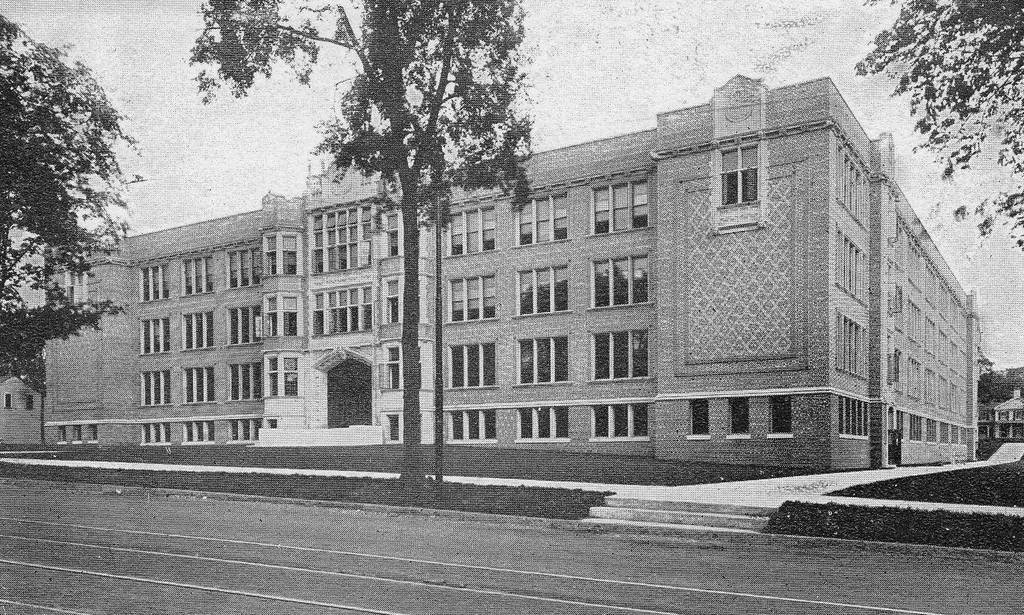

The High School of Commerce on State Street in Springfield, around 1915-1920. Image from the Russ Birchall Collection at ImageMuseum.

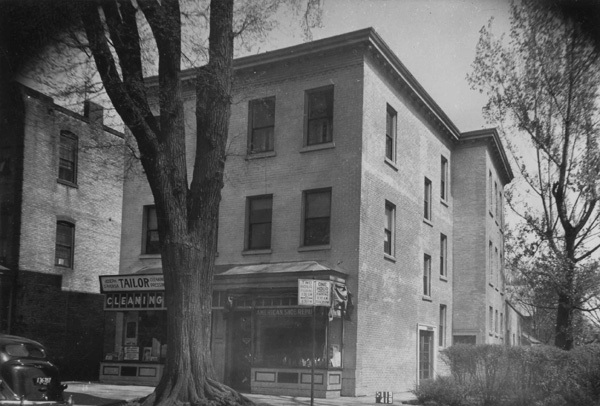

The school in 2019:

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Springfield saw dramatic growth as the city became an important regional center for business and industry. For example, in a 40 year span from 1880 to 1920, the city nearly quadrupled in size from 33,000 to nearly 130,000. However, during this same period the city’s public school system grew even more rapidly, particularly with high school students. During the 1878-1879 school year, the city had one high school with nine teachers and a total enrollment of 417. But, 40 years later the number of high school students had increased by more than eightfold to 3,437 in three different schools.

Much of this growth was because of the changing nature of high school. During the 19th century, a high school education was by no means universal, and these schools often focused primarily on preparing students for college. However, this began to change by the turn of the 20th century, particularly here in Springfield, where there was a high demand for well-educated workers. This led to the establishment of a technical high school, which focused on preparing students for careers in science, technology, and skilled trades, and a high school of commerce, which prepared students for business careers. Given that the city had a wide variety of manufacturers, insurance companies, banks, and other large corporations, graduates from these schools would not have to look far in order to find job opportunities.

The city’s first public technical high school was the Mechanical Arts High School, which opened at Winchester Square in 1898, but in 1906 it became the Technical High School and moved into a new building on Elliot Street. Four years later, the city established the High School of Commerce. It was originally located in Central High School, which was later renamed Classical High, but in 1915 Commerce moved into a building of its own, located here on State Street opposite the Springfield Armory, and within easy walking distance of the other two high schools.

The High School of Commerce building was designed by local architect Guy Kirkham, with a Tudor Revival-style exterior of red brick and limestone. Upon completion, it featured over 60,000 square feet of floor space, and it had a capacity of 1,500 students. It opened on September 7, 1915 with a dedication ceremony in the auditorium, which included speeches by principal Carlos B. Ellis, superintendent James H. Van Sickle, and mayor Frank E. Stacy. This was followed by a flag raising ceremony here in front of the building, accompanied by a 21-gun salute from the Armory.

When this building opened, it had 1,058 students and 44 teachers, but it steadily grew over the next few decades, requiring some reconfiguration of the interior in order to accommodate more students. By 1933 it had 2,292 students—including my grandmother, who graduated with the class of 1935—and 83 teachers. These numbers would drop during World War II, reaching as low as 1,250 students in 1943, although enrollment would rise again after the end of the war.

The first photo was taken shortly after the school opened, but very little has changed in this scene in more than a century since then. The building stands as the oldest of the city’s five high schools, and it currently has an enrollment of just over a thousand students. It is still called the High School of Commerce, although this name is largely vestigial, because its curriculum no longer specifically focuses on preparing students for business careers. Overall, though, its exterior appearance is essentially the same as it was when it opened in 1915. The only significant difference is a large addition, which was completed in the late 1990s. It is not visible from this angle, but it is located behind and to the left of the main school, and connected to it by a covered walkway.