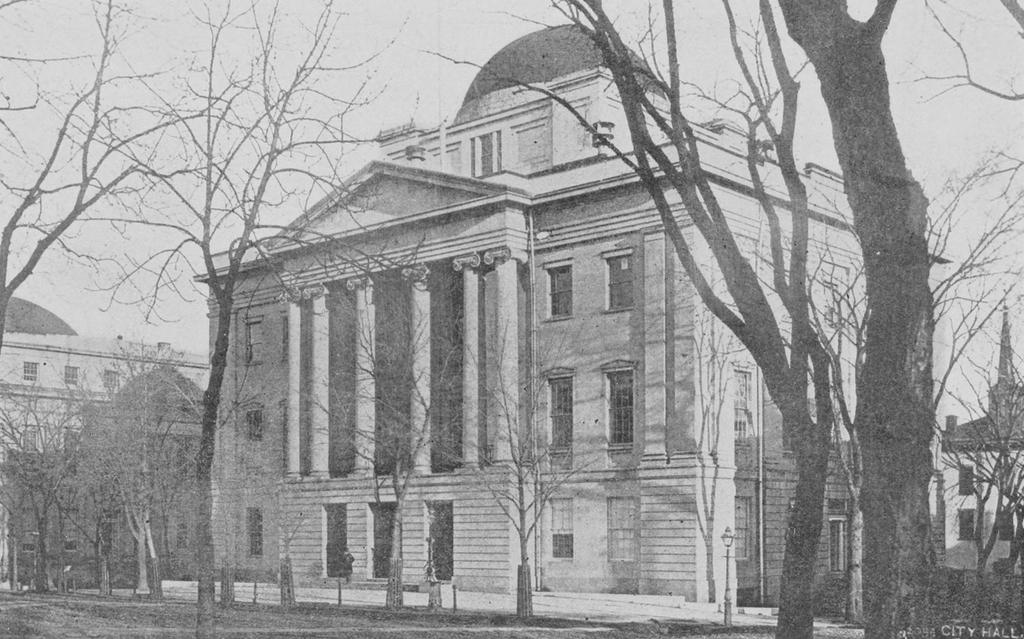

The State House in 2019:

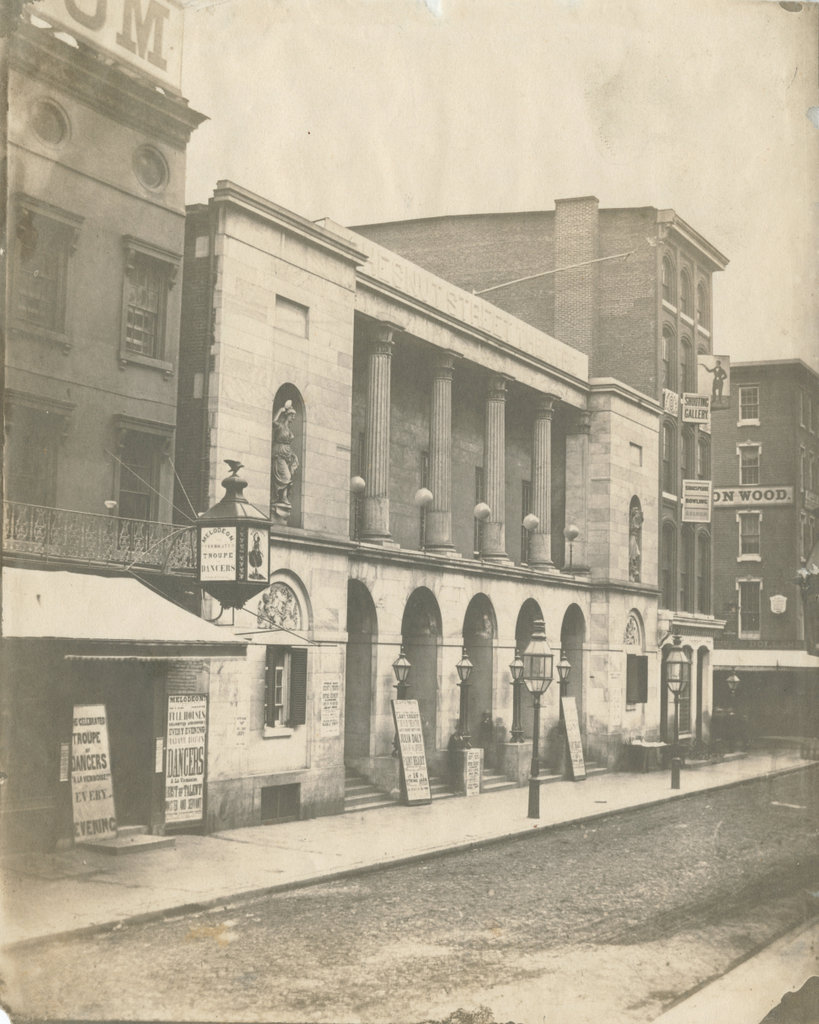

With a population of under 7,500, Montpelier is the smallest state capital in the United States, but it has served as the seat of the Vermont state government since 1805. Up until that point, the state had no formally designated capital, so legislative sessions were held in a variety of locations, including at least 13 different towns over the years. The government finally found a permanent home here, and in 1808 the first state house was completed in Montpelier. It was used for the next 30 years, but in 1838 it was replaced by a new, more substantial capitol. Designed by noted architect Ammi B. Young, it featured a granite exterior with a Doric portico, and it was topped by a low, rounded dome.

This second state house stood here until January 6, 1857, when it was destroyed in a fire that had originated in the building’s heating system. By the time it was discovered, the fire had already spread throughout much of the building underneath the floors, and firefighting efforts were further hampered by the below-zero temperatures, which froze water before it could even reach the fire. Many of the books in the state library, along with a number of other important documents were saved, as was a large portrait of George Washington. However, the building itself was completely gutted, leaving only the granite walls and portico still standing by the time the flames were extinguished.

In the aftermath, there was talk of moving the capital elsewhere. The citizens of Burlington wasted no time in throwing their hat in the ring, and within two weeks they had selected a location for a new state house and had pledged $70,000 towards its construction. Ultimately, though, the state legislature chose to remain in Montpelier, and the state house was reconstructed around the surviving walls and portico of the old building. The architect for this project, Thomas Silloway, retained the same basic appearance of the State House, although he expanded it with an extra window bay on either side of the building, along with a larger dome above it. The dome was topped by a gilded wood statue of Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture, which was designed by noted Vermont sculptor Larkin Mead.

The new State House was constructed at a cost of $150,000, or about $4.4 million today, and it was completed in the fall of 1859. The beginning of Governor Hiland Hall’s second term coincided with the opening of the building, and he acknowledged the occasion in his inaugural address on October 14:

We meet also for the first time in the new State edifice, and can hardly fail to be favorably and agreeably impressed with its fine proportions and the beautiful style of its finish, and also with the convenience of its arrangements, and the appropriate fitness of its furniture and appendages. The building is indeed a noble and imposing structure, and we may justly be proud of it as our State Capitol. I congratulate you on its completion, and I doubt not you will concur with me that much credit is due to those who have been concerned in its erection, as well for the rapidity with which the work has been pushed forward, as for the neat and substantial manner in which it appears to have been executed.

Upon completion, the first floor of the building housed a mix of offices and committee rooms, along with exhibition space for a natural history collection. The second floor housed the Senate chamber in the east wing, on the right side of the building in this scene, with the House of Representatives chamber in the center beneath the dome, and the governor’s office in the west wing on the left side of the building. The library was also located on the second floor, as were offices for state officials such as the clerk of the house, secretary to the governor, and secretary of state.

The first photo was taken a little under 50 years after the building was completed. By this point, it had been expanded several times, with additions to the rear in 1888 and 1900, as shown in the distance on the left side. Another addition would eventually be constructed in 1987, but overall this view of the state house has hardly changed in more than a century since the first photo was taken. Aside from the dome, which was gilded in the early 20th century, and the statue atop it, which was replaced in the 1930s and again in 2018, the state house has had few exterior alterations. The interior has also remained well-preserved, including both legislative chambers, and the building remains in use as the seat of the Vermont state government.