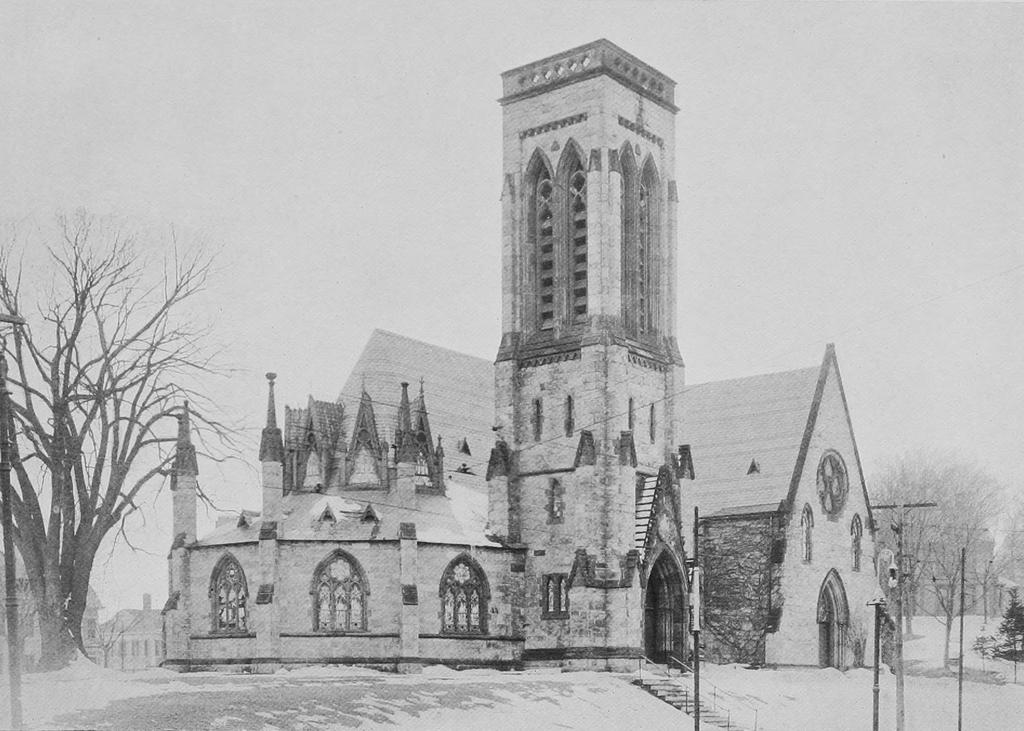

The old post office building, at the corner of Dwight and Taylor Streets in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The building in 2018:

For most of the 19th century, Springfield did not have a dedicated post office building. Instead, it was often housed inside of a store that was run by the postmaster, so over the years the post office had ten different locations before the first purpose-built post office was completed in 1891, at the corner of Main and Worthington Streets. This imposing Romanesque-style brownstone building functioned as both a post office and a customs house, but it soon proved to be too small, as Springfield’s population continued its dramatic growth into the early 20th century. As a result, this post office lasted barely 30 years before it was closed in 1932 and demolished the following year.

Its replacement was constructed several blocks away, on a lot that is bounded by Lyman, Dwight, Taylor, and Kaynor Streets. The latter was added to the city’s street network when the new post office was built, in order to provide access to the rear of the building. It was named in honor of the late W. Kirk Kaynor, a congressman and former Springfield postmaster who was killed in a plane crash in 1929.

The new building opened in September 1932, and it is shown here in the first photo only a few years later. it was primarily a post office, but it also housed a variety of other federal offices. A May 8, 1932 article in the Springfield Republican, published several months before it opened, outlined the intended use of the building. The post office would occupy much of the basement, all of the first floor, and most of the second floor. The rest of the second floor would be used by the customs appraiser, and the third floor would house the federal courtroom, judge’s chambers, district attorney’s office, and other Department of Justice offices. The allocation of space in the fourth and fifth floors was still tentative at the time, but these floors were intended to house a variety of other federal offices.

Architecturally, the building is very different from the previous post office. By the 1930s, the Romanesque architecture of the late 19th century had long since fallen out of fashion, and this new building featured the simplicity of Art Moderne architecture, with a light-colored exterior of polished Indiana limestone. However, it was built with some decorative elements, including the colored terra cotta spandrels in between the windows. Like many Depression-era post offices, it also included interior murals in the main lobby. The ones here were painted by Umberto Romano, and they consist of six murals that are collectively titled “Three Centuries of New England History.”

This building was used as a post office until 1967, when the present post office building opened a few blocks to the north of here. The rest of the federal offices were relocated in 1980, upon the completion of a new federal building at Main Street, and this property was sold to the state three years later. Since then, it has served as the Springfield State Office Building, housing a variety of state agencies, along with the Western Massachusetts office of the governor. Its exterior has remained well-preserved since then, with few noticeable changes from the first photo, and it stands as an excellent example of 20th century architecture in Springfield.