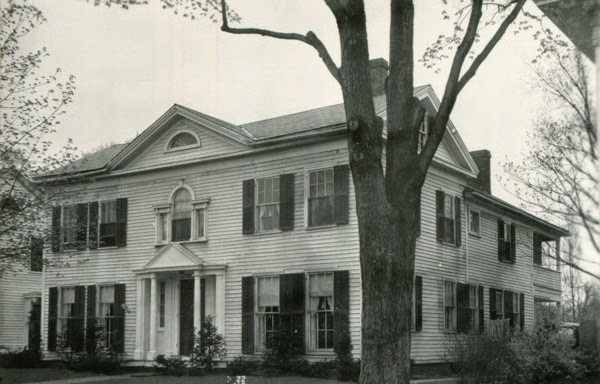

The house at 5 Ridgewood Terrace, at the corner of Union Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The house in 2017:

Albert W. Fulton was born in Iowa in 1859, but later moved to Chicago, where he worked as a reporter and commercial editor for the Chicago Tribune. However, he came to Springfield in 1893, and that same year he married his wife, Rena E. Day. Early in their marriage, they lived in a new house on Spruceland Avenue in the Forest Park neighborhood, but around 1909 they moved into this newly-completed, much larger house on Ridgewood Terrace. At the time, Fulton was the treasurer of the Phelps Publishing Company, a Springfield-based firm that published a variety of agricultural-related periodicals, including the New England Homestead, Farm and Home, American Agriculturalist, Orange Judd Farmer, and, perhaps most notably, Good Housekeeping.

Albert and Rena had two daughters, Dorothy and Anna, and they lived here until about 1924, when they moved to a nearby house at 372 Union Street. Albert would eventually go on to become president of Phelps Publishing, and he lived in Springfield until his death in 1938. In the meantime, this house was sold to William S. Warriner, who was living here during the 1930 census, along with his wife Jennie. He was an insurance agent, but he was also involved in politics, having previously served as a city alderman and as a state legislator. Along with this, he was a veteran of the Spanish-American War, where he was badly wounded in Cuba, and he went on to serve for many years in the state militia, eventually attaining the rank of colonel.

The Warriners were still living here when the first photo was taken in the late 1930s, but they moved out soon afterward, because by 1940 they were living nearby on Mulberry Street. The house was then sold to Raymond H. Kendrick, an Episcopal priest who was serving as canon of Christ Church Cathedral. He was native of Springfield, and the son of former mayor Edmund P. Kendrick, but after completing his education he served in a number of different churches, including in Albany, New Bedford, Boston, and North Andover, before finally returning to Springfield. After purchasing this house on Ridgewood Terrace, he and his wife Sarah went on to live here for the rest of their lives, until her death in 1956 and his death in 1968.

Nearly 80 years after the first photo was taken, very little has changed with the Ridgewood area. Developed at the turn of the 20th century with a number of upscale homes, this area between Union and Mulberry Streets has retained its original appearance, including here at the corner of Ridgewood Terrace and Union Street. Both this house and the neighboring house to the left at 351 Union are well-preserved, and they are now part of the city’s Ridgewood Local Historic District.