The painting A View of the Two Lakes and Mountain House, Catskill Mountains, Morning by Thomas Cole, 1844. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

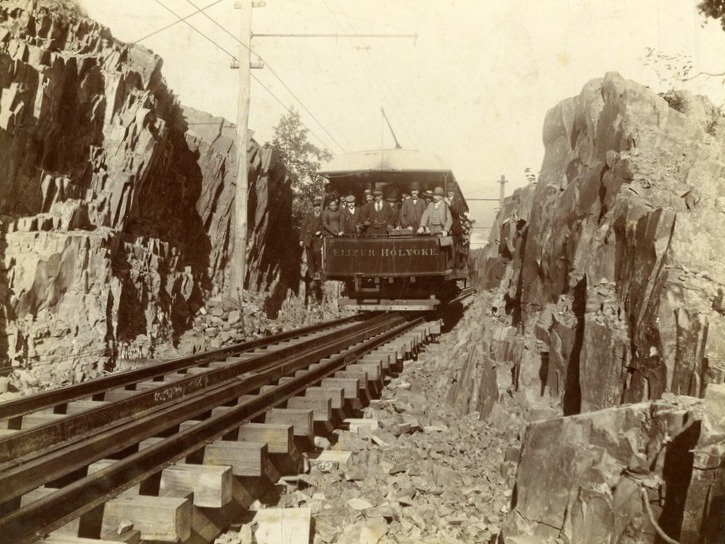

The scene around 1902. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2021:

These three views show the scene looking south from Sunset Rock, an outcropping along the Catskill Escarpment just to the north of North-South Lake. The lake, which was originally two separate lakes, is visible in the center of the scene, and beyond it is Kaaterskill High Peak, which rises 3,652 feet above sea level. For many years, this was believed to be the tallest mountain in the Catskills, hence its name, but surveys later in the 19th century proved that it was significantly shorter than Slide Mountain, and today it is ranked as only the 22nd highest in the range. On the far left side is the edge of the escarpment, which drops dramatically in elevation and forms the dividing line between the Catskill Mountains and the Hudson River Valley.

The early 19th century marked the beginning of mountain tourism in the United States, and the Catskills region was one of the first areas to experience this boom. Located along the west side of the Hudson River partway between New York City and Albany, the Catskills were within easy reach, and they offered dramatic scenic views, such as this one here on Sunset Rock. In 1824, the Catskill Mountain House opened near here, on a ledge overlooking the Hudson River Valley at a site known as the Pine Orchard. This was one of the first of many mountain resorts that would be built in the northeast over the course of the 19th century, and it drew many visitors here to enjoy the scenery of the Catskills.

Among the early visitors to the Mountain House was Thomas Cole, a young English-born painter who had immigrated to the United States as a teenager in 1818. He came here for the first time during the summer of 1825, and this visit would prove to have a transformative effect not only on Cole himself, but on the history of American art. He subsequently returned to his studio, where he painted five landscapes of the Catskills and Hudson River Valley, including his first major work, Lake with Dead Trees. These works helped to establish Cole as a prominent landscape painter, and they also marked the beginning of what would come to be known as the Hudson River School, a 19th century American art movement that emphasized dramatic landscapes of the country’s natural beauty.

Thomas Cole eventually relocated to the town of Catskill, where he lived and had his studio. He returned to the Mountain House area many times, but over the years he also expanded his works beyond the Hudson River area, with scenery of Europe, New England, and allegorical landscapes that did not depict a specific location. However, later in his career he painted one last grand landscape from up in the Catskills, shown here in this post. Titled A View of the Two Lakes and Mountain House, Catskill Mountains, Morning, it shows the scene from Sunset Rock, with the Mountain House in the distance on the left side of the painting. As was typical for Cole’s works, it highlights the grandeur of the natural environment. In contrast to the expansive scenery, the only signs of human presence are the small figure in the foreground and the distant hotel, both of which are surrounded by the wilderness.

Nearly 60 years after Thomas Cole painted this view, a photographer captured the same scene with a camera, as shown in the second image. As shown in the photo, remarkably little had changed here since Cole’s visit, and the Catskills remained a popular tourist destination. The Catskill Mountain House was still standing on the left side, although by this point it had been joined by a rival, the Hotel Kaaterskill, which is visible directly below the summit of Kaaterskill High Peak in the 1902 photo. It had been built in 1881, and it stood atop South Mountain, which was about a mile to the southwest of the Mountain House and several hundred feet higher in elevation.

The Hotel Kaaterskill was built by Philadelphia lawyer George Harding, whose motivations evidently had more to do with spite than any other considerations. As the story goes, Harding had visited the Mountain House during the summer of 1880, and during one meal he requested fried chicken for his daughter. However, the kitchen refused to prepare fried chicken since it was not on the menu, and Harding ended up in an argument with owner Charles Beach, who told him he could build his own hotel if he wanted fried chicken. Harding did exactly that, and his Hotel Kaaterskill opened less than a year later. After several expansions over the next few years, it grew to 1,200 guest rooms, and it was said to have been the largest mountain hotel in the world, along with the largest wood-frame hotel in the world.

Mountaintop resorts such as the Mountain House and the Hotel Kaaterskill had enjoyed a heyday during the 19th century, but by the early 20th century the preferences of travelers had begun to change. Part of this was because of the automobile, which opened up new travel opportunities beyond what was accessible by rail. The buildings themselves were also aging, and they were particularly susceptible to fire, given their elevated locations and wood-frame construction. Such was the case with the Hotel Kaaterskill, which was completely destroyed by a massive fire in 1924. As for the Mountain House, it had been one of the first mountaintop resorts, and it managed to outlive most of its contemporaries, but it closed in 1942 and steadily deteriorated over the next few decades. The property was eventually acquired by the state of New York in 1962, and the historic building was deliberately burned the following year.

Today, nearly two centuries after Thomas Cole first visited this area and launched an artistic movement, this scene from Sunset Rock has remained essentially unchanged. In fact, there are actually fewer signs of human activity now than in either the painting or the 1902 photograph, since both hotels are now long gone. The two lakes are now united as one, but otherwise the only hint of modernity in the 2021 photo is a power line that runs along the shoreline of the lake in the center of the photo. This area remains a popular among summer visitors, although they spend their time here in very different types of accommodations. Rather than large, opulent 19th century resort hotels, visitors instead camp at the North-South Lake Campground, which has over 200 campsites, mostly on the north side of the lake.