The view looking south toward Crawford Notch in New Hampshire, as painted by Thomas Cole in 1839. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

The scene in 1841, photographed by Dr. Samuel A. Bemis. Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

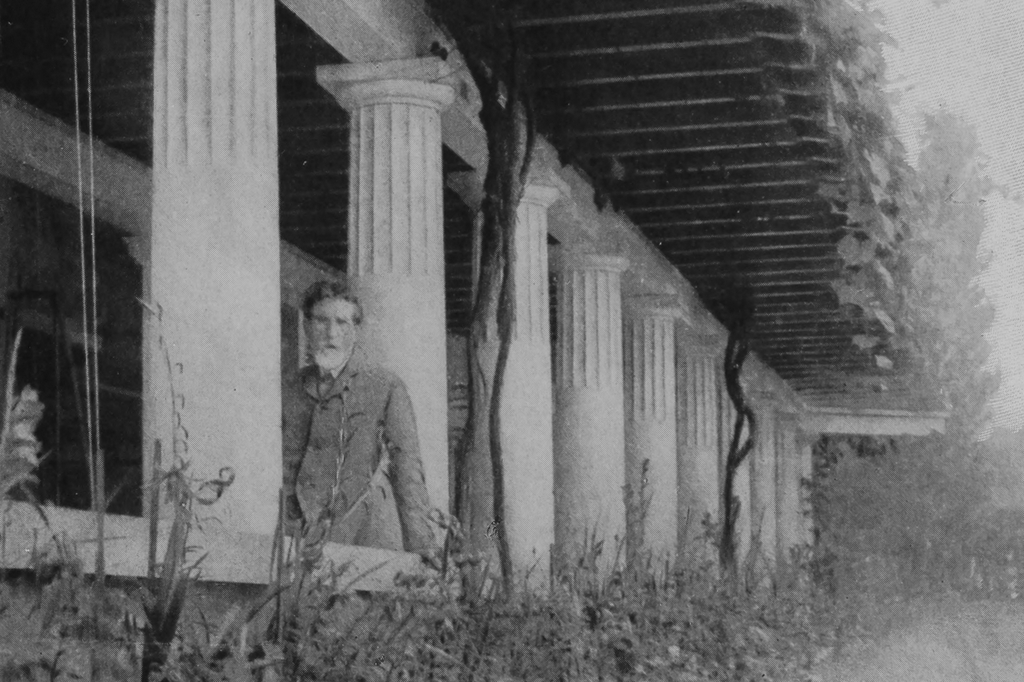

The scene around 1890-1901. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2020:

This view is similar to the one in the previous post, although this one is a little further to the south, showing a closer view of the dramatic gap in the mountains at Crawford Notch. It is a view that has long captivated artists and photographers, as shown by the many different images here. This particular angle looks south through what are known as the gates of Crawford Notch, the narrowest point in the mountain pass. Barely 20 feet wide when discovered by European colonists in 1771, it has subsequently been widened to accommodate road and rail traffic, but it still retains much of the same appearance, with the steep cliffs on either side and the slopes of Mount Webster looming in the background. On the left side of the notch is an exposed rock formation known as Elephant Head, due to its somewhat vague resemblance to the head and upper trunk of an elephant.

The first image here is a painting of Crawford Notch by prominent landscape artist Thomas Cole. He is generally regarded as the founder of the Hudson River School, an artistic movement that emphasized the natural beauty of the American landscape. Cole typically used his artwork to convey the power of nature, and this painting features several of his common motifs, including gnarled trees, ominous storm clouds, and a small human figure that is barely noticeable amid the surrounding landscape. Perhaps the most foreboding element is the dense fog in the valley beyond the notch, giving a sense that the notch is a sort of passage to another world.

Thomas Cole made several visits to the White Mountains, including one in the summer of 1839, accompanied by fellow artist Asher Durand. While here, he sketched this view of Crawford Notch, and he painted this painting after returning to his home in Catskill, New York. Titled A View of the Mountain Pass Called the Notch of the White Mountains (Crawford Notch), it was commissioned by Rufus L. Lord, who paid Cole $500 for the finished work. It is now regarded as one of Cole’s finest American landscapes, and it is currently on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

The second image here is a daguerreotype taken in 1841, just two years after Cole’s visit. It is the oldest photograph that I have featured on this blog, and among the earliest photographs to be taken in the United States, just a few years after Louis Daguerre invented the daguerreotype process. The photographer was Dr. Samuel A. Bemis, a Boston dentist who became one of the first photographer in the country. He began taking photographs in 1840, but evidently abandoned the hobby around 1843, leaving behind a relatively small number of photographs, most of which are poorly exposed. However, his works include the earliest photographic images of the White Mountains, many of which were taken in and around Crawford Notch.

This particular photograph shows nearly the same scene that Thomas Cole had painted two years earlier, although Bemis was a little closer to the notch than Cole was when he sketched the view. On the left side is the Notch House, which appears to be the same building shown in the distance on the left side of the painting. This inn was built in 1828 by Ethan Allen Crawford, and it was operated by his brother Thomas. From here, visitors could ascend to the summit of Mount Washington by way of the 8.5-mile Crawford Path, which Ethan Allen Crawford and his father Abel had cut in 1819.

In 1845, a few years after the photo was taken, the Notch House was expanded with a new addition. The attic was also converted into rooms, giving the inn a capacity of 75 guests. Then, around 1850 Thomas Crawford decided to build a new hotel nearby, just a little to the north of here. However, he ran into financial trouble and ended up having to sell the partially-completed hotel in December 1850. The hotel was finished under the new ownership, and it was named the Crawford House, with Joseph L. Gibbs as its manager. With this new, modern hotel nearby, the old Notch House quickly faded into obscurity. It was used occasionally for overflow accommodations, but it was ultimately destroyed by a fire in June 1854.

The Crawford House ultimately suffered a similar fate when it burned in 1859, but it was quickly rebuilt on the same site and stood there for well over a century, until it too was destroyed by fire in 1977. By the time the third image was taken of Crawford Notch in the 1890s, it was a popular resort destination. The hotel was located about a quarter mile behind where this photo was taken, so it is not visible in this scene, but there are other signs of changes here in the 1890s photo, particularly the railroad. In the 1841 image, the Notch House would have been accessible only by stagecoach, but in 1875 the Portland & Ogdensburg Railroad opened through the notch, making it much easier for tourists to visit the area.

Today, nearly two centuries after Thomas Cole painted Crawford Notch, the foreground of this scene has undergone substantial changes. Cole himself hinted at some of these impending changes with the cleared ground and tree stumps, but he probably did not anticipate that a railroad would one day be built through here, or that the rough stagecoach road would eventually become the modern US Route 302. However, despite these changes, the surrounding landscape has remained nearly unchanged. Cole did embellish parts of the scene, including the prominence of Mount Webster and the narrowness of the notch, but overall the landscape is still instantly recognizable from the painting, and Crawford Notch remains one of the most impressive natural features in the White Mountains.