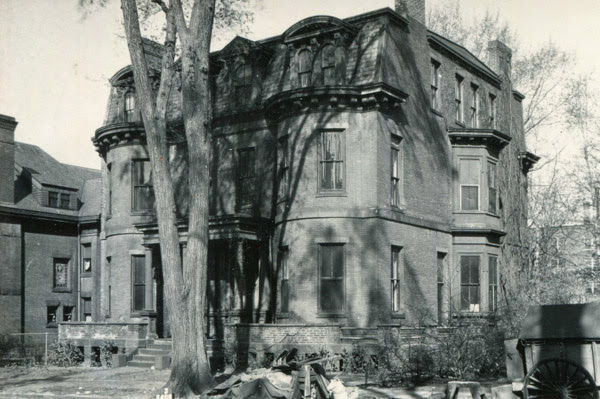

The house at 26 Ridgewood Terrace in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

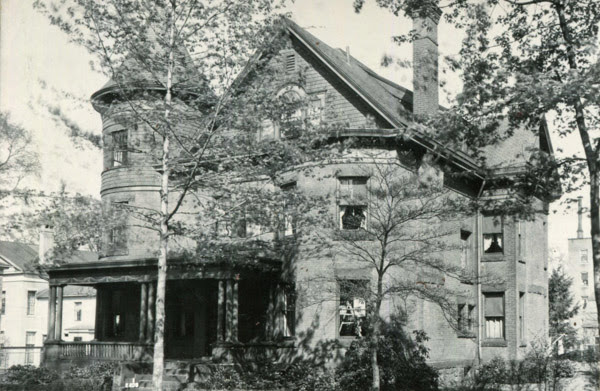

The house in 2017:

This area between Union and Mulberry Streets was once the home of Colonel James M. Thompson, who built a mansion here in 1853. It was situated on a large, beautifully landscaped lot that offered views of downtown Springfield, the Connecticut River, and beyond. Colonel Thompson died in 1884, and about a decade later his widow sold the property to William McKnight, the developer of the city’s McKnight neighborhood. He subdivided the lot, demolished the old mansion, and built a number of upscale houses along Union Street, Mulberry Street, Ridgewood Place, and Ridgewood Terrace.

The Tudor Revival-style house in these two photos was one of the finest in the development. Like almost all of the other Ridgewood homes, it was designed by G. Wood Taylor, an architect who was also McKnight’s son-in-law. It was completed in 1896, and its first owner was John A. Hall, the president of the Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company. Born in New York in 1840, Hall had come to Springfield during the Civil War to work in the Armory. After the war, he began working for MassMutual, and despite no prior experience in the insurance industry he soon advanced in the company, eventually becoming secretary in 1881 and then president in 1895.

John Hall married his wife Frances while he was still working at the Armory, and they had two children, Clara and John, Jr. All four of the family members were living in this house during the 1900 census, along with three servants. However, John died in 1908 while traveling overseas in London, and this house was subsequently sold. Two years later, his son committed suicide at the Maplewood Hotel in Pittsfield, at the age of 30. According to contemporary newspaper accounts, he had called a barber to his hotel room for a shave, asked the barber to see the razor, and then used it to cut his throat.

In the meantime, the new owner of this house was Albert Steiger, the founder of the Springfield-based Steiger’s department store. Steiger had immigrated from Germany to the United States as young boy in 1868, and when he was a teenager he began working for a dry goods merchant in Westfield. He eventually opened a store of his own in Port Chester, New York, and in 1896 he opened a second store in Holyoke, followed by a third in New Bedford in 1903. Then, in 1906, he opened what would become his flagship store in Springfield, at the corner of Main and Hillman Streets.

Despite competition from other, more established nearby department stores such as Forbes & Wallace, Steiger’s became successful, and just a few years after opening the store Albert Steiger moved into this mansion on Ridgewood Terrace. He and his wife Izetta had five sons, Ralph, Phillip, Chauncey, Robert, and Albert, Jr. All of them went on to work for their father’s company, and the two youngest also served in World War I. In the meantime, the company continued to expand, opening a store in Hartford in 1919, and by 1924 his stores were bringing in some $15 million in annual sales, equal to over $200 million in today’s dollars.

Albert Steiger lived here until his death in 1938, right around the time that the first photo was taken. In the 1940 census, his son Ralph was living here, along with Robert and Albert, Jr. However, by the early 1950s it was sold and converted into the Ring Nursing Home. It was in use as a nursing home until the 1990s, and has since been converted into a group home for children. Despite all of these changes, though, both the house and the surrounding area have remained well-preserved. Nearly all of the homes that McKnight built here are still standing, and now form the city’s Ridgewood Local Historic District.