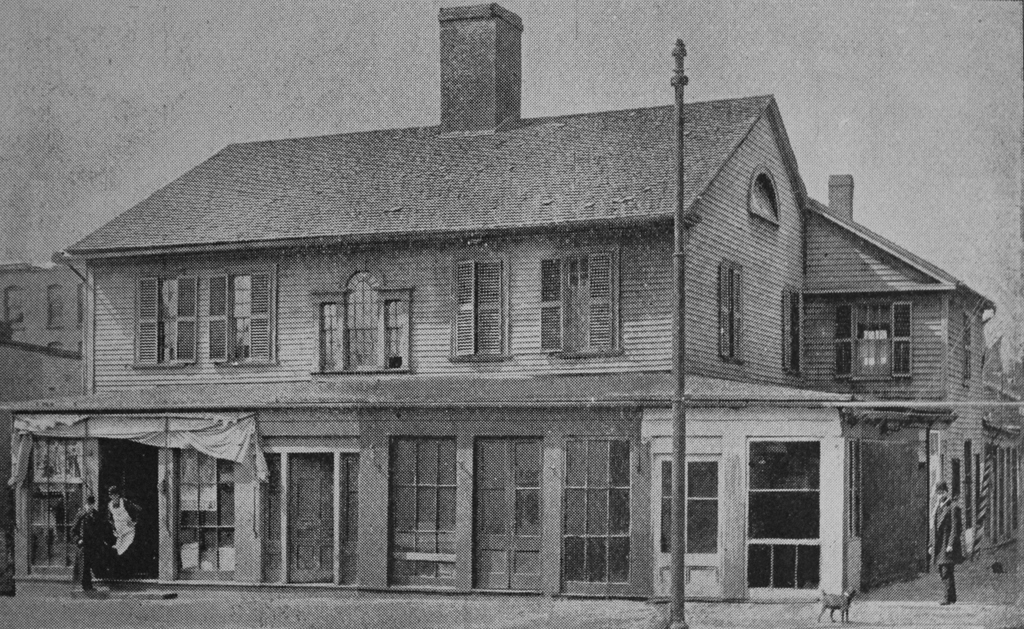

The gardens on the south side of The Elms in Newport, in 1914. Image taken by Frances Benjamin Johnston, courtesy of the Library of Congress, Johnston Collection.

The scene in 2018:

The first photo is from a lantern slide that was taken by Frances Benjamin Johnston, who was among the first prominent American women photographers. One of her specialties was garden photography, and in 1914 she took some photos of the gardens at The Elms, the summer estate of the Berwind family in Newport. These photos were taken in black and white, as color photography was still in its infancy at the time, but the resulting glass lantern slides were then hand colored, and Johnston used them in various lectures that she gave to garden clubs, museums, and other organizations.

This scene shows the gardens at the southwest corner of The Elms. The house had been constructed between 1899 and 1901, and it was used as the summer residence for Edward Julius Berwind, a Philadelphia native who had founded the Berwind-White Coal Mining Company. After making his fortune in the coal industry, Berwind joined the many other Gilded Age aristocrats who were building palatial homes here in Newport. He hired noted architect Horace Trumbauer to design the house, which was modeled after the Château d’Asnières, and the grounds were laid out by Ernest W. Bowditch, a landscape architect whose other Newport commissions included the grounds of The Breakers. Overall, the house cost about $1.4 million to build, equivalent to over $40 million today.

The house remained in the Berwind family for over 60 years. Edward and his wife Sarah had no children, but after her death in 1922 and his death in 1936, the property was inherited by his sister Julia. By this point, in the midst of the Great Depression, the heyday of the grand Newport mansions had passed. Such homes were increasingly seen as white elephants from a previous era, and many were either demolished or converted into different uses. However, life here at The Elms remained largely unchanged through all of this, with Julia continuing to spend her summers here, accompanied by 40 servants who ran the house.

The Elms was ultimately one of the last of the large Newport mansions to be staffed by such a retinue servants, and it was also one of the last that was still owned by its original family. This continued until 1961, when Julia Berwind died at the age of 96. Her nephew, Charles E. Dunlap, who was himself in his 70s at the time, then inherited the house. He had no interest in taking on the expense of maintaining the house, though, so he subsequently sold the property to a developer who intended to demolish the house and replace it with a shopping center.

This demolition nearly occurred in 1962, but at the last minute the property was sold to the Preservation Society of Newport County, becoming one of the organization’s many historic house museums here in Newport. Today, The Elms remains open to the public as one of the largest of the Gilded Age Newport mansions. Along with the house itself, the grounds have also been well-preserved during this time, including the sculptures visible here. Overall, very little has changed in this scene, with the gardens still looking much the same as they did when Frances Benjamin Johnston photographed them more than a century ago.