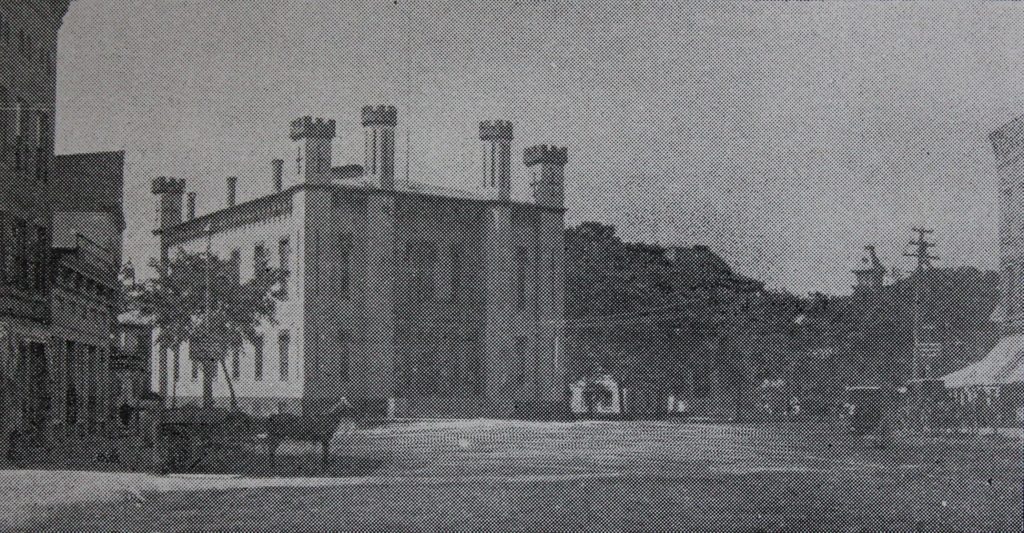

City Hall on Main Street in Northampton, around 1890. Image from Picturesque Hampshire (1890).

The scene in 2017:

Northampton’s city hall is perhaps one of the most unusual-looking municipal buildings in the state, with a distinctive Gothic-inspired exterior that stands about amid the more conventional brick commercial buildings that line Main Street. It was the work of William Fenno Pratt, a prominent local architect who designed a number of buildings in the area, and it was completed in 1850 as the town hall, since Northampton would not become a city for another 33 years. The building’s original layout included an auditorium on the second floor, which could accommodate over a thousand people. This space was often used for lectures, dances, and other civic events, and over the years a number of prominent people gave speeches here, including Henry Ward Beecher, Frederick Douglass, Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Lloyd Garrison, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Sojourner Truth.

Not long after Northampton became a city, this building played a role in the early political career of future president Calvin Coolidge. An 1895 graduate of Amherst College, he subsequently moved to Northampton and began practicing law, only a few years after the first photo was taken. In 1898, he was elected to his first political office as a city councilor, serving one term before being appointed as city solicitor. In 1904 he ran unsuccessfully for a seat on the school committee – the only election that he ever lost – but two years later he was elected as a state legislator. Then, in 1910 and 1911, he served two terms as mayor of Northampton, with his office here in city hall, before being elected to the state senate. From there, he held a succession of state offices, including senate president, lieutenant governor, and governor, and then in 1920 he was elected as vice president of the United States, before becoming president in 1923 upon the death of Warren Harding.

Around the same time that Coolidge became president in 1923, Northampton’s city hall was the center of controversy here in his hometown. The eclectic design of the building had long been unpopular with many people, including then-mayor Harry E. Bicknell, who derided its “flip-flops and flop-doodles,” as he put it. However, despite calls to replace it with a modern, more conventionally-designed building, frugality ultimately carried the day, since it was far cheaper to renovate the old building than to demolish it and build a replacement. The renovations did include some significant changes to the interior, including converting the auditorium into offices, but overall the exterior remained largely the same aside from the wooden crenellations atop the towers, which had rotted away by this point. Since they were entirely decorative and sat atop towers that, likewise, served no practical purpose, these crenellations would not replaced until the late 20th century.

Today, the building remains in use as Northampton’s city hall, still standing as an iconic feature on Main Street, with an appearance that is the same as it was over 125 years ago when the first photo was taken. The surrounding buildings have also changed very little over the years, including the 19th century commercial buildings on either side of the photo, as well as the 1872 Memorial Hall, located just to the right of City Hall. All of these buildings, along with the rest of the surrounding area, are now part of the Northampton Downtown Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.