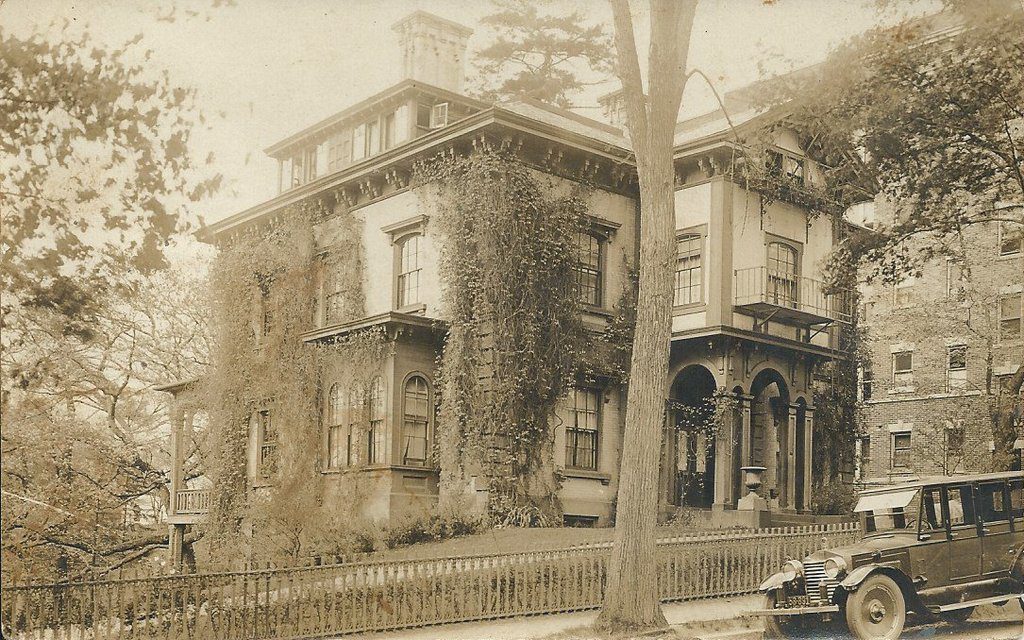

The house at 182 Central Street in Springfield, probably sometime around 1910-1920. Image courtesy of Jim Boone.

The house in 2017:

This elegant Italianate-style home was built in 1853, along the slope of Ames Hill near the corner of Maple and Central Streets. It was designed by Henry A. Sykes, an architect from Suffield, Connecticut, whose other Springfield works included the Mills-Stebbins Villa on nearby Crescent Hill, and it was originally owned by Francis Tiffany, the pastor of the Church of the Unity. Reverend Tiffany had become the pastor of the church in 1852, and he would go on to serve the congregation for the next 12 years. He and his wife Esther lived in this house throughout this time, and by the 1860 census they were living here with four young children.

In 1864, Tiffany left the church to take a position as an English professor at Antioch College in Ohio, and he sold the house to Samuel Bowles, who was a friend of his and one of the most influential men in the city. He was the son of Samuel Bowles II, a journalist who had founded the Springfield Republican as a weekly newspaper in 1824. The younger Samuel was born two years after the paper started, and began working alongside his father when he was 17. Around the same time, the Republican became a daily newspaper, and after his father’s death in 1851, Samuel took over control of the paper, when he was just 25 years old.

By the time Samuel Bowles and his wife Mary moved into this house, the Republican was one of New England’s leading newspapers, and as the name of the paper suggested, it generally supported Republican, anti-slavery policies before and during the Civil War. Bowles was also a friend of Emily Dickinson, and he published several of her poems in the Republican. These poems, which were heavily edited in order to conform with conventional poetic styles, were among the very few that were ever published during her lifetime, as most of her nearly 1,8000 poems were discovered and published posthumously.

Samuel and Mary Bowles raised ten children in this house, although during this time he frequently traveled. He suffered from poor health, which was attributed to over-working, so because of this he took a number of trips to the American West and to Europe in the 1860s and early 1870s, often publishing accounts of his travels. However, he died in 1878, at the age of 51, and the responsibility of running the newspaper fell to his son, Samuel Bowles IV, who was 26 years old at the time, just a year older than his father had been when he took over the paper in 1851.

By the end of the 19th century, the house had become part of the MacDuffie School, which had been founded in 1890 by John and Abby MacDuffie as a school for girls. The Bowles house became the school’s main classroom building, but over time the campus expanded, eventually encompassing many of the historic mansions on and around Ames Hill. The house became part of the Ames/Crescent Hill Historic District when it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974, but in 1978 the school requested permission from the Historical Commission to demolish the house, claiming that it was in poor condition and that the land was needed for tennis courts. The Commission ultimately granted the request, and despite a court challenge by local preservationists, the house was demolished in 1980. However, the tennis courts were never built, and the site of the house remains vacant nearly 40 years later.