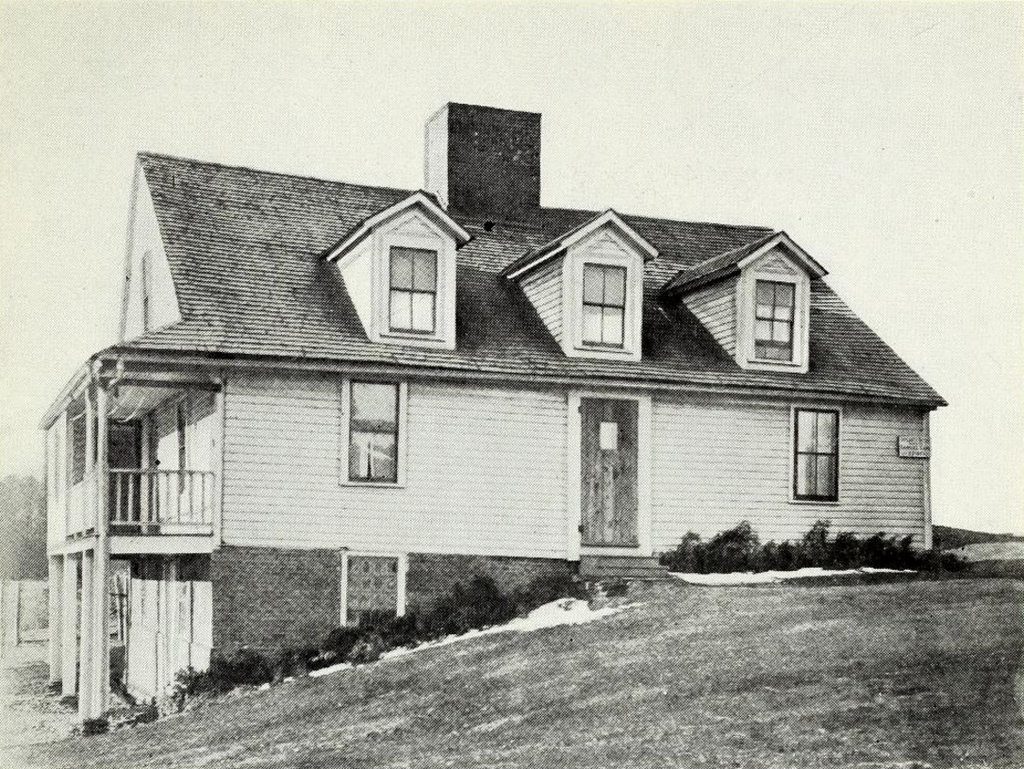

The house at 1007 Halliday Avenue West in Suffield, around 1921. Image from Celebration of the Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Settlement of Suffield, Connecticut (1921).

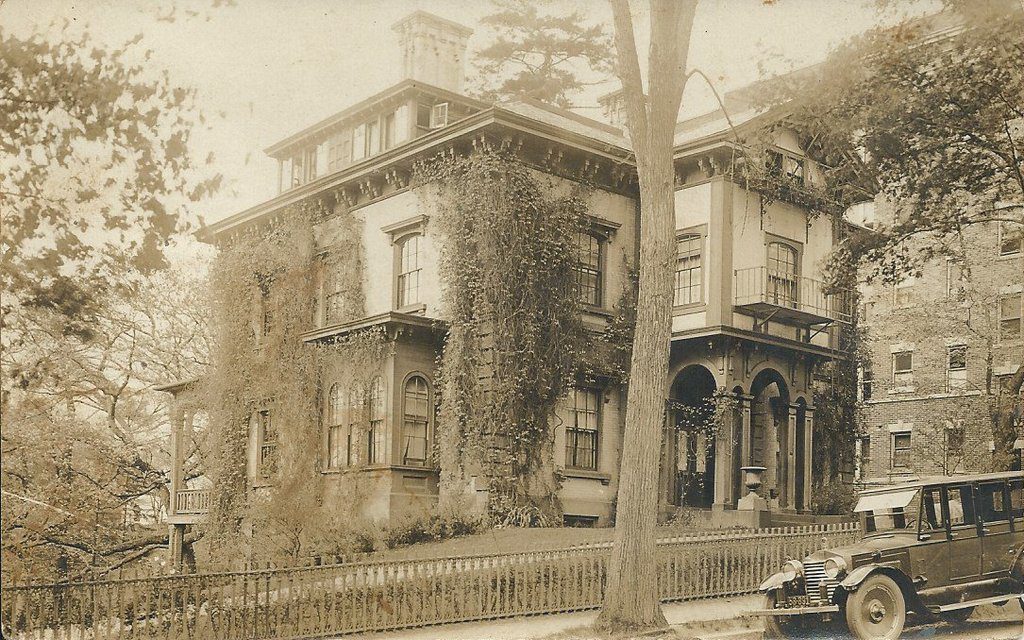

The house in 2017:

Different sources identify this house as having been built in 1726, 1740, or 1744, but either way it is one of the oldest houses in Suffield, and was originally owned by Samuel Lane. Born in Hadley, Massachusetts, Samuel later moved to Suffield, where he married Abigail Hovey in 1709. In 1723, he purchased 23 acres of land here in the northern part of the town, and subsequently built this house at some point over the next two decades. At the time, Suffield was part of Massachusetts, but was part of a border dispute that was eventually resolved in 1749, when the two colonies established the present-day border, about a third of a mile north of Samuel’s house.

Samuel owned this house until 1765 when, a few years before his death, he transferred the property to his grandson, Gad. About 21 years old at the time, Gad’s father Samuel had died in 1748 when Gad was just a few years old. But, as the oldest son of Samuel and Abigail’s oldest son, he inherited the family home, along with 40 acres of land. The house was situated on the main road from Suffield to Westfield, Massachusetts, and for some time Gad operated a tavern in the walk-in basement on the left side of the house. Here, 18th century cattle and sheep drivers could satiate their hunger and thirst at the tavern, while their herds and flocks did the same in the surrounding pastures and at the stream that flows just to the left of the house.

In 1772, Gad married the curiously-named Olive Tree, and the couple had five children: Hosea, Gad, Comfort, Ashbel, and Zebina. However, in 1798 Gad filed for divorce, alleging that Olive had run off with another man and had stolen many of his possessions. A March 19, 1798 notice, published in the Hartford Courant, provides the details of her infidelity, with Gad stating that: “Olive formed an improper connection with one Joſeph Freeman: That ſhe has frequently and privately took and conveyed to ſaid Freeman, the petitioners bonds, obligations, papers, cloathing and other property: That ſaid Olive hath committed adultery with ſaid Freeman — hath eloped from the petitioner and now lives in a ſtate of adultery with ſaid Freeman.”

Gad subsequently remarried to Margaret Ferry, and in 1827 he gave the property to his son Ashbel. He owned the house for 20 years before selling it in 1847, and after changing hands several times the property was purchased by David Allen in 1849. He and his wife Mary went on to live here for nearly 40 years, running a modest farm that, during the 1880 census, consisted of eight acres of tilled land, plus six acres of meadows and orchards, and four acres of woodland. His primary crops were corn, oats, rye, potatoes, and apples, and his property had a total value of $2,500, plus $100 in farm machinery and $150 in livestock.

The Allen family would remain here until 1888, when David sold the property a few years before he and Mary died. The property changed hands several times over the next few decades, and by the time the first photo was taken the house had been significantly altered, including the addition of three dormers. Well into the 20th century, the house lacked modern conveniences such as heat and bathrooms, and by the late 1930s it was owned by Raymond Kent, Sr., a tobacco farmer who used the house as a residence for his field hands. However, in 1942 his son, Raymond Kent, Jr., restored the house, and today it still stands well-preserved as one of the oldest surviving houses in Suffield.