Looking west on Marlborough Street from Farewell Street in Newport, around 1911. Image courtesy of the Providence Public Library.

The scene in 2017:

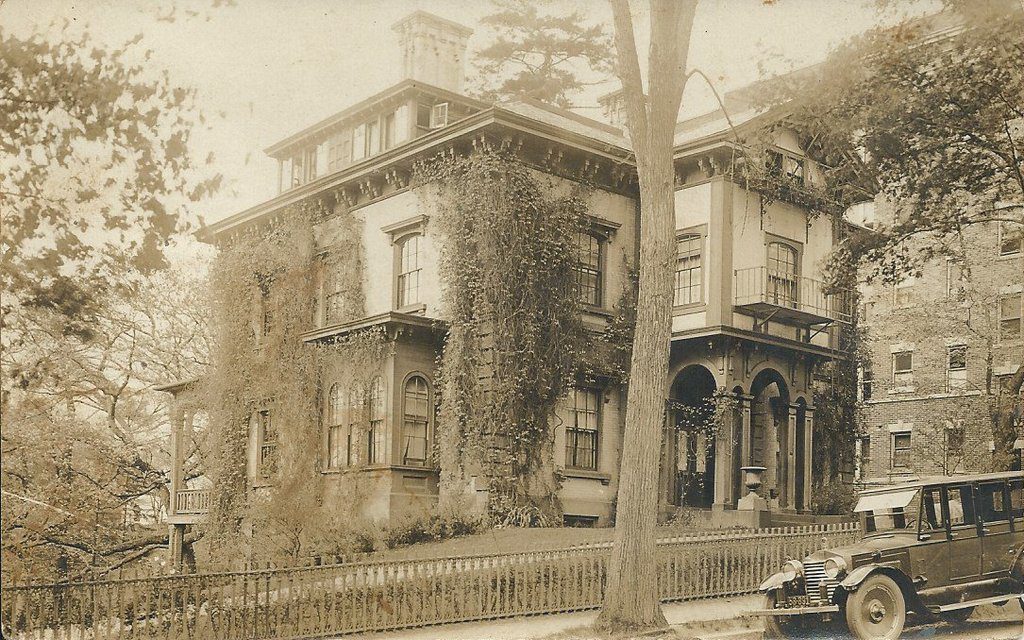

This scene on Marlborough Street includes several notable Newport landmarks, with the most significant being the White Horse Tavern on the far right. This building is perhaps the oldest in the city, dating back to before 1673. It was just a two-story, two-room house at the time, but it was later expanded, and by 1687 it was being operated as a tavern by William Mayes, Sr. His son, William Mayes, Jr., had a career as a pirate before returning to Newport, retiring from piracy, and taking over the operation of the tavern in 1703. Within a few years, though, his sister Mary and her husband, Robert Nichols, owned the property, and it would remain in the Nichols family for nearly two more centuries.

In the years before the Colony House was built in the 1730s, the colonial legislature often met here at the White Horse Tavern, which acquired its current name around this same time. Some 40 years later, it was used to house British soldiers during the American Revolution, and after the war the building was expanded to its current size, including the addition of the large gambrel roof. It would continue to be owned by the Nichols family until it was finally sold in 1895. The first photo was taken only about 16 years later, and at this point it had been converted into a rooming house.

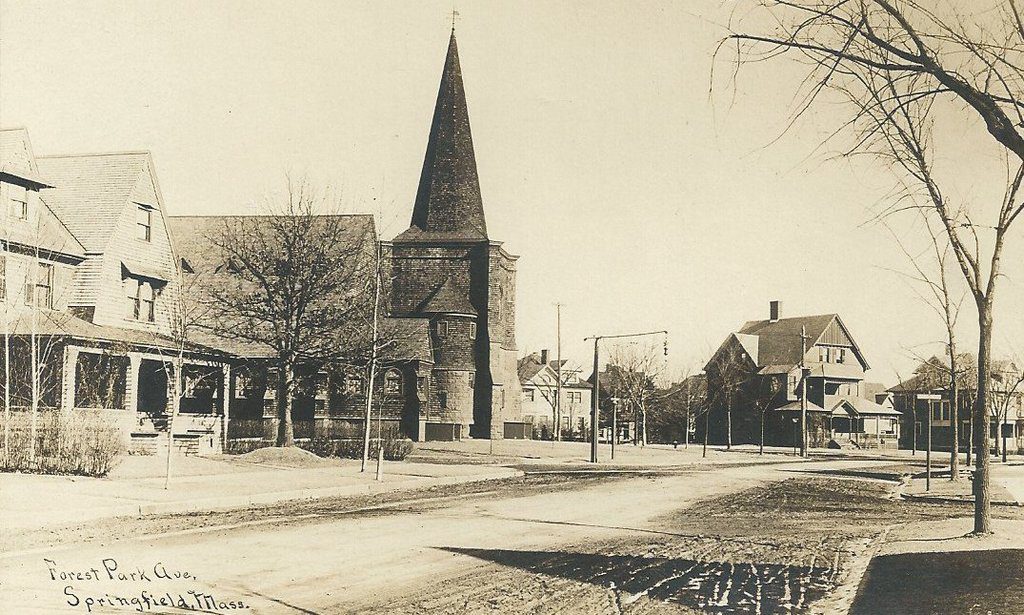

The White Horse Tavern was already an old building in 1807 when the other prominent landmark in this scene, St. Paul’s Methodist Church, was completed. Long known for its religious tolerance, Rhode Island was among the first places where Methodism took root in America in the late 18th century. However, the Newport congregation caused a considerable stir in the Methodist community when they built this church. Although similar to other New England churches of the era, it was far more elaborate than the plain meeting houses that early Methodists worshipped in. It is considered to be the first Methodist church in America to have a steeple, bell, and pews, and early Methodist leader Bishop Francis Asbury is said to have “lifted his hands with holy horror when he first saw it and predicted that a church which began with a steeple would end with a choir and perhaps even an organ.”

Bishop Asbury was ultimately proven right in his prediction about the organ, with the congregation installing one in the church in the 1850s. However, an even more significant change had come about 15 years earlier in 1842, when the entire building was raised eight feet and a new, full-story foundation was built beneath it to make space for a parish hall. Otherwise, the exterior of the church has not significantly changed, although the building was heavily damaged by a fire in 1881. However, it was subsequently restored, and the first photo was taken about 20 years later.

In more than a century since the first photo was taken, most of the historic buildings on both sides of Marlborough Street have been demolished. Even the White Horse Tavern itself was threatened with demolition. Badly deteriorated and neglected more than 50 years after it became a rooming house, it was nearly demolished in the 1950s to build a gas station here on the corner. Instead, though, it was purchased by the Preservation Society of Newport County, who restored it and reopened it as a tavern in 1957. It remains in operation today, and is marketed as America’s oldest tavern. Further down the street, St. Paul’s Methodist Church is also still standing, and still houses the same congregation. The 2017 photo shows it in the midst of a restoration project, but otherwise it is largely unchanged from the first photo, and both it and the White Horse Tavern are now contributing properties in the Newport Historic District, which is a National Historic Landmark district.