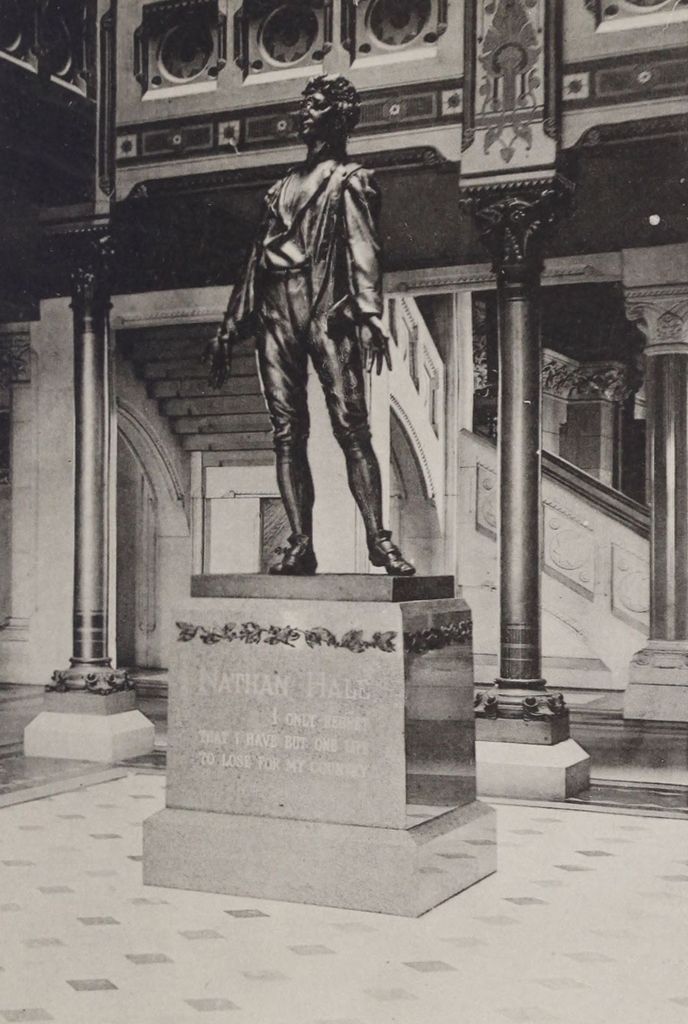

The main staircase in the Longfellow House on Brattle Street in Cambridge, around 1910-1920. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2019:

As discussed in more detail in an earlier post, this house was built in 1759 for John Vassall, a wealthy sugar plantation owner who fled Cambridge just prior to the start of the American Revolution because of his loyalist sympathies. The patriot government then confiscated his property, and from July 1775 to April 1776 it was the residence and headquarters of George Washington, who had been given command of the Continental Army just before coming to Cambridge. Much of his strategic planning during the Siege of Boston was done here in the house, including his move to fortify Dorchester Heights in March 1776, which ultimately led to the British evacuation of Boston.

Aside from Washington, the other famous resident of this house was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He moved in here in 1837 as a boarder, when he was a 30-year-old Harvard professor and still a relatively obscure writer. His future father-in-law, Nathan Appleton, later purchased it as a wedding gift for Longfellow and his wife Fanny in 1843, and he went on to live here for the rest of his life. In total, he spent 45 years in this house, and most of his major works were written here, including Evangeline, The Song of Hiawatha, “Paul Revere’s Ride,” and “The Village Blacksmith.”

This staircase is located just inside the front door, so it would have been the first thing that guests of both Washington and Longfellow would have seen upon arriving in the house. Both of these famous residents had a number of notable visitors here, and for Washington these included his subordinate generals such as Horatio Gates, Artemas Ward, Charles Lee, Israel Putnam, and Nathanael Greene. Many of Longfellow’s prominent visitors were fellow literary figures, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Charles Dickens, Oscar Wilde, and William Makepeace Thackeray.

Although not visible in this scene, the entry hall also features two doors at the base of the stairs, with one on the left and one on the right. The door to the left leads into the room at the southwest corner of the house, which was used by Washington as his reception room for his visitors, and by the Longfellows as their parlor. To the right, at the southeast corner, is where Washington had his dining room, and where he would have held his councils of war with his other generals. This room was later used by Longfellow as his study, and he wrote many of his famous works there.

Longfellow appreciated the history of his house and its association with Washington. When the general first arrived here in July 1775, the patriot leaders had great confidence in his abilities, but at that point his leadership had not yet been tested in battle. However, by the time Longfellow moved in more than 60 years later, Washington was revered as the father of his country, and he was the subject of countless works of art. In 1844, to recognize Washington’s time here in this house, Longfellow purchased a bust of Washington, which he placed here in the entry hall. It was a copy of one made by Jean-Antoine Houdon in 1785, and, as these two photos show, it is still here next to the stairs, nearly 180 years later.

Longfellow’s daughter Alice had a similar respect for history and historic preservation, so after his death in 1882 she was careful to maintain both the interior and exterior appearances of the house. As a result, the first photo, which was taken around the 1910s, when Alice was still living here, probably reflects how it would have looked during Longfellow’s lifetime. Aside from the bust of Washington, the photo also includes several other antiques and works of art. On the left side are three paintings, and above them is a print of Washington on horseback that Longfellow acquired in 1864. In the upper center of the scene, on the landing, is a grandfather clock that he added there in 1877, five years before his death. As shown in the 2019 photo, all of these objects are still in the same location today.

For much of the 20th century, this house was run by the Longfellow House Trust. However, in 1972 the organization gave the house and its contents to the National Park Service, and it became the Longfellow House National Historic Site. It has since been renamed the Longfellow House–Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site, but, as these photos show, not much else has changed here, and the house is open to the public for ranger-guided tours.