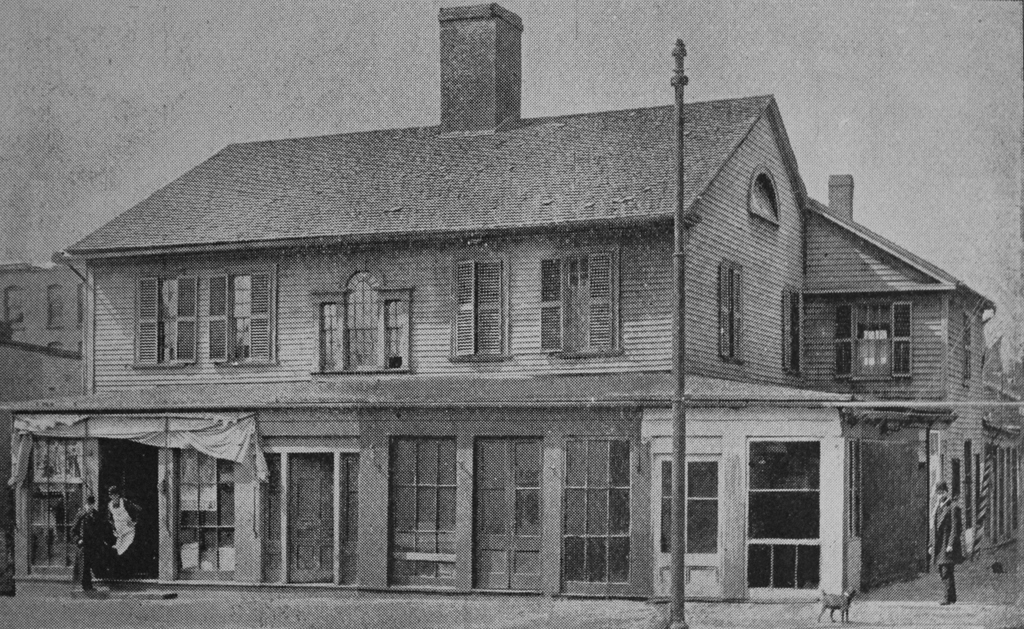

The Hetty Green House at the corner of Church and Westminster Streets in Bellows Falls, around 1900-1910. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2018:

It is hard to tell from its appearance, but this house was the home of the wealthiest woman in America when the first photo was taken at the turn of the 20th century. Throughout her life, even after she had amassed a fortune worth many millions of dollars, Wall Street financier Hetty Green lived a very frugal—and some would say miserly—lifestyle. She wore plain, old clothing, ate inexpensive meals, and shunned most luxuries, supposedly even heat and hot water.

Her house here in Bellows Falls was another example of her modest living. Although certainly a fine house in its own right, it was hardly befitting of a Gilded Age tycoon, especially considering the lavish mansions that many of her contemporaries, most notably the Vanderbilts, were constructing in New York, Newport, and other fashionable places.

The house itself was situated at the corner of Church and Westminster Streets, just to the south of the center of Bellows Falls. It was built in 1806 by William Hall, a wealthy local merchant in the firm of Hall & Green. Hall was also involved in politics, serving on the governor’s council, in the state legislature, and as Vermont’s sole delegate to the 1814-1815 Hartford Convention. He lived here in this house until his death in 1831, at the age of 57, and the house was subsequently purchased by Nathaniel Tucker, the owner of the nearby Tucker Toll Bridge over the Connecticut River.

Nathaniel Tucker had connections to William Hall, as his daughter Anna was married to Hall’s former business partner, Henry Atkinson Green. Their son, Edward Henry Green, would eventually become a successful Boston merchant, and in 1867 he married Henrietta “Hetty” Robinson, the wealthy heiress of a New Bedford whaling family. Then, in 1879 he purchased his grandfather’s old house here in Bellows Falls, and moved his family into it.

Hetty Green was 33 years old when she married Edward, and she was already extremely wealthy, having inherited about $6 million after her father’s death two years earlier. However, her fortune would continue to grow thanks to her shrewd investment strategies, and she came to be known as the “Witch of Wall Street”at a time when high finance was almost exclusively a male profession. By the time she died in 1916 at the age of 81, her estate was valued at over $100 million, equivalent to over $2 billion today, making her the richest woman in America at the time.

Hetty and Edward had two children, Ned and Sylvia, who were about 11 and 8 years old, respectively, when their father purchased this house. During his childhood, Ned became the subject of one of the most famous examples of his mother’s frugality after he injured his knee. Wanting to avoid paying for a doctor, Hetty instead tried to treat him herself. However, infection set in and the leg became gangrenous, and it ultimately had to be amputated.

In adulthood, Ned spent his money much more freely than his mother had. He owned a 225-foot steam yacht, and he built a mansion on Buzzards Bay in Massachusetts, which featured his own private airfield and radio station. In addition, he was an avid collector of coins and stamps, and at one point his collection included all five examples of the extremely rare 1913 Liberty Head nickel, along with the only known sheet of the famous Inverted Jenny postage stamp. Ned also played an important role in historic preservation when, in the 1920s, he purchased the former whaling ship Charles W. Morgan, which had once been a part of his maternal grandfather’s whaling fleet. He put it on display at Round Hill, and after his death it was acquired by Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, where it remains as the last surviving 19th century whaling ship.

Ned’s sister Sylvia, however, was much more like their mother when it came to saving money. In 1909 she married Matthew Wilks, a member of the Astor family who was 25 years her senior, although her mother insisted that they sign a prenuptial agreement to prevent Wilks from inheriting Sylvia’s money. Neither Sylvia nor her brother had any children, and after Ned’s death in 1936 Sylvia inherited his portion of the estate, as a result of a similar prenuptial agreement that he had signed with his wife, Mabel Harlow. Later in life, though, Sylvia became both miserly and reclusive, and her last public appearance was in 1937, when she testified in court to prevent Mabel from receiving a greater share of Ned’s fortune.

Upon her death in 1951 at the age of 80, Sylvia was described by Life magazine as “a friendless, childless, cheerless old woman, abjectly poor in everything but money and devoted only to the preservation of the great Green fortune.” Her net worth at the time was around $95 million, nearly $1 billion today, but with no children or other close relatives she left nearly all of her money to 63 different charities, including a variety of churches, libraries, and hospitals. Among these were the Rockingham Memorial Hospital and the Immanuel Episcopal Church, both of which are located here in Bellows Falls.

In the meantime, the old house here on Church Street in Bellows Falls remained in the Green family until 1940, although Sylvia does not appear to have spent much time here in her later years. By this point the house was in need of repairs, so rather than restoring it, Sylvia had the house demolished, and then gave the property to the town. The property subsequently became a parking lot and a park, which was named Hetty Green Park.

Today, park is still here, on the far right side of the scene, but the actual site of the house is now a bank, which was constructed in 1960. It was originally the Vermont Bank & Trust Company, but after a series of mergers in the late 20th century it is now owned by TD Bank, which continues to operate it as a branch. The bank building certainly does not have the same architectural or historic significance that the old house had, although in retrospect it seems only appropriate that Hetty Green’s former property would be used as a place where large amounts of money are kept.