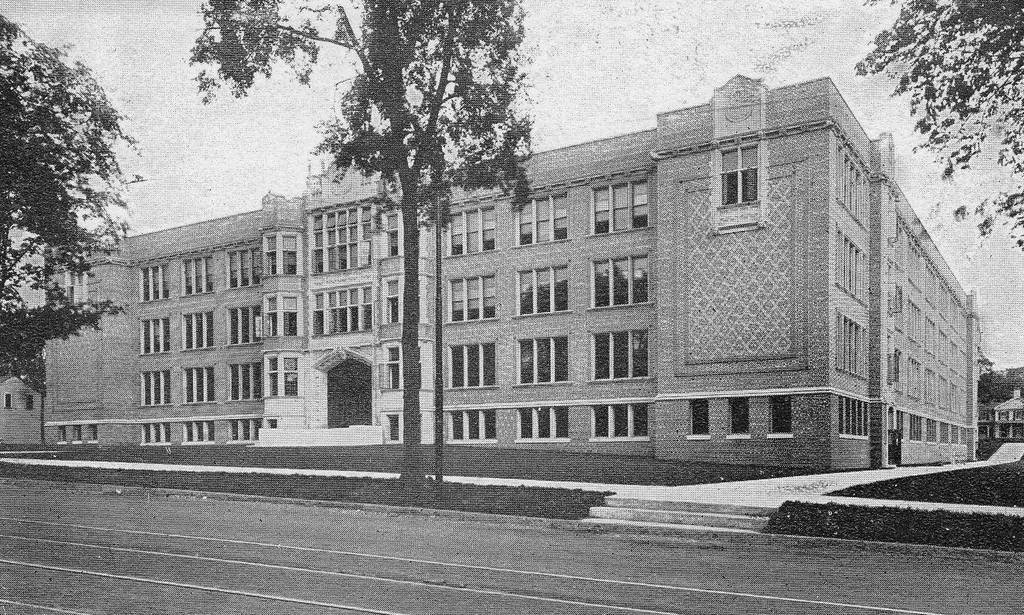

The house at 69-71 Walnut Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

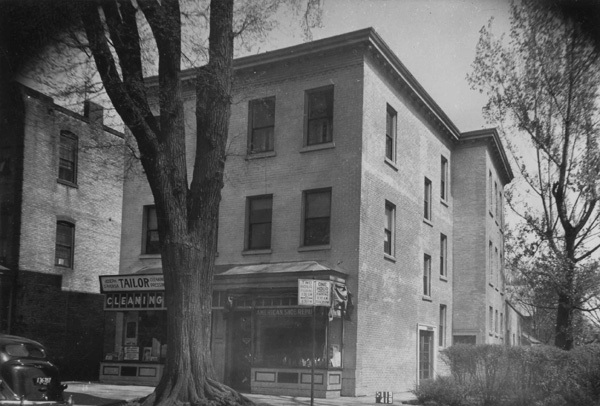

The house in 2019:

This house was apparently built around 1900 by Dennison O. Lombard, an iron foundry foreman who had previously lived in an earlier house on this lot. Lombard had acquired the property around 1889, after the death of its prior owner, Elisha D. Stocking. He lived there for about a decade before building the current house, which features a Queen Anne-style exterior that was popular for Springfield homes during the late 19th century. The lot also includes a smaller house, visible behind and to the left of the main house. This may have been built at the same time, but it is also possible that it is actually the original house, which could have been moved to the rear of the property when the new one was built.

During the 1900 census, Lombard was 54 years old, and he was living here with four of his children and his father. He was listed as being married at the time, but his wife was evidently not living here. They may have been separated for some time, because Lombard’s name appears in the newspaper archives in 1895, when his wife Nellie sued him for support. The census also shows butcher Alonzo A. Baker living on the property, presumably in the rear house. A year earlier, he had married his wife Ida, and by 1900 he was living here with his wife Ida and her 16-year-old daughter Elsie B. Kennedy. It was the second marriage for both Alonzo and Ida, as they had each been previously divorced, which was unusual for the late 19th century.

Lombard moves out of Springfield by 1903, and he died a year later. By the 1910 census, there were two different families living here, evidently with one in the main house and the other in the rear house. The first family was headed by Mary E. Murphy, a 48-year-old widow who lived here with nine of her ten children. They ranged in age from 7 to 24, and the five oldest were all employed. Alice was a stenographer for an ice company, Edward was a salesman for a baker wagon, Grace did office work for an art company, Samuel was a stenographer for a blank book company, and Ruth did office work for a publishing company.

The other residents on this property in 1910 were Charles and Catherine Wright, who were 48 and 37 years old, respectively. They lived here with five children, ranging from their 16-year-old daughter Grace to their three-year-old son William. The Wrights had a sixth living child who had presumably moved out already, and they also had three other children who had died young. Charles was the only person in the household who was employed, and he worked down the hill from here at Smith & Wesson.

By the early 1910s, this property was sold to Mary C. Gerrard, an Irish immigrant whose husband James had recently died. She lived here for several years until her death in 1915, but the house would remain in Gerrard family for many decades afterward. The 1920 census shows two of her children, Raymond and Catherine, living here, with Raymond working as an assembler at the nearby Armory.

Catherine was still living here when the first photo was taken in the late 1930s. She evidently rented rooms to lodgers, based on classified ads that frequently appeared in the newspaper during the mid-20th century, but during the 1940 census she only had one lodger, 67-year-old Florence Barker. Otherwise, she appears to have lived in the house without any other family members during this time, and she resided here until her death in 1976 at the age of 83.

Today, about 80 years after the first photo was taken, the house does not look significantly different. The buildings on the far left and far right sides of the first photo are now gone, but both the main house and the building in the rear of the property are still standing, with only minor exterior changes such as the removal of the shutters and the replacement of the porch railing.