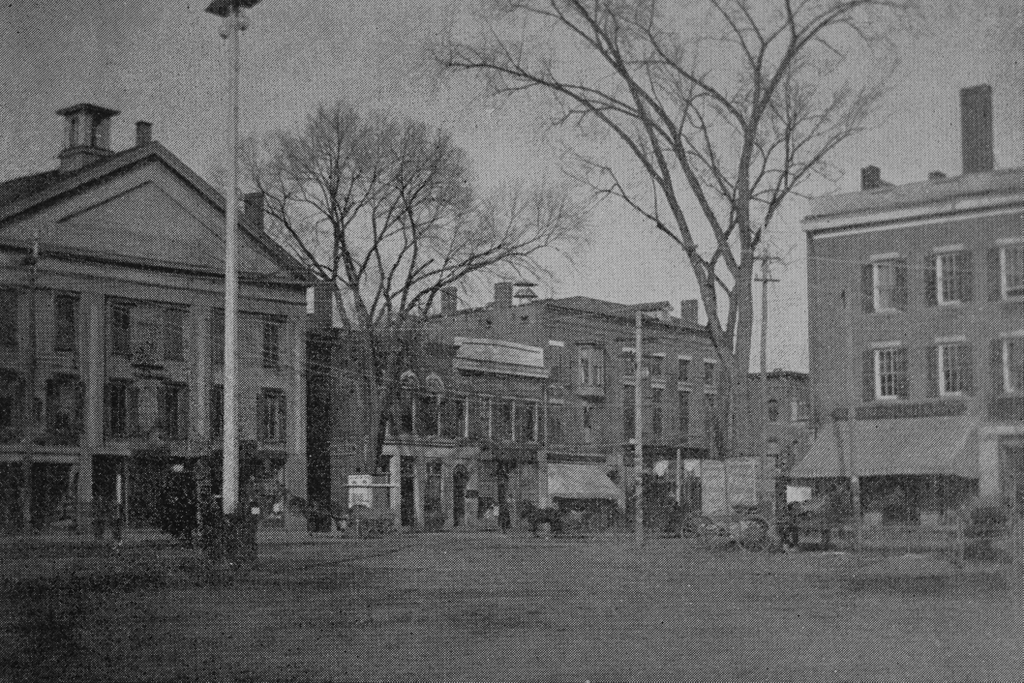

The buildings at the northeast corner of the Square in Bellows Falls, around 1890-1905. Image courtesy of the Rockingham Free Public Library.

The scene in 2018:

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, downtown Bellows Falls suffered a series of devastating fires, many of which were located here at the Square. Many large brick buildings here, including the nearby Hotel Windham and the town hall on the other side of the street, have burned over the years. Ironically, though, the three wood-frame buildings visible in this scene have survived these fires, and they are still standing at the northeast corner of the Square, well over a century after they were built.

On the far left is the corner of a three-story commercial block that was built around 1820 and extensively modified in 1890. By the turn of the 20th century, around the time that the first photo was taken, it was the home of Baldasaro’s Fruit Market. Just to the right of this building is the Exner Block, which is partially visible in this scene at 7-25 Canal Street. Built around the mid-19th century, it originally had two stories as shown in the first photo, but in 1905-1907 it altered and expanded to its current appearance.

The third wood-frame building here is the Brown Block, which occupies most of the left side of these photos. It was built in 1890 at 1-5 Canal Street, and it was originally owned by Amos Brown. It features distinctive Queen Anne-style architecture, which is uncommon for commercial buildings in Bellows Falls, including a turret on the right side of the building.

The Brown Block was heavily damaged by a fire that occurred here in the early morning hours of Christmas 1906. At the time, the building was occupied by a number of commercial tenants, including a fruit store, bakery, lunch room, a boot and shoe store, a cigar shop and restaurant, and a barber shop. In addition, there were several residents living in apartments on the upper floors. The fire gutted the Brown Block, but there was no loss of life, and the building was ultimately repaired.

Just to the right of the Brown Block is the Elks Block, which was built in the late 1880s or 1890s. By the time the first photo was taken it had a variety of tenants, as shown by the assortment of signs on the front of the building. These included a restaurant, a boot and shoe store, a drugstore, and a photographic studio. However, like its neighbor, this building would also be damaged by a fire. It was one of several buildings that burned on March 26, 1912, in the same fire that also destroyed the Hotel Windham. The building was gutted and the roof was destroyed, but it was subsequently rebuilt.

Today, more than a century after the first photo was taken, this scene still looks largely the same. The exterior of the Brown Block is particularly well-preserved, and even the ground-floor storefront has retained its original appearance. The two lower floors of the Elks Block also look the same today, although the ornate cornice at the top of the building is gone, having been replaced after the 1912 fire. The exterior of the third floor was also probably rebuilt after the fire, which would explain why the bricks are a different shade than the lower floors. Aside from the Brown Block and Elks Block, the other two buildings in this scene are also still standing today, and all four properties are now part of the Bellows Falls Downtown Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.