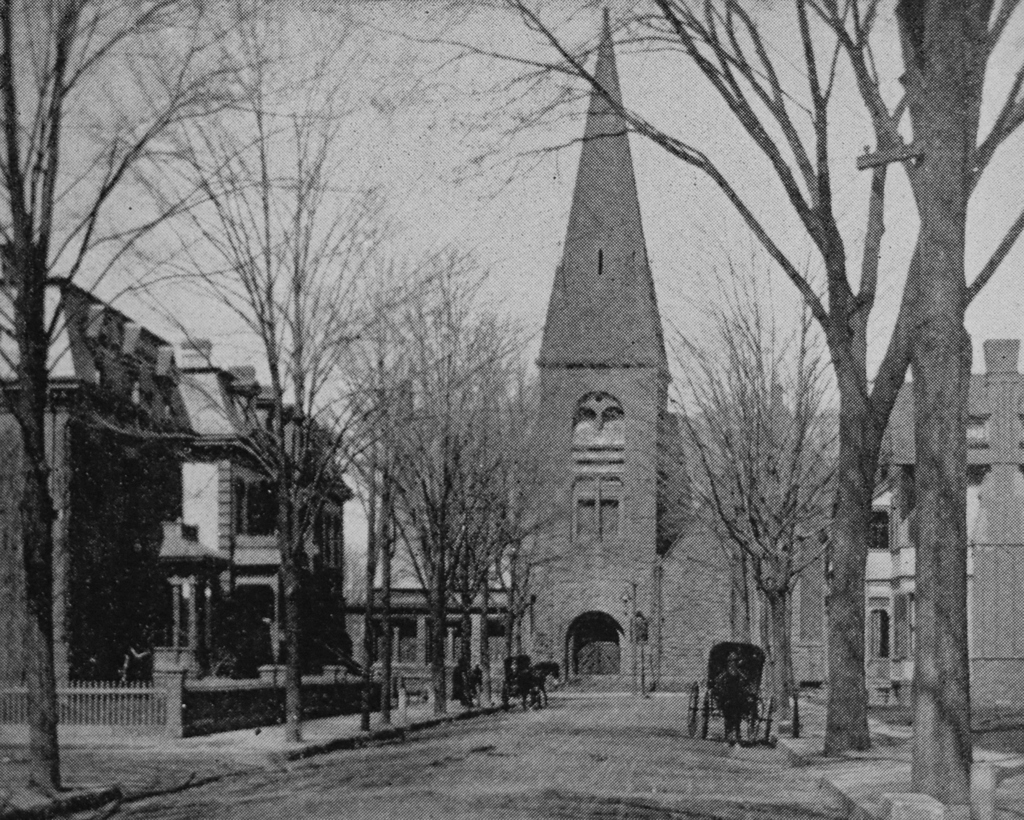

Looking north on Willow Street in Springfield, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

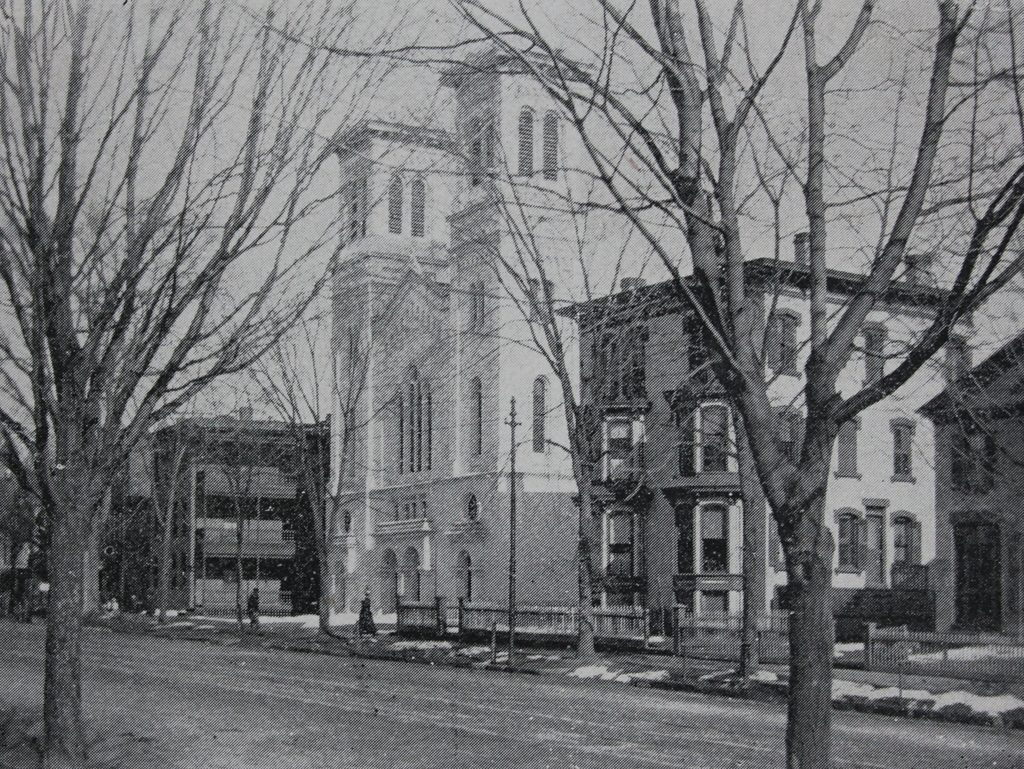

Willow Street in 2023:

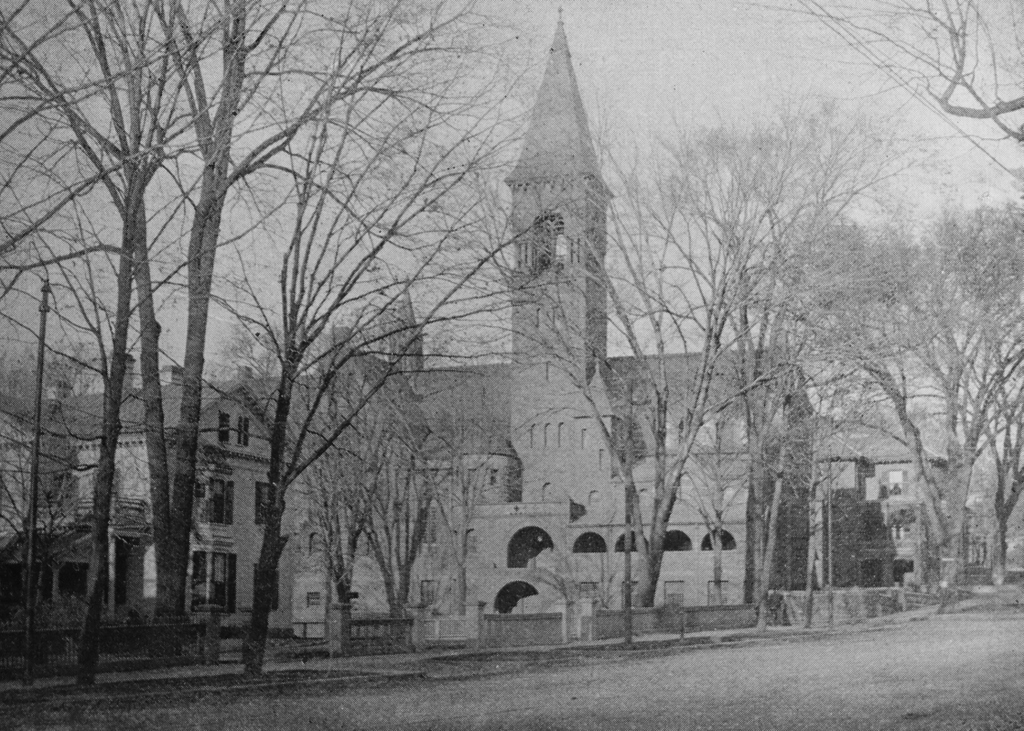

When the first photo was taken, the building on the right was the headquarters of the Milton Bradley Company, which had been founded in Springfield in 1860 as a lithograph company. Its owner, Milton Bradley, soon switched to board games, beginning with The Checkered Game of Life in 1860. By around 1880-1881, the company built this factory on Willow Street, as seen on the right side of the photo. This is the oldest part of the facility, which was soon expanded as demand increased. By the early 1900s, the company owned the entire block between Park, Willow, and Cross Streets, with its buildings almost completely surrounding a central courtyard.

Aside from Milton Bradley, this section of downtown Springfield was once home to several other factories. On the other side of Cross Street from the Milton Bradley factory was Smith & Wesson, whose factory also occupied an entire block. None of the buildings are visible in the first photo, but the brick and concrete building just beyond the Milton Bradley building was built by Smith & Wesson in the early 1900s.

Today, all of the houses on the left side of the photo are gone, and the lots are now used for parking. Smith & Wesson moved its factory to a different location in Springfield in the mid-1900s, and around the same time Milton Bradley moved to nearby East Longmeadow. Most of the Smith & Wesson buildings are gone now, except for the one in the distance of the 2015 scene. The Milton Bradley buildings are still standing, though, and along with the Smith & Wesson building they have since been converted into apartments.