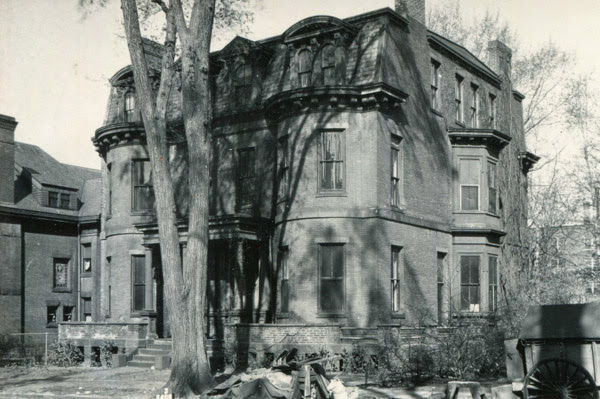

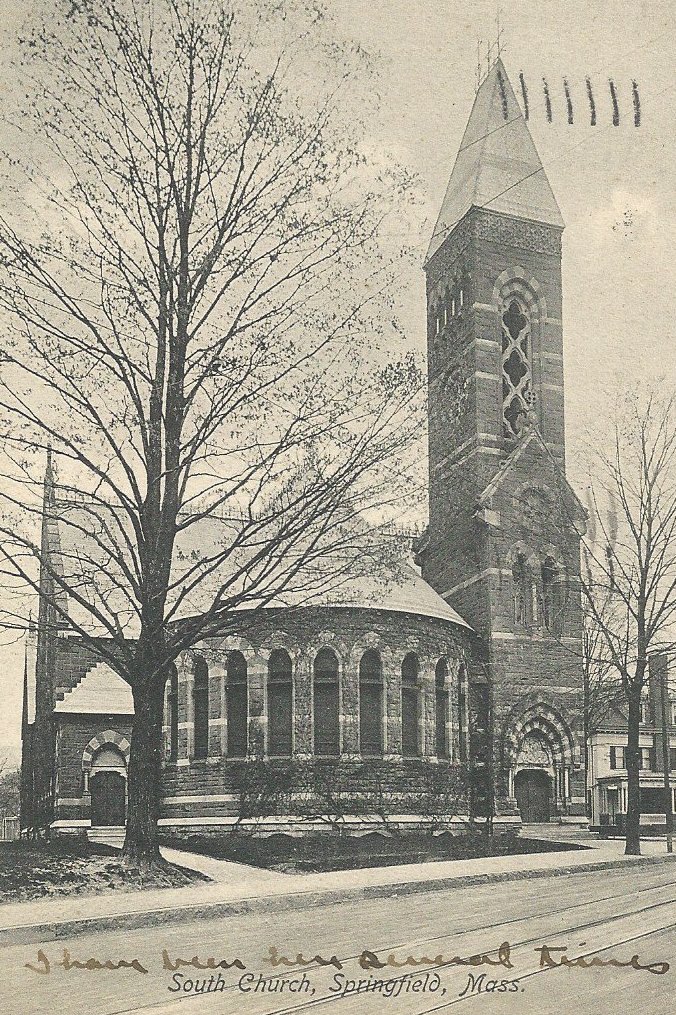

South Congregational Church on Maple Street in Springfield, around 1900-1910. Image courtesy of Jim Boone.

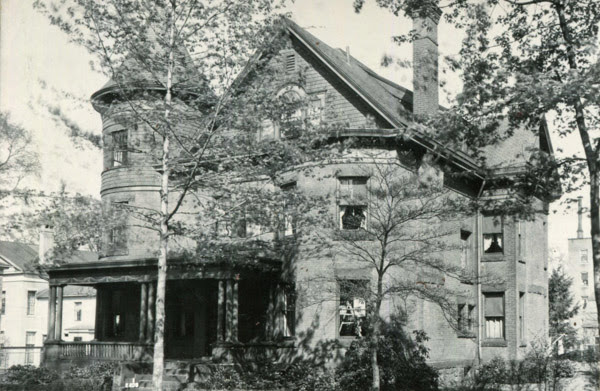

The church in 2017:

South Congregational Church was established in 1842 by members of Springfield’s First Congregational Church, and its first permanent home was on Bliss Street. This rather plain church had a very conservative architectural design that looked like any number of other churches in the area at the time, but in 1875 the congregation built a new, far larger and more elaborate church here, at the corner of Maple and High Streets.

This church was designed by William Appleton Potter, the half-brother of the equally notable architect Edward Tuckerman Potter. It was one of his first major works, and it is an excellent example of High Victorian Gothic architecture. The 1873-1874 city directory described it as being “a rather bold departure from ordinary models, being much like an amphitheater, and entirely unlike any other church building in Springfield.” This may have been somewhat of a hyperbole, since the Memorial Congregational Church in the North End, built a few years earlier, has many similar Gothic-style features, but South Congregational Church certainly stood out at a time when Springfield was building a number of fine churches.

Like many of the city’s other churches and public buildings of the era, it was built with locally-quarried stone, with a foundation of Monson granite and walls of Longmeadow brownstone. Along with this, terracotta, sandstone, and other materials were used to add a variety of colors to the exterior of the building. Also common in churches of the time period, the building is very asymmetrical, with a 120-foot tower located off-center in the southwest corner, and the main entrance at its base.

In total, it cost some $100,000 to construct, which was substantially more than most of the other new churches that were built around this time. However, the costs were offset by contributions from some of Springfield’s most prominent residents, including dictionary publishers George and Charles Merriam, railroad engineer Daniel L. Harris, and gun manufacturer Daniel B. Wesson, who later moved into a massive mansion directly across the street from the church.

At the time that this building was completed, the pastor of the church was Samuel G. Buckingham, who had served in that position since 1847. He was also an author, and he wrote a biography of his brother, William A. Buckingham, a former Connecticut governor and U.S. Senator. Reverend Buckingham remained here at the church for 47 years, until his retirement in 1894. His successor was Philip Moxom, who, aside from his work here at the church, was also the president of the Appalachian Mountain Club.

More than 140 years after its completion, South Congregational Church is still an active congregation, and the building survives as one of Springfield’s finest architectural works. The only major change over the years was the addition of a parish house on the back of the church in the late 1940s. Not visible from this angle, it matches the design of the original building and it was even constructed with brownstone that had been salvaged from the demolished First Baptist Church. The church is now part of the city’s Lower Maple Local Historic District, and in 1976 it was also individually listed on the National Register of Historic Places.