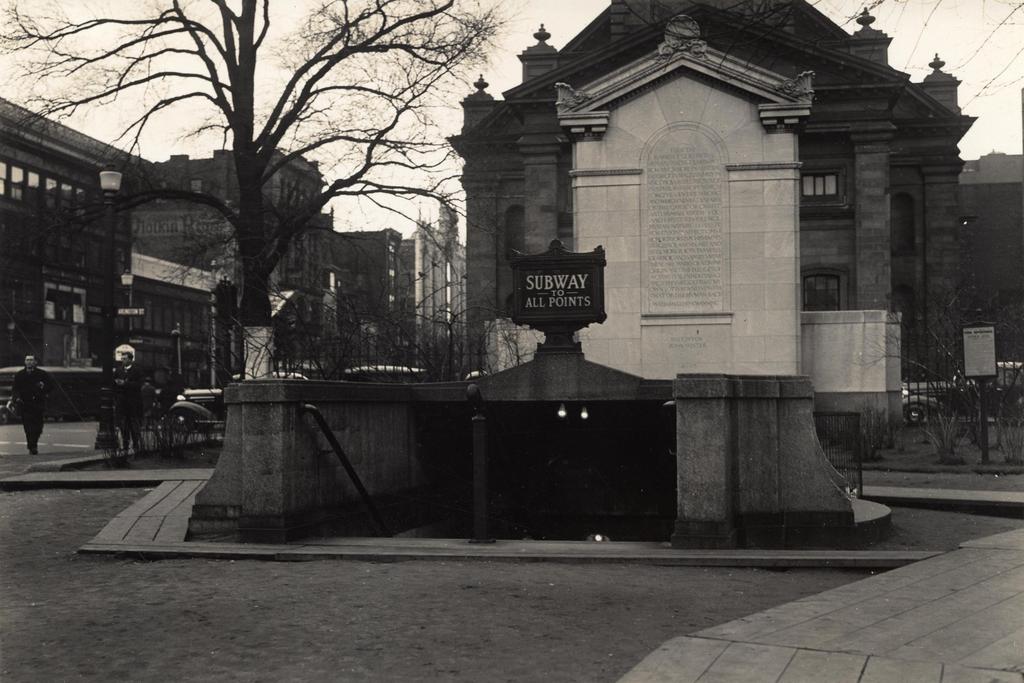

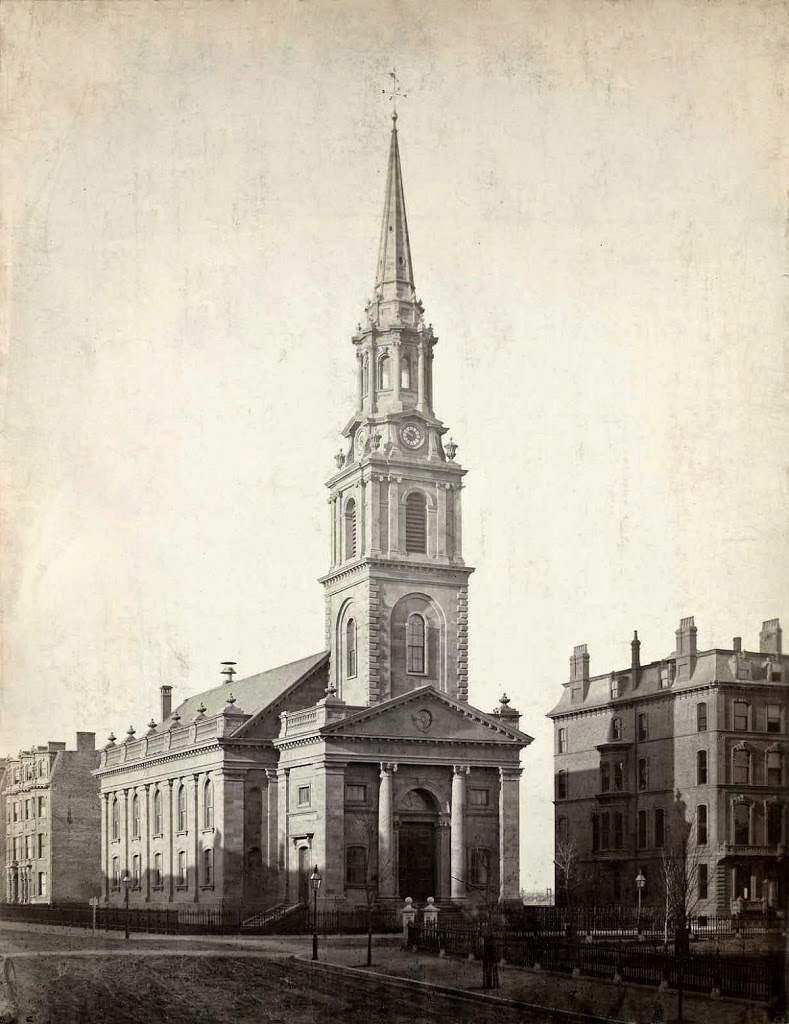

The houses at 1 Commonwealth Avenue and 12 Arlington Street in Boston, sometime in the 1870s. Image courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

The houses in 2017:

This building at the corner of Arlington Street and Commonwealth Avenue was actually built as two separate houses, starting with the house on the right at 12 Arlington Street. Located on the sunny north side of Commonwealth Avenue and directly opposite the Public Garden, this house occupies one of the most desirable locations in the entire Back Bay neighborhood. Completed in 1860, it was also among the first houses to be built in the new neighborhood, with the development starting here at the Public Garden and steadily working westward over the next few decades. It was originally owned by John D. Bates, a merchant who had paid $13,695 for the vacant lot in 1858, and subsequently had this elegant house built here.

In the meantime, the slightly smaller lot at 1 Commonwealth was purchased by Samuel Gray Ward, who built his house here around 1861. Ward was a banker who worked as agent for the prominent Baring Brothers of London, and by the time he and his wife Anna moved into this house he was a very wealthy man. Aside from his career in international banking, though, Ward was also involved in the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. Although Transcendentalism is more associated with utopian communes and cabins at Walden Pond, rather than townhouses on Commonwealth Avenue, Ward was good friends with leaders in the movement, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Margaret Fuller. He even had several poems published in the literary magazine The Dial, although that was mostly the extent of career as a writer.

Samuel and Anna Ward ended up living here for just a few years, because in 1865 they moved to New York City, where he went on to become one of the founders of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That same year, the house was sold to Nicholas Reggio, an Italian merchant who lived here for two years until his death in 1867. His widow, Pamelia, was probably still living here when the first photo was taken, but in the late 1870s the house was sold again, to cotton merchant James Amory. He likewise only lived here for a few years before his death, and his family sold the house in 1892.

Like its neighbor, the house at 12 Arlington also changed hands several times in only a short period of time. John Bates died overseas in 1863, and five years later the property was sold to merchant William H. Bordman, who in turn sold it five months later to Nathan Matthews. A real estate developer, Matthews served as the president of the Boston Water Power Company from 1860 to 1870, and in that capacity he was involved in the filling of the Back Bay. He was also a philanthropist, and his contributions included Matthews Hall, a Harvard dormitory that was completed in 1872 and still bears his name today.

Matthews apparently ran into financial trouble, perhaps caused by the Panic of 1873, because in 1876 he sold the house to two of his creditors. The following year, they sold the house to another real estate investor, Joshua Montgomery Sears. Born in 1854, Sears was an orphan by the age of two, but he inherited a sizable fortune from his father, Joshua Sears, who had been a wealthy merchant. This inheritance was held in a trust during his childhood, gaining interest for 20 years, so by the time he graduated from Yale at the age of 22, he was already one of the wealthiest men in Boston, with a fortune purported to be worth $7 million.

In 1877, the same year as his graduation, he married Sarah Choate, a 19-year-old aspiring artist whose father, Charles F. Choate, was the president of the Old Colony Railroad. Sears purchased this house for her as a wedding gift, paying Matthews’s creditors the princely sum of $110,000 for the property. The purchase was just for the house at 12 Arlington, but in 1892 he bought the adjoining house at 1 Commonwealth and combined the two homes, removing the Commonwealth Avenue entrance in the process. Along with this, he also owned a country estate in Southborough, the 1,000-acre Wolf Pen Farm.

Joshua Sears went on to have a successful career as a businessman, but it was his wife Sarah who went on to achieve far more lasting fame. A patron of the arts, Sarah commissioned portraits by artists such as John Singer Sargent and Mary Cassatt, and also purchased paintings from leading European artists, including Degas, Manet, Cézanne, and Matisse. However, she was also a successful artist and photographer in her own right, and exhibited her work at many of the major world’s fairs in the 1890s and early 1900s. Joshua died from pancreatic cancer in 1905 at the age of 50, but Sarah outlived him by more than 30 years, and owned this house until her death in 1935.

In the following years, this house was put to a variety of uses. During World War II, it was a club for officers in the Army and Navy, and after the war it was purchased by the Boston Archdiocese and used as a school and convent. In 1966, it was converted into offices, and was eventually owned by Sears, Roebuck & Company (no relation to the building’s former owner). Most recently, in the mid-1990s, the building was converted back into residential use, and it is now divided into nine condominium units.

For more detailed historical information about this house, see the house’s page on the Back Bay Houses website.