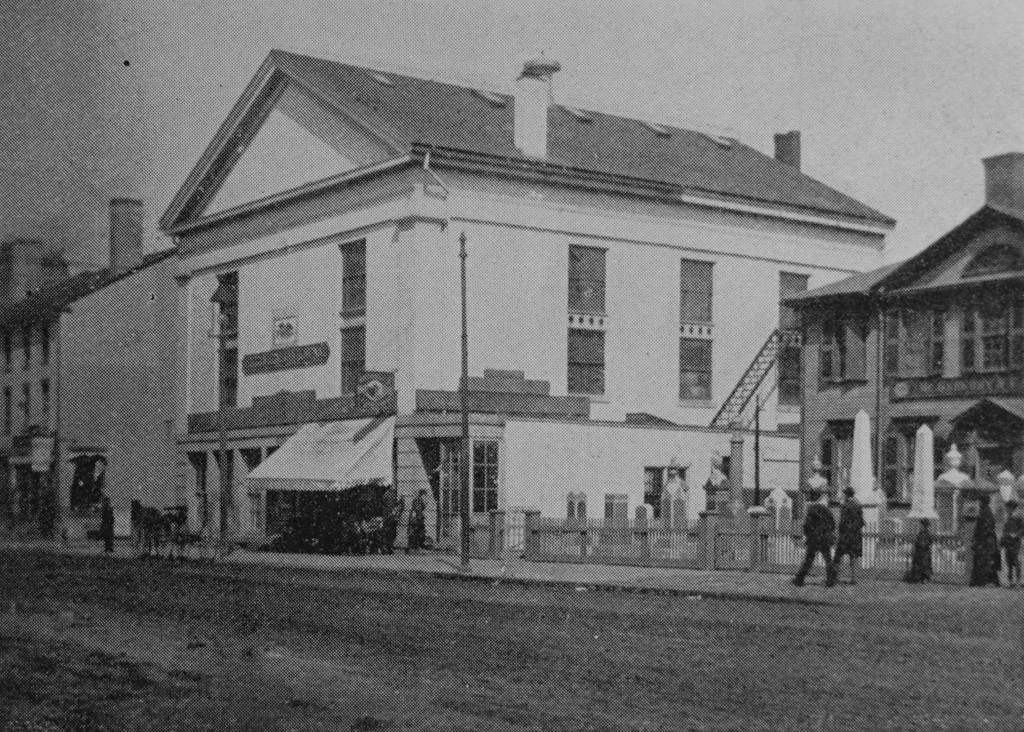

Looking up Cornhill from Washington Street, on April 14, 1897. Image courtesy of the City of Boston Archives.

The scene in 2016:

This narrow cobblestone street in downtown Boston connected Adams Square with nearby Scollay Square, and it was once a major literary center of the city, with many bookstores and publishers. When the first photo was taken, the early 19th century buildings here had a variety of businesses, with signs advertising for carpets, furniture, wallpaper, signs, trunks, and rubber goods. The first photo also shows a trolley coming down the street from Scollay Square, but this would soon change with the opening of the Tremont Street Subway in less than five months. Part of it was built under Cornhill, and it was the nation’s first subway, allowing trolleys to avoid the congested streets between Boston Common and North Station.

Nearly all of the buildings in the first photo were demolished in the early 1960s to build the Government Center complex. City Hall is just out of view on the right side of the 2016 photo, and the only building left standing in this scene is the Sears’ Crescent, partially visible in the distance on the left side of the street in both photos. Built in 1816 and renovated around 1860, this building still follows the original curve of Cornhill, serving as a reminder of what the neighborhood looked like before one of Boston’s most controversial urban renewal projects.