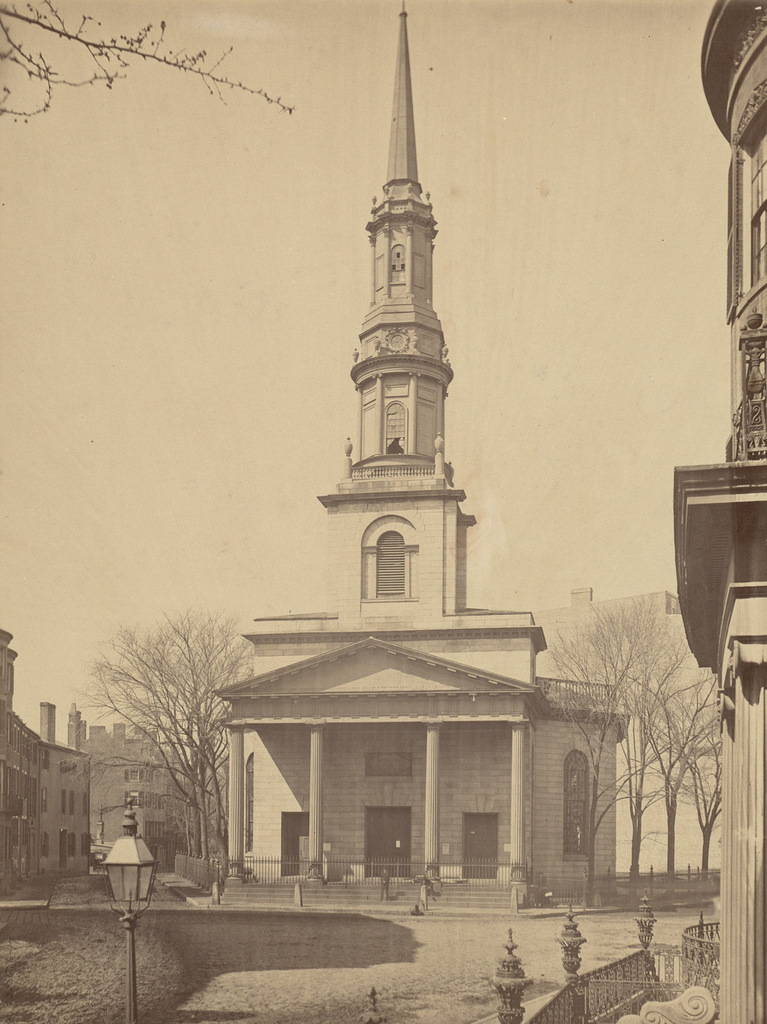

New South Church at the corner of Summer and Bedford Streets in Boston, around 1855-1868. Image courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

The scene in 2015:

Not to be confused with the Old South Meeting House, or the New Old South Church, this church at the corner of Summer and Bedford Streets was known as the New South Church. It was octagonal in shape and made of granite, and it was designed by Charles Bulfinch, a prominent early American architect who designed a number of buildings in Boston, including the Massachusetts State House, the expanded Faneuil Hall, and Boylston Market.

When the church was completed in 1814, this neighborhood in the present-day financial district was an upscale residential area. A few block away on Franklin Street was Bulfinch’s famous Tontine Crescent, and here on Summer Street there were also a number of high-end townhouses. Daniel Webster lived in a house at the corner of Summer and High Street, just a few steps back from where these photos were taken, and although he died before the first photo was taken, this would have essentially been the view he would have seen whenever he left his house.

By the 1860s, though, Boston was running out of land, and this area was eyed for redevelopment. Most of the townhouses were taken down as the neighborhood shifted from residential to commercial, and in 1868 the New South Church was also demolished and replaced with a bank. The new building didn’t last long, though; it was destroyed in the Great Boston Fire of 1872, and the present-day Church Green Building was completed the following year. Although the historic church is long gone, its eventual replacement has become historic in its own right. Despite being in the heart of the Financial District, it has survived for nearly 150 years, and it is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.