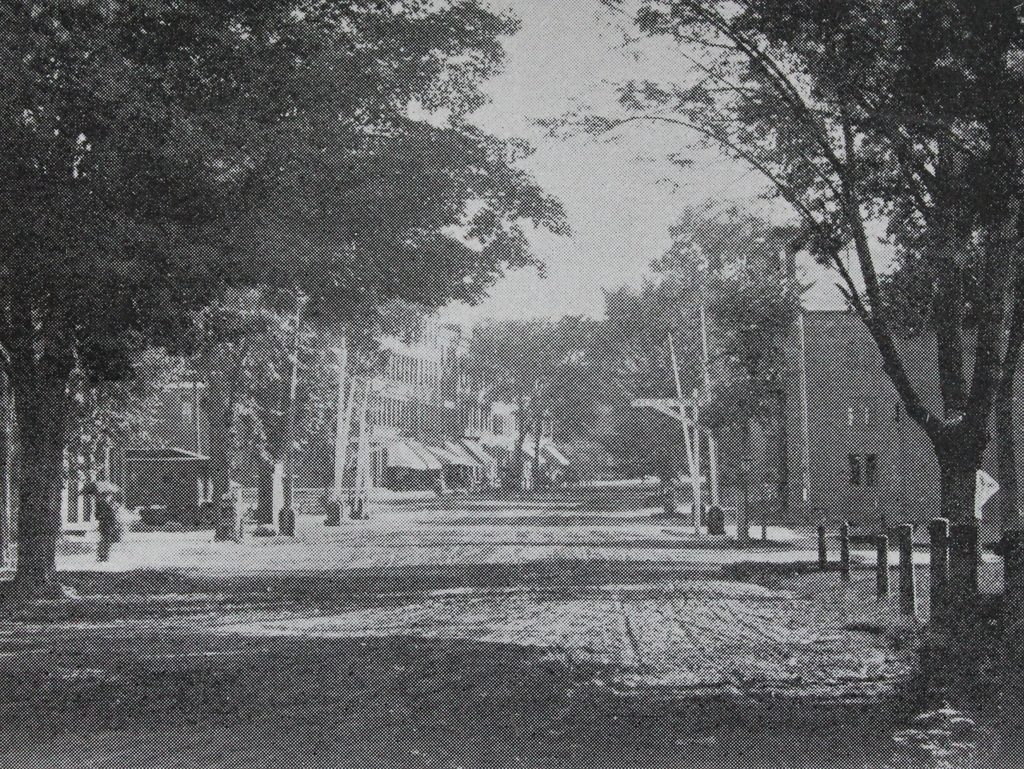

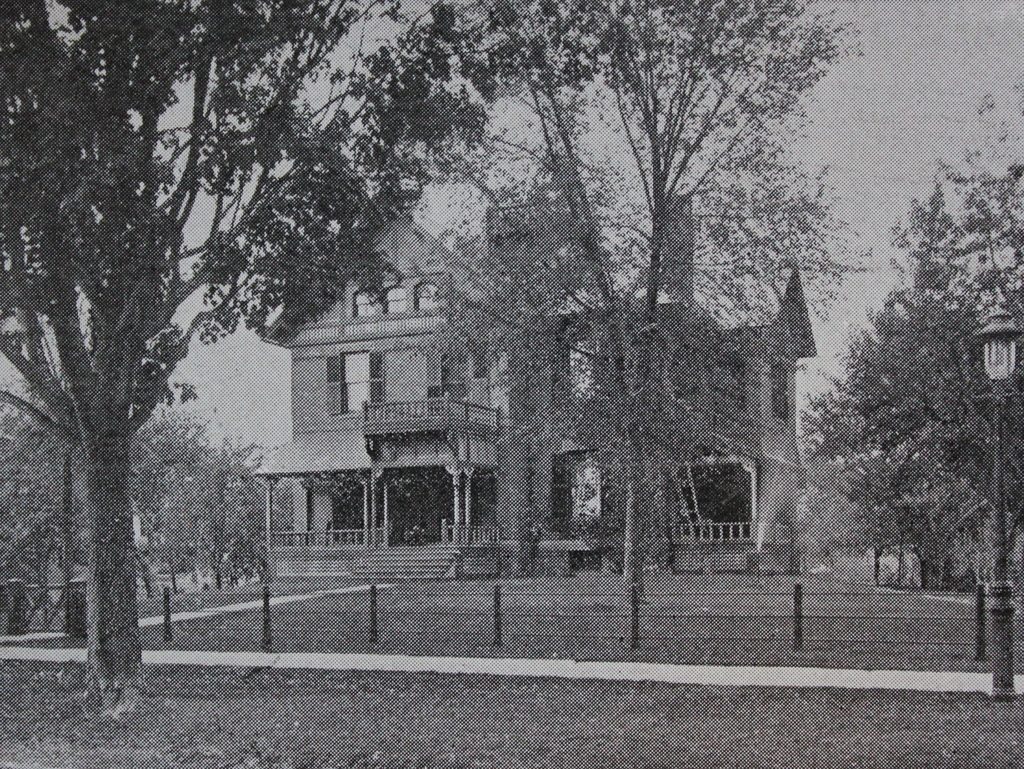

The house at 19-21 Massasoit Street in Northampton, around 1915-1920. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection.

The scene in 2018:

Throughout American history, there have been plenty of presidents who have come from humble beginnings, but few of them lived quite as modestly, both before and after their presidencies, as Calvin Coolidge. He was president throughout most of the Roaring Twenties, yet he had far more in common with his Puritan ancestors than with any characters in an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel. In many ways, he was the archetypal frugal Yankee, and one of the most visible examples of this was his choice of a residence here in Northampton. Rather than owning a home, he spent nearly 25 years renting the left side of this duplex, and it was here that he rose in the political ranks from a state legislator to president of the United States.

This two-family home was built around 1901, in a residential development about a mile to the northwest of downtown Northampton. Most of the other nearby houses were built around the same time, and they were generally single-family homes occupied by middle class residents. Calvin and Grace Coolidge moved in several years later, in August 1906, less than a year after they were married and only a few weeks before the birth of their first child, John. They occupied the left side of the house, at 21 Massasoit Street, for which they paid $27 per month for seven rooms and 2,100 square feet of living space.

Although he spent most of his life in Northampton, Calvin Coolidge was a native of Vermont, where he grew up in the family home in Plymouth. However, he came to Massachusetts for college, attending Amherst College and graduating in 1895. From there, he moved to nearby Northampton, the county seat, and began studying law as an apprentice in the firm of Hammond & Field. He was admitted to the bar in 1897, and soon began practicing law while also getting involved in local politics. He served on the city council, was subsequently appointed city solicitor, and then became Clerk of Courts of Hampshire County, where he worked in the old county courthouse.

Coolidge married his wife Grace in October 1905, when he was 33 and she was 26. Two months later, he suffered the only electoral defeat of his career, when he lost a race for school committee. However, the following year he was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, only a few months after moving here to Massasoit Street. He was reelected to the legislature in 1907, but he declined to run for a third term in 1908. This was motivated in part by the birth of his second son, Calvin Coolidge, Jr., in April of that year. Returning to Northampton meant that he could devote his full attention to his law practice, in order to pay for the added expenses of a second child.

However, Coolidge did not stay out of politics for long. In the fall of 1909, he ran for mayor of Northampton, winning by a margin of just 107 votes. He went on to serve two one-year terms in city hall from 1910 to 1911, where he applied his own personal frugality to the city budget. He reduced the city’s debt while also lowering taxes, yet he also managed to increase teachers’ salaries, improve the roads, and make the police and fire departments more efficient. Coolidge’s cost-saving measures included blocking a proposed new city hall, which would have replaced the old building that had stood since 1850. As it turned out, this proved to be a sensible move, because the old building remains in use as city hall more than a century later.

In 1912, Coolidge returned to the State House, this time as a state senator. This began his meteoric rise in state politics, from mayor of a small city to governor of Massachusetts in just seven years. He served four years in the state senate, including the last two years as senate president, and in the fall of 1915 he became the Republican nominee for lieutenant governor. His running mate, Samuel W. McCall, had narrowly lost the gubernatorial race to David I. Walsh a year earlier, but McCall and Coolidge won in 1915. In an early sign of Coolidge’s popularity, he won the lieutenant governor’s race by over 52,000 votes, while McCall was elected governor by just 6,313 votes.

McCall and Coolidge were successfully reelected in 1916 and 1917. In 1918, McCall announced that he would not run for a fourth term, so Coolidge became the Republican nominee for governor. He defeated his Democratic challenger, businessman Richard H. Long, by over 17,000 votes, and he was inaugurated as governor on January 2, 1919. He would go on to win reelection in the fall of 1919, this time defeating Long by a commanding margin of 125,000 votes.

As was the case here in Northampton, Coolidge’s time as governor was marked by fiscal conservativism. The best example of this came in September 1919, when the Boston Police Department threatened to strike. At the time, the city’s police department was directly controlled by the governor, not the mayor, and Coolidge threatened to fire any striking officers. About three-quarters of the police force went on strike anyway, and Coolidge followed through with his threat, famously declaring, “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anyone, anywhere, any time.” The strike caused a temporary increase in crime and violence in Boston, but the National Guard soon restored order while the city hired and trained new officers.

The police strike earned Coolidge national attention. In the days before the strike, many feared that, if the Boston police offers were successful in their strike, it would inspire similar actions across the country, leading to local governments being essentially extorted by their own police. By taking a hard stance against the strikers, and by emphasizing the need for law and order, Coolidge became a hero to many, and he was seen as a rising star within the Republican Party. The strike also contributed to Coolidge’s overwhelming victory in the 1919 election, earning him more than 60% of the statewide vote.

As a result, Coolidge was viewed as a presidential contender in 1920. Warren Harding was ultimately chosen as the party’s nominee at the Republican National Convention in June, but Coolidge was selected as the vice presidential candidate. It was the first election after the passage of the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote, and both Harding and Coolidge had been supporters of women’s suffrage. Women voted overwhelmingly for the Republican ticket, resulting in a landslide victory for Harding and Coolidge, who carried 37 states and won over 60% of the popular vote.

Upon becoming vice president, Coolidge and his family moved to Washington, where they lived at the Willard Hotel. However, they would maintain this house as their Northampton residence, throughout Coolidge’s time in Washington. His vice presidency was relatively uneventful for nearly two and a half years, but this all changed when Warren Harding died suddenly on August 2, 1923. Coolidge was visiting his father in Vermont at the time, and he was awakened early in the morning and informed that he had become president. The elder Coolidge, who was a justice of the peace, administered the oath of office to his son in the parlor of his house, and then Calvin Coolidge’s first act as president was to go back to bed.

Coolidge easily won reelection in 1924, winning 35 states and 382 electoral votes in a three-way race between Democrat John W. Davis and Progressive Robert M. La Follette. As was the case in Northampton and in Boston, Coolidge sought to cut taxes and lower spending while also reducing the national debt. He held a laissez-faire attitude toward the economy, and his presidency saw widespread growth and prosperity during what came to be known as the Roaring Twenties. However, his economic policies are sometimes criticized for the role that they may have played in the stock market crash of 1929, which occurred less than eight months after he left office.

Coolidge did not run for reelection in 1928, instead endorsing the candidacy of his commerce secretary, Herbert Hoover. He and Grace left the White House in March 1929, and they returned here to their home on Massasoit Street. The 1930 census listed Coolidge’s occupation simply as “retired,” and at the time they were paying $40 per month in rent, equivalent to about $620 today. They lived alone except for one servant, Alice Reckahn, who had been with the family since 1916 and had cared for the house while the Coolidges were in Washington.

It was certainly a modest home for an ex-president, but this did not seem to bother him. In his autobiography, published in 1929, Coolidge explained why he had lived here for so long, writing:

We liked the house where our children came to us and the neighbors who were so kind. When we could have had a more pretentious home we still clung to it. So long as I lived there, I could be independent and serve the public without ever thinking that I could not maintain my position if I lost my office. I always made my living practicing law up to the time I became Governor, without being dependent on any official salary. This left me free to make my own decisions in accordance with what I thought was the public good. We lived where we

did that I might better serve the people.

However, the location of the house proved to be a problem during Coolidge’s retirement. By this point, he was a prominent public figure, and his house offered little privacy from the many curious people who came down Massasoit Street to see the house. Author Claude M. Fuess, in his 1940 biography Calvin Coolidge, The Man From Vermont, provided the following description of the situation:

But Massasoit Street was sought by a continuous procession of sightseers; indeed Dr. Plummer [Frederic W. Plummer, principal of Northampton High School, who had lived in the unit on the right since about 1918], who still occupied the other side of the house, estimated that, in May, an automobile passed on the average every six seconds, and later in the summer the street was sometimes blocked with cars. The Coolidges did their best to lead a normal life. Mrs. Reckahn continued to act as housekeeper, and the flower garden was turned into a runway for the dogs brought from Washington. The ex-President tried to sit on the porch in the evening as he used to do. But whenever he appeared in public a crowd was sure to gather, and the unceasing demonstrations of popularity wore on his nerves. The house was altogether too near the street, and he soon found his conspicuous position highly distasteful.

As a result, in 1930 the Coolidges purchased a house at 16 Hampton Terrace, located just to the south of downtown Northampton. It was known as The Beeches, and it was situated on a large lot, at the end of a long driveway. From the street, the house was almost entirely hidden by trees, offering a much greater degree of privacy than they had been able to enjoy here on Massasoit Street. Calvin Coolidge lived there for the rest of his life, and he died there in 1933 at the age of 60. Grace remained at The Beeches for several more years, but by the late 1930s she had moved to a house at 11 Ward Avenue, which stands less than a half mile away from their former home here on Massasoit Street.

The first photo shows the Massasoit Street house at some point during the late 1910s, probably when Coolidge was either lieutenant governor or governor. A century later, there have been a few changes, including the removal of the shutters and the balustrade over the porch on the right side, and the addition of a downspout on the front of the house. Overall, though, the exterior remains essentially the same as it did when Calvin Coolidge moved in here as a small-town attorney in 1906, and today it remains in use as a private residence. In 1976, the house was added to the National Register of Historic Places, but the only visible sign of its historical significance is a small plaque on the front porch, which identifies it as having been the home of Calvin Coolidge.