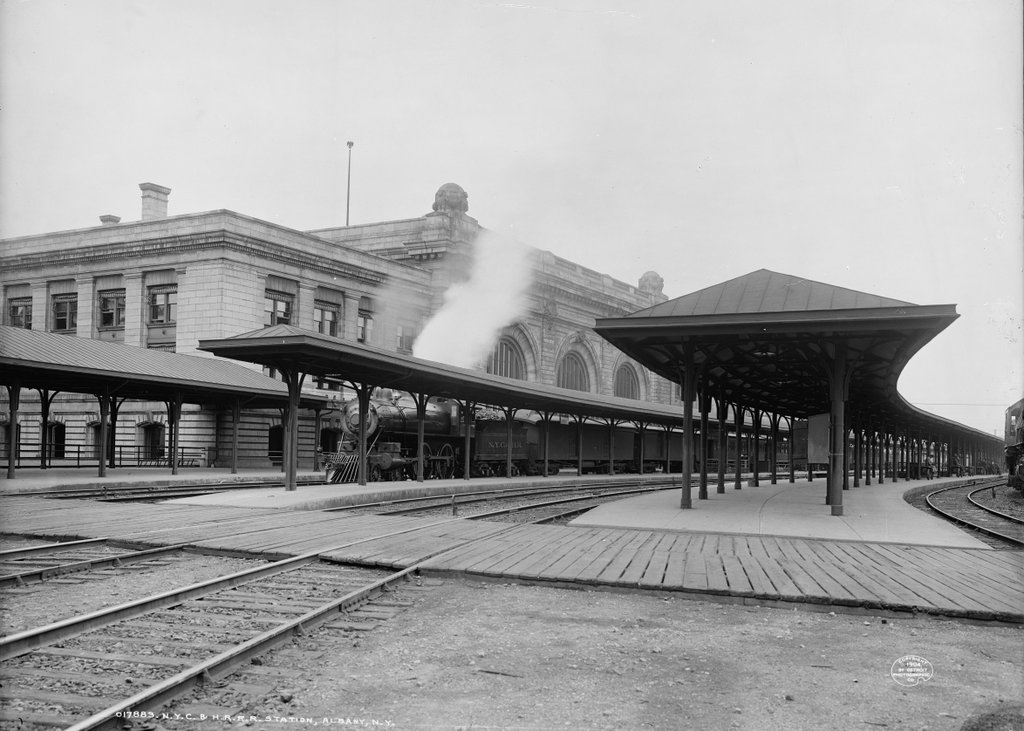

The platforms on the east side of Union Station in Albany, around 1904. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2019:

Taken nearly 120 years apart, these two photos capture one of the ways in which transportation changed in the United States over the course of the 20th century. The first photo shows a large, recently-completed downtown railroad station, with several trains waiting on the tracks and a group of people on one of the platforms. However, in the present-day scene the railroad station has been converted into offices, while the tracks and platforms are completely gone, replaced with a parking garage. Another even larger parking garage stands in the distance on the right side, and further to the right, just out of view, is an interstate highway.

Albany’s Union Station was completed in 1900, and it was primarily used by the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. However, it was also used by the Delaware and Hudson Railway and the New York Central-controlled West Shore Railroad, and it was the western terminus of the Boston and Albany Railroad, which the New York Central had begin leasing earlier in 1900. The station building featured a granite, Beaux-Arts exterior, and it was designed by the prominent Boston architectural firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge. This firm was particularly well-known for their railroad stations, and they designed a number of them for the Boston and Albany, including Union Station in Springfield and South Station in Boston.

The station was built at the corner of Columbia Street and Broadway, with the main entrance on the western side, facing Broadway. However, this view shows the other side of the station, looking north from the southern end of the platforms. Here, three large island platforms were situated between the tracks, and passengers could access them via two underground tunnels. The train on the left side of the first photo is a New York Central passenger train, with 4-4-0 locomotive number 1135 in the lead. Another unidentified locomotive stands on the far right side of the photo, and further in the distance just to the left of that train is a group of men—possibly railroad employees—leaning against and sitting on a row of baggage carts. These trains were just two of the 96 daily trains that served Union Station when it first opened at the turn of the 20th century. Of these, there were 42 New York Central trains, 31 Delaware and Hudson, 13 West Shore, and 10 Boston and Albany.

Passenger rail travel continued to increase nationwide throughout the first half of the 20th century, eventually peaking during World War II. This was also the busiest time for passenger trains in Albany, with 121 daily trains here at Union Station. However, the postwar period saw a sharp decline in ridership, a problem exacerbated by the development of the Interstate Highway System starting in the 1950s. By the 1960s, many of the railroad companies that had dominated the nation’s economy a half century earlier were now teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. As a result, the New York Central merged with its longtime rival, the Pennsylvania Railroad, in 1968, forming the Penn Central Railroad.

For nearly a decade prior to the merger, the New York Central had been looking to rid itself of Albany’s Union Station, which was under-utilized and expensive to maintain. The station was also near the path of the planned Interstate 787, which would cut through part of the station’s passenger yard. Soon after the formation of Penn Central, the newly-formed railroad opened a new, much smaller passenger station directly across the river from here in Rensselaer, and the old Albany station was unceremoniously closed on December 29, 1968.

A few months later, the New York Times published an “obituary” of the station, titled “In Melancholy Memory of Albany’s Union Depot.” The article lamented the closure of the grand station, recalling its long history during the heyday of passenger trains and contrasting its architecture with that of the new station, which was described as a “one-story crackerbox of concrete blocks.” At the time, the fate of the old station was still undetermined, but the article mentioned several different proposals, which ranged from converting it into a museum to demolishing it and building a high-rise luxury apartment building and marina on the site.

Ultimately, neither of these proposals materialized, and the building was instead converted into offices in the 1980s. It was originally the home of Norstar Bancorp, and it was initially named Norstar Plaza, although it was subsequently renamed Peter D. Kiernan Plaza after the death of the bank’s president. The bank then went through a series of mergers, and over the next two decades the building was home to Fleet Financial Group, FleetBoston Financial, and then Bank of America. The building was used by Bank of America until 2009, and it now serves as offices for several other companies.

Overall, the present-day scene is drastically different from the view in the early 20th century. The most dramatic change is the parking garage in place of the station tracks and platforms, but other changes have included the tall building just beyond the station on the other side of Columbia Street. However, the station itself has not seen many exterior changes since the first photo was taken, even though much of it is hidden by trees from this angle. Today it stands as an excellent work of Beaux-Arts architecture, and it also serves to highlight the benefits of historic preservation and adaptive reuse.