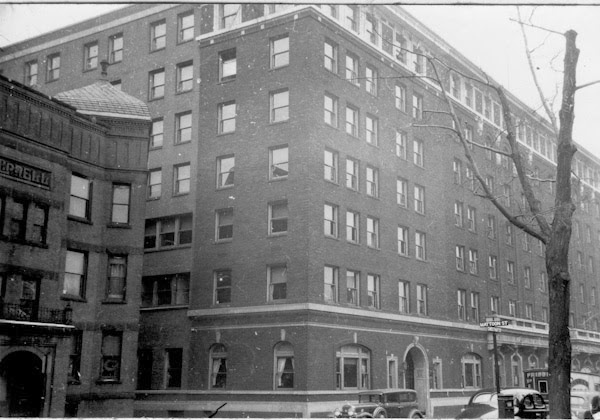

The houses at 94-98 Elliot Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The scene in 2018:

These three brick townhouses were constructed around 1870, at the corner of Elliot and Salem Streets. The lot had been purchased by Benjamin F. Farrar, a local mason who built the houses and then sold them to new owners. The one on the far left, at 94 Elliot Street, became the home of William Mattoon, who would soon develop Mattoon Street, located just around the corner from here. In the middle, 96 Elliot Street was sold to Harriet Wright, a widow who was in her mid-40s at the time. On the right side, at the corner of Salem Street, 98 Elliot Street was sold to William H. Wright, a wealthy tobacco dealer who had no apparent relation to Harriet Wright.

As it turned out, none of these three original residents would live here for very long, and by the 1880 census all three homes had new owners. On the left side was Hiram C. Moore, one of the city’s leading studio photographers. He previously had a partnership with his brother Chauncey, but by 1880 he was in business for himself, with a studio at the corner of Main and Bridge Streets. That year’s city directory included an advertisement for his business, which was proclaimed as “the place to get all the latest novelties in the Photographic Art, being the largest and best appointed gallery in the county. The only place where those beautiful crystal pictures are made, and also the only place where instantaneous pictures are made of the little ones.”

Moore’s neighbor to the right, in the middle house, was Zenas C. Rennie, who was living here in 1880 with his wife Margaret, their two children, a boarder, and a servant. He had been an officer during the Civil War, eventually earning the rank of major, and after the war he entered the insurance business. By 1880 he had moved to Springfield, where he worked as the city’s general agent for the Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York, with his office in the same building as Moore’s studio.

Also during the 1880 census, the house furthest to the right was the home of druggist William H. Gray. He was a partner in the H. & J. Brewer pharmacy, located at the corner of Main and Sanford Streets, and he would later become the vice president of the Springfield Five Cents Savings Bank. In 1880, he was living here with his wife Sarah and their three-year-old son Harry, in addition to two boarders and a servant. The family would live here for at least a few more years, but by 1883 they had moved into a newly-built house on Madison Avenue.

Twenty years later, the 1900 census shows that Hiram Moore was still living here in the house on the left, along with his wife Jennie, three children, and a servant. He was still working as a photographer, but the city directory also listed his occupation as “patent rights and novelties.” Next door, the middle house was owned by real estate agent Orson F. Swift, who lived here with his wife Cornelia and their daughter Kate. However, in a sign of things to come, the house on the right had become a rooming house, with the 1900 census showing five residents living here.

By the time the first photo was taken in the late 1930s, all three of these houses – along with many of the 19th century townhouses around the corner on Mattoon Street – had been converted into either apartments or rooming houses. The 1940 census shows that Hiram Moore’s former house on the left had been divided into four units, with a total of nine residents. The other two houses were used as rooming houses, with seven people living in the middle house and nine in the house on the right. Curiously, one of these tenants in the latter house was Herbert Wilson, who was listed as being employed by the WPA Building Survey. This almost certainly referred to the Depression-era project that documented and photographed every building in the city. The first photo was taken as part of this survey, and perhaps may have even been taken by Wilson himself.

Today, this scene is not significantly different from when the first photo was taken some 80 years earlier. After having gone from upper middle class single-family homes to Depression-era rooming houses, these three houses are still standing today, with exteriors that have been well-preserved. The nearby townhouses on Mattoon Street have similarly been restored, and collectively these houses – along with a number of other historic properties in the area – are now part of the Quadrangle-Mattoon Street Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.