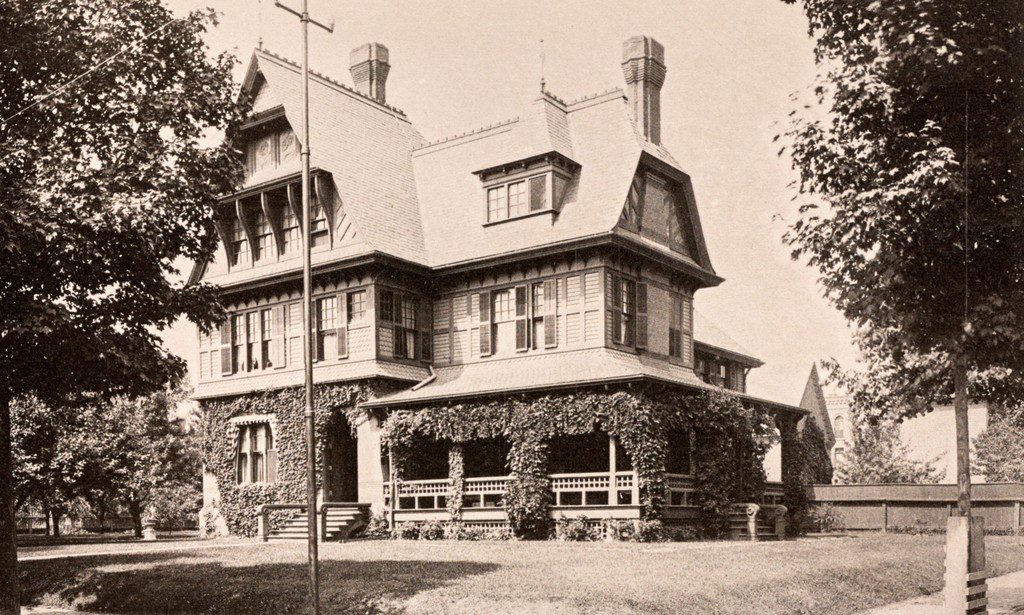

The house at 181 Elm Street, at the corner of Appleton Street in Holyoke, around 1891. Image from Holyoke Illustrated (1891).

The house in 2017:

This elegant Queen Anne-style house was built around 1880, and was originally the home of Clemens Herschel (1842-1930), a prominent hydraulic engineer who worked for the Holyoke Water Power Company. Born in Austria in 1842, Herschel immigrated to the United States as a child, and subsequently graduated from Harvard in 1860. After spending the early part of his career designing bridges and working on the sewer system in Boston, he came to Holyoke in 1879. By the following year’s census, he was living here in this house along with his wife Grace and their two sons, Arthur and M. Winston Herschel.

During the decade that he worked for the Holyoke Water Power Company, Herschel invented the Venturi meter, which was the first effective way of measuring water flow. The meter was in commercial use by 1889, allowing the Holyoke Water Power Company to measure the water use of the individual factories in the city. That same year, Herschel left Holyoke for New Jersey, where he worked as the chief engineer of the East Jersey Water Company from 1889 to 1900. He later served as a consulting engineer for major water projects in New York, including the hydroelectric power plant at Niagara Falls, and in 1915 he became president of the American Society of Civil Engineers. Along with this, Herschel wrote several books, including Frontinus and the Water Supply of the City of Rome, which was a translation of the works of ancient Roman civil engineer Sextus Julius Frontinus.

Although he lived in Holyoke until 1889, Herschel only lived in this house until about 1885, before moving to a house at 209 Linden Street. By 1886, this house on Elm Street was the home of Edward W. Chapin (1840-1924), a prominent attorney and judge. Although originally from Chicopee, Chapin came to Holyoke in 1865 to practice law, and in 1877 he was appointed as a justice of the Holyoke district court. He was later appointed as a judge of the police court in 1898, and served in that capacity until 1919. In addition, he held several other political offices, including serving in the state legislature, on the Holyoke city council, on the school board, and as the city solicitor.

During Chapin’s time in Holyoke in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the city was at the peak of its prosperity as a major manufacturing center. From 1894 until his death in 1924, he was the president of the Farr Alpaca Company, which was the largest textile mill in the city at the time, and he was also a director and vice president of the Mechanics Savings Bank and a director of the Holyoke and Westfield Railroad. Outside of his commercial interests, Chapin was also a director of the Holyoke Public Library and the Holyoke City Hospital, and he also served as president of the board of trustees of Mount Holyoke College from 1906 to 1912.

Edward Chapin and his wife, Mary Beebe, had four children: Arthur, Ann, Alice, and Clara. In 1892, Ann married William F. Whiting (1864-1936), the son of the wealthy paper manufacturer William Whiting, who lived across the street from this house. Arthur continued to live here in his parents’ house until 1897, when he married Tirzah L. Sherwood. A year later, he was elected mayor, and held the office from 1899 until 1904. During their marriage, he and Tirzah lived in a house at 211 Oak Street, but she died in 1901, and by 1903 Arthur had returned here to 181 Elm Street. Arthur would later go on to have a successful political and business career, including serving as Treasurer and Receiver-General of Massachusetts from 1905 to 1909, as State Bank Commissioner from 1909 until 1912, and as vice president of the American Trust Company.

Arthur Chapin remarried in 1907 to Marion S. Murlless, and the 1910 census shows them living here in this house along with his parents and his two unmarried sisters, Alice and Clara. Arthur and Marion moved into their own house by the late 1910s, but Edward and Mary continued to live here on Elm Street for the rest of their lives. He died in 1924, and Mary died four years later, and by the 1930 census their two daughters were living here alone except for a live-in cook.

Alice Chapin died in 1944, at the age of 69, but Clara continued to live here in this house until her death in 1962 at the age of 84, more than 75 years after she moved into the house with her parents and siblings. Since then, the exterior of the house has remained well-preserved. From this angle, the only significant change is the loss of the front porch, but otherwise it retains all of its Queen Anne-style ornamentation, and it survives as an excellent example of Holyoke’s historic 19th century mansions. The property is now owned by the Valley Opportunity Council, and provides low-income housing for veterans.