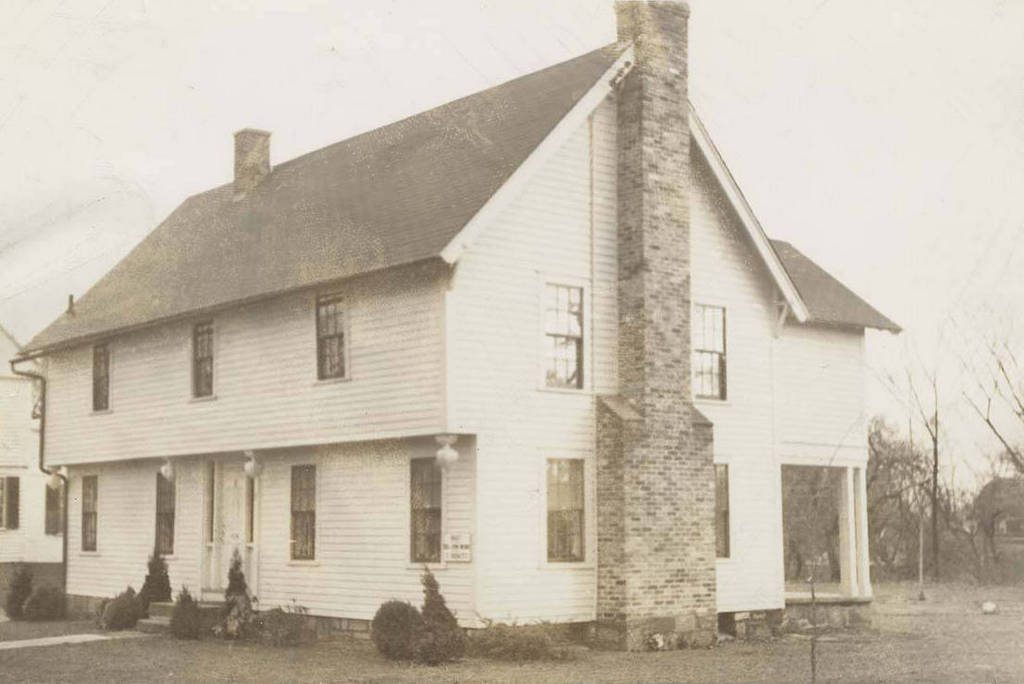

The house at 37 Elm Street in Windsor, around 1938-1942. Image courtesy of the Connecticut State Library.

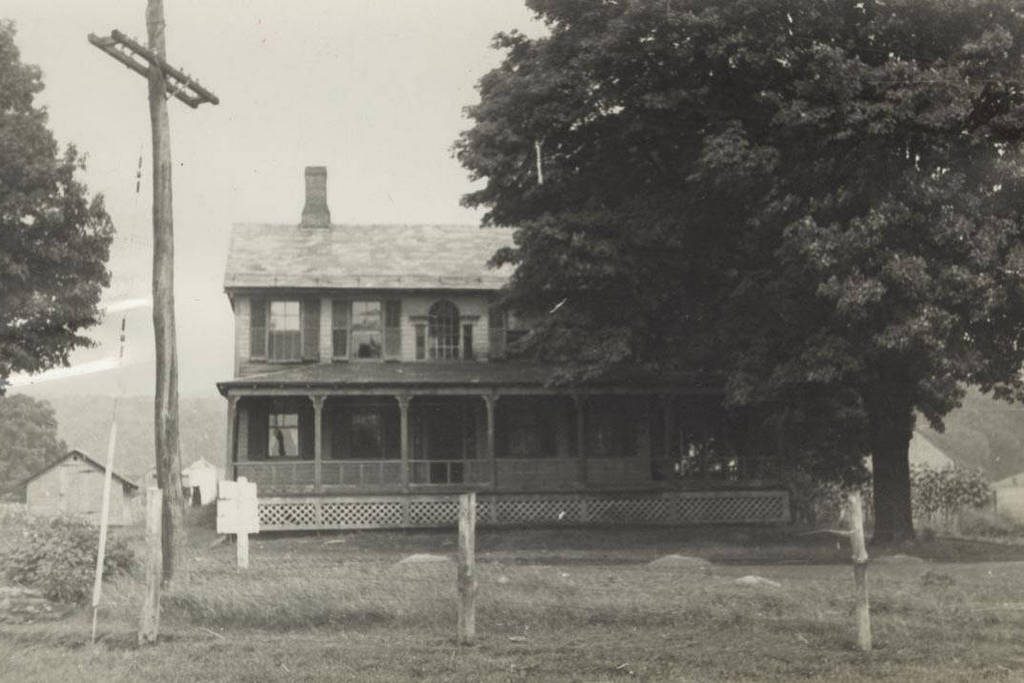

The house in 2017:

The town of Windsor is, arguably, the oldest in Connecticut, and it has no shortage of historic houses. Some of the oldest houses in the state are located here in Windsor, and this house is among the oldest, dating back to around 1664. It has been moved several times and considerably altered over the years, with very little of the original material surviving except for the frame itself, but it still stands as a rare example of post-Medieval architecture in the Connecticut River Valley.

This house was built for John Moore, one of the early settlers of Windsor and a leading citizen here. He and his father, Thomas Moore, had immigrated to America in 1630 and settled in Dorchester, where they lived until 1639, when they moved to the newly-established town of Windsor, located along the banks of the Connecticut River. Here, they joined a number of other Massachusetts expatriates in the new colony, and John soon rose to prominence. He was elected to represent the town in the General Court in 1643, and in 1651 he was ordained as a deacon in the town’s church.

When John Moore built this house around 1664, it was located near here at the corner of Broad and Elm, facing east at the town green. He lived there for the rest of his life, until his death in 1677, and the house remained in his family for several more generations. His only son, John Moore Jr., inherited the house, and subsequently gave it to his son Thomas, who was living here by the 1690s.

The house stood at its original location on Broad Street until around 1805, when it was purchased by William Loomis. He moved it a short distance and attached it to a new house that he had built, with the old Moore house becoming a wing for the kitchen. The conjoined homes were later used as an inn, and they stood attached for nearly a century. At this point, though, the historical significance of the Moore house was already recognized, and it was mentioned in Henry Reed Stiles’s 1859 book The History of Ancient Windsor, Connecticut. In the book, he writes that the house “was in its day, and even within the recollection of some now living, a fine house, but is now degraded to the humble office of a kitchen to a more modern house which occupies its original site.”

This arrangement continued until 1897, when Horace Clark purchased the property. He separated the two houses and moved them around the corner onto Elm Street, where they were situated on adjacent lots on the south side of the street. The Moore house was heavily modified during this time, including the removal of the original central chimney and the addition of a large front porch, along with significant interior alterations.

After the 1897 move, the house was still facing east, with the front facade perpendicular to Elm Street. However, in 1938 the house underwent another renovation, which included the removal of the front porch and the 1890s chimneys. As part of this renovation, the house was also rotated on the lot, so that the front faced north toward Elm Street. The first photo was taken shortly after this work was done, and at this point almost nothing was left of the original house besides the frame. Remarkably, though, three of the seemingly-delicate pendants beneath the front overhang are original to the house. Only the one on the far right is a modern replica, with the original having been removed when that side of the house was joined with the Loomis House. Additionally, two ornamental brackets under the left gable are also original, although they are not visible from this angle.

Nearly 80 years after the first photo was taken, very little has changed in this scene. The Loomis house still stands on the adjacent lot, where it is partially visible on the left side of both photos, and the Moore house, now over 350 years old, stands as one of the oldest surviving houses in New England. Because of this, and despite the significant changes over the years, the house was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.