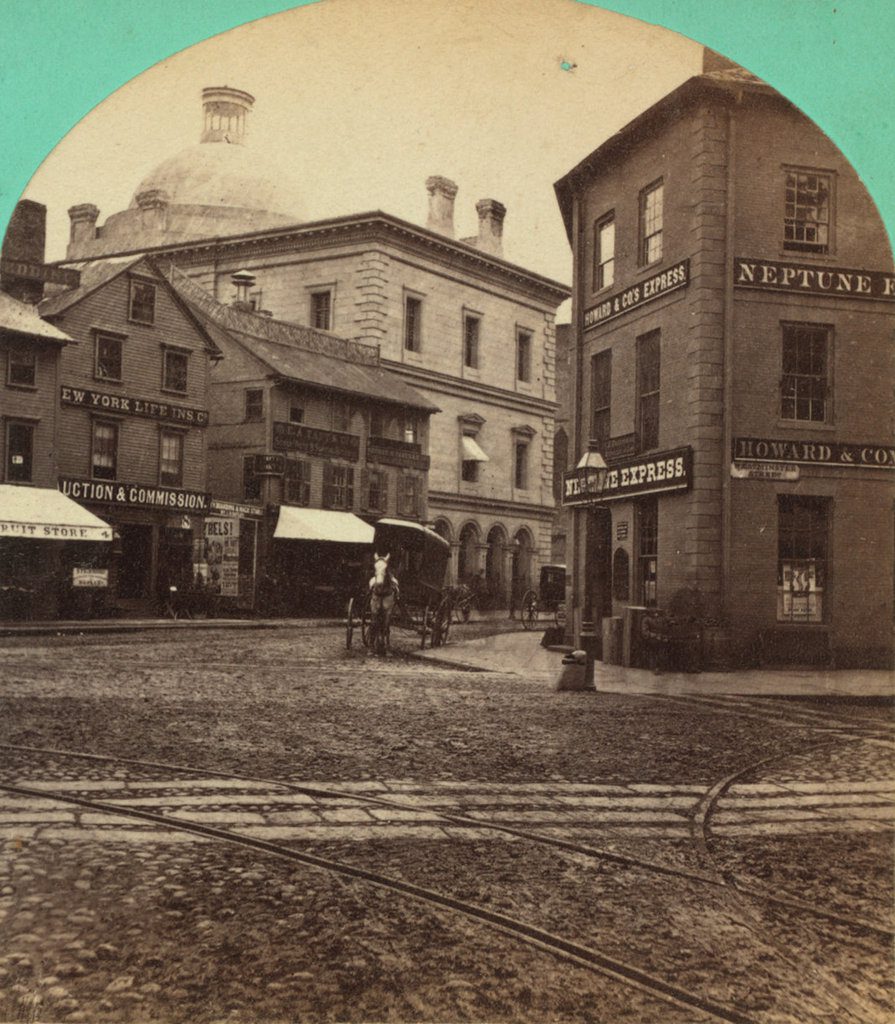

The Warner House hotel on Main Street in Northampton, sometime around the 1860s. Image from Northampton: The Meadow City (1894).

The scene in 2017:

The Warner House, seen on the left side of the first photo, had been perhaps the most prominent hotel in early 19th century Northampton. The wooden, three-story Federal-style building dated back to the 1790s, when it was built by Asahel Pomeroy, who operated it as a tavern. It was ideally located in the center of Northampton, where several major stagecoach routes crossed, including an east-west route from Boston to Albany, and a north-south route from New Haven and Hartford to Brattleboro and other points north.

In 1821, the tavern was purchased by Oliver Warner, and it continued to serve as both a stagecoach stop as well as a popular gathering place for locals. Probably its most famous visitor during this time was the Marquis de Lafayette, who stayed here in 1825 during his grand tour of the United States. The Revolutionary War hero arrived in Northampton to much fanfare, and attended a reception and dinner in his honor here at the Warner House. He later gave a speech from the balcony, and spent several days in Northampton before continuing on his journey east.

Another 1820s visitor was Prince Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, a German prince who had fought for the Netherlands in the Seven Years’ War a decade earlier. He later published an account of his 1825-1826 visit to the United States, which included a stop here at the Warner House. In the English translation of the book, he gives a detailed description of both the hotel and Northampton itself:

About a mile from Northampton we passed the Connecticut river, five hundred yards wide, in a small ferry-boat, which, as the night had already set in, was not very agreeable. At Northampton we took lodgings at Warner’s Hotel, a large, clean, and convenient inn. In front of the house is a large porch, and in the first story a large balcony. The gentlemen sit below, and the ladies walk above. Elm trees stand in front of the house, and a large reflecting lamp illuminates the house and the yard. This, with the beautiful warm evening, and the great number of people, who reposed on the piazza, or went to and from the house, produced a very agreeable effect. The people here are exceedingly religious, and, besides going to church on Sundays, they go thrice during the week. When we arrived, the service had just ended, and we saw some very handsome ladies come out of the church. Each bed-chamber of our tavern was provided with a bible.

By the middle of the 19th century, railroads had supplanted stagecoaches as the primary means of intercity transportation, but the Warner House continued to be one of Northampton’s leading hotels. It was one of three Northampton hotels listed in the 1851 The Mt. Holyoke Hand-book and Tourist’s Guide; for Northampton, and its Vicinity, which wrote that:

Warner’s Hotel is in the centre of the town, and in the midst of the trading part of the community. The house was inadequate in size to its business, and a large and very handsome addition has just been made to it, the rooms of which are spacious, airy and pleasant. The venerable proprietor has made a spirited and liberal outlay, by which he has added much to the beauty of the town, as well as promoted to public convenience; and we trust he will receive that ample remuneration he so well deserves.

This “handsome addition” was likely the three-story brick building on the right side of the photo, which was built in the prevailing Italianate style of architecture, in sharp contrast to the 18th century tavern building. With this expansion, the hotel remained in business for the next two decades. However, the 1870s saw several disastrous fires in downtown Northampton, including one that started here in the Warner House. The fire burned for four hours, destroying the old hotel building, the newer brick addition to the right, and the Lyman Block on the left, and it caused about $125,000 in damage.

In the wake of the fire, the site was rebuilt as the Fitch House, a large four-story brick, Italianate-style hotel building that was completed in 1871. The hotel was later named the Mansion House, and then the Draper Hotel,and it remained in business until it finally closed in 1955. The eastern two thirds of the Draper Hotel was subsequently demolished, and the current one-story building was built in its place, but the westernmost section of the building is still standing, and can be seen on the left side of the present-day photo.