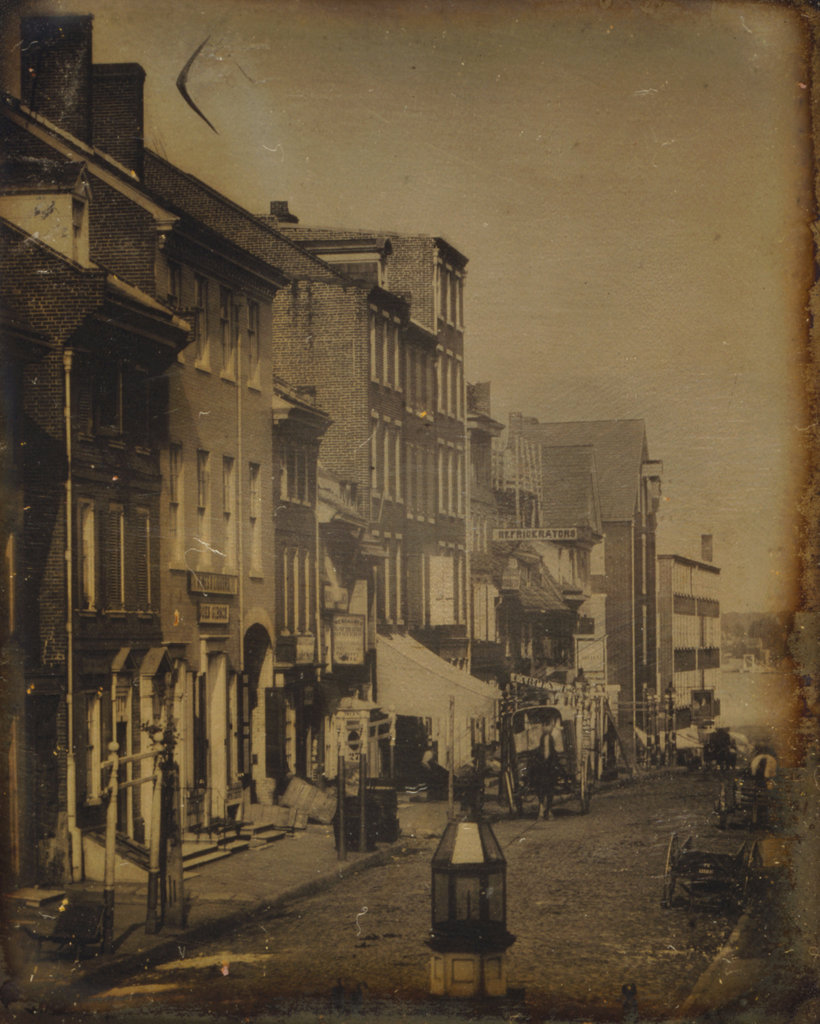

The view looking east on Chestnut Street, between Second and Letitia Streets in Philadelphia, around 1842-1845. Image taken by William G. Mason, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The scene in 2019:

As with the image in the previous post, the first photo here was taken by William G. Mason, in the early years of photography. It was possibly taken on the same day as the image in the other post, and it shows a similar scene; it was taken only about 50 yards east of the other photo. However, unlike that photo, which is a photograph of the original image, this photo here is the original daguerreotype taken in the 1840s, so it has a much higher image quality.

The first photo here shows a mix of commercial buildings on the north side of Chestnut Street, extending all the way down to the Delaware River in the distance. Most were likely built in the early 19th century, although it is possible that some of them, especially the shorter ones, might date back to the 18th century. Several signs are legible, including two on the three-story brick building on the left with the arched doorway. As indicated by the signs, this building was occupied by wine and liquor dealer John Gibson. Further to the right, the small two-story building has a partially-legible sign advertising lunch and oysters, and even further in the distance is a sign that reads “Refrigerators.” This likely referred to ice boxes, which became popular during this period due to the growth of the commercial ice industry in the United States.

Just a few years after the first photo was taken, the building on the left suffered a fire that destroyed much of John Gibson’s liquor business. The fire, which occurred on the morning of September 26, 1846, started in the distillery in the rear of the property. According to contemporary newspaper accounts, some of the liquor boiled over, igniting nearby flammable materials and spreading to the building here on Chestnut Street. Firefighters were able to contain the fire, which did not fully engulf this building or spread to its neighbors. However, Gibson’s still was almost entirely destroyed, as was some of the liquor that he was producing.

Today, nearly 180 years after the first photo was taken, the streetscape here is not dramatically different. This block of Chestnut Street is still lined with historic 19th century brick commercial buildings, and even the street itself is still paved with cobblestones. However, the buildings themselves are different; all of the ones from the first photo appear to have either been demolished or heavily altered at some point in the 19th century. Based on their ornate facades, the brick building on the left and the two just to the right of the center are clearly from the late 19th century, and the one that is partially visible on the extreme left was built in the early 20th century. The only possible survivors from the foreground of the first photo are the two matching five-story buildings in the center of the 2019 photo. They have similar architecture to the ones in the first photo, it is possible that one or both of these might have been built in the first half of the 19th century and subsequently altered.