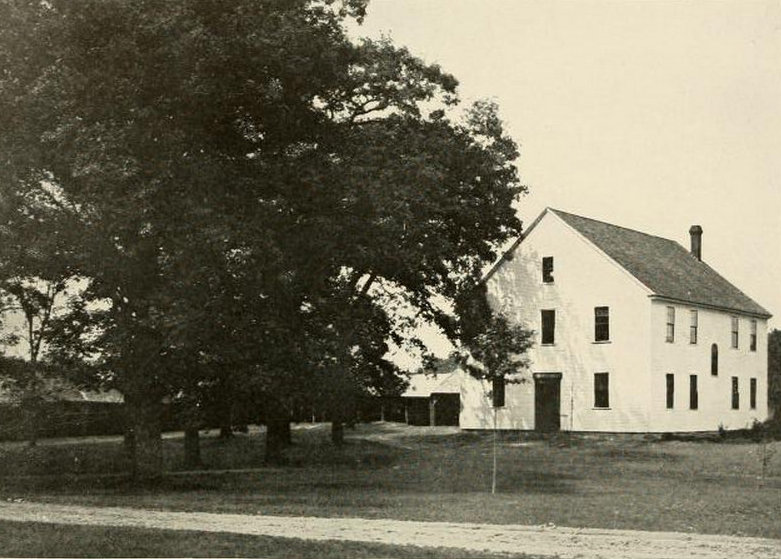

The First Meetinghouse building on Church Street in Ludlow, around 1912. Image from The History of Ludlow, Massachusetts (1912).

The building in 2025:

Built in 1783, this is one of the oldest church buildings in the Connecticut River Valley, although it hasn’t functioned as a church in over 170 years. It doesn’t look much like a church, but it actually hasn’t changed much in exterior appearance over the years. The white, steepled churches that we commonly associate with New England towns were not yet universally adopted in the late 1700s. Particularly in small towns, simple structures like this were still common, as seen in other places like Rockingham Vermont, where a similar-looking meeting house was built around the same time.

A steeple wasn’t the only thing that many of these early meeting houses lacked, though – another one was heat. Some, like the one in Rockingham, still don’t have heat over 225 years later. However, here in Ludlow a stove was finally installed in 1826. Fifteen years later, a new church was built, and the old one was sold to Increase Sikes for the princely sum of $50 and moved across Church Street to its present location; it had previously been in what is now the triangle of land between Church Street and Center Street. Sikes soon sold it back to the town, and it was used for town meetings until 1893, when the town offices were moved to the rapidly-growing industrial village along the Chicopee River in the southwest corner of town.

For many years, the building was used as a Grange Hall, until the town purchased it again in 2000. Since then, the building has been restored, and it forms an important part of the Ludlow Center Historic District, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.