The Lenox Library, seen from the corner of Fifth Avenue and 70th Street in New York City, around 1900-1906. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene on December 20, 1913. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection.

The scene in 2019:

The modern concept of a public library in the United States began in the second half of the 19th century, and many such libraries had their origins in private libraries that were run by organizations or by wealthy benefactors. Here in New York City, these included the Astor Library and Lenox Library. Both were open to the public—with restrictions, particularly here at the Lenox Library—but they were intended primarily for researchers, and the books did not circulate. However, these two libraries formed the basis for the New York Public Library, which was established upon their merger in 1895.

The Lenox Library was the younger of the two institutions, having been established in 1870, although its founder, James Lenox, had begun collecting rare books several decades earlier. The son of wealthy merchant Robert Lenox, James inherited over a million dollars after his father’s death in 1839, along with a significant amount of undeveloped farmland in what is now the Upper East Side. He had studied law at Columbia, although he never actually practiced, instead spending much of his time collecting books and art.

For many years Lenox kept his collection in his house, which became increasingly overcrowded and disorganized. As a result, he created the Lenox Library in 1870, and that year he hired architect Richard Morris Hunt to design a suitable building, which would be located on Lenox-owned land here on Fifth Avenue, opposite Central Park between 70th and 71st Streets. It was one of the first major commissions for Hunt, who would go on to become one of the leading American architects of the late 19th century.

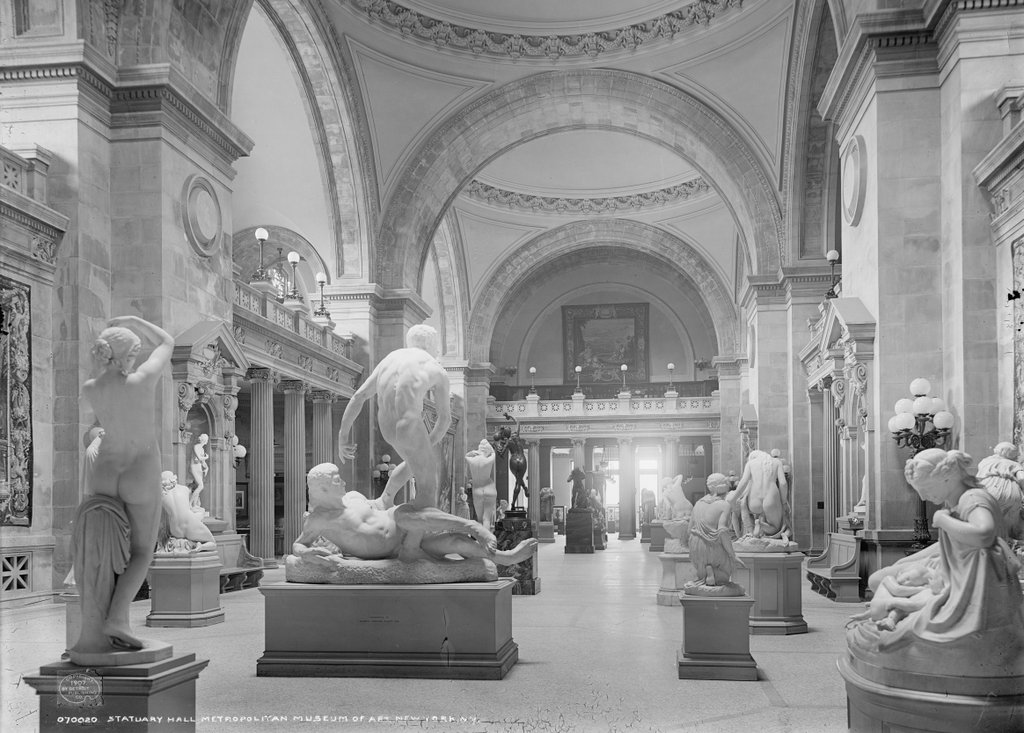

The building, shown here in the first photo, was completed in 1877. It was a combination library and art museum, featuring four reading rooms plus a painting gallery and a sculpture gallery. Admission was free of charge, but for the first ten years patrons were required to obtain tickets in advance by writing to the library, which would then send the tickets by mail. In any case, the collections here at the library would not have been of much interest to the casual reader. Because of Lenox’s focus on rare books, the library was, in many ways, more of a museum of old books than a conventional library. In addition, its holdings were far less comprehensive than most libraries, with a narrow focus on the subjects that Lenox was personally interested in.

Despite these limitations, though, the library was valuable for researchers searching for hard-to-find volumes. Perhaps the single most important book in its collection was a Gutenberg Bible, which Lenox had acquired in 1847. It was the first Gutenberg Bible to come to the United States, and it is now owned by the New York Public Library, where it is on display in the McGraw Rotunda. Other rare works included Shakespeare’s First Folio and the Bay Psalm Book, which was the first book published in the American colonies. Aside from books, the library also had important documents, including the original manuscript of George Washington’s farewell address, and its art collection featured famous paintings such as Expulsion from the Garden of Eden by Thomas Cole, and a George Washington portrait by Gilbert Stuart.

Overall, James Lenox contributed about 30,000 books to the library, which continued to grow after his death in 1880. By the 1890s, it had over 80,000 books, thanks to a number of significant donations and purchases. These additions helped to broaden the scope of the collection, making it more useful to the general public. However, the library struggled financially during the late 19th century, as did the Astor Library, and in 1895 they merged with the newly-created Tilden Trust to form the New York Public Library.

The new library subsequently moved into its present-day location at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street in 1911, and the former Lenox Library was sold to industrialist Henry Clay Frick, who demolished it to build his mansion on the site. A longtime business associate of Andrew Carnegie, Frick was the chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company, and by the 1910s he was among the richest men in the country. In 1918, for example, the first Forbes Rich List ranked him second only to John D. Rockefeller, with a net worth of around $225 million.

Frick had purchased the library property in 1906 for $2.47 million, but he had to wait until the library had moved its collections to the new building before he could take possession of the land. He ultimately acquired it in 1912, and demolished the old library that same year. His new home was then built here over the next two years, with a Beaux-Arts exterior that was designed by Thomas Hastings, a noted architect whose firm, Carrère and Hastings, had also designed the New York Public Library. The second photo shows the house in December 1913, in the midst of the construction. The exterior was largely finished by this point, but it would take nearly a year before Frick moved into the house with his wife Adelaide and their daughter Helen.

Like James Lenox, Frick was a collector, using his vast fortune to amass a variety of artwork and furniture. Upon his death in 1919, he stipulated that his house and its contents would become a museum, although Adelaide would be allowed to live here for the rest of her life. She died in 1931, and over the next four years the house was converted into a museum, opening to the public in 1935 as the Frick Collection.

Today, despite its changes in use, the exterior of the building from this view is not significantly different than it was when the first photo was taken more than a century ago. It still houses the Frick Collection, with the museum receiving around 300,000 visitors per year. Although not as large as many of the other major art museums in New York, it features a high-quality collection of paintings and furniture, including a good variety of works by the European Old Masters. The building itself is also an important work of art in its own right, and in 2008 it was designated as a National Historic Landmark in recognition of its architectural significance.