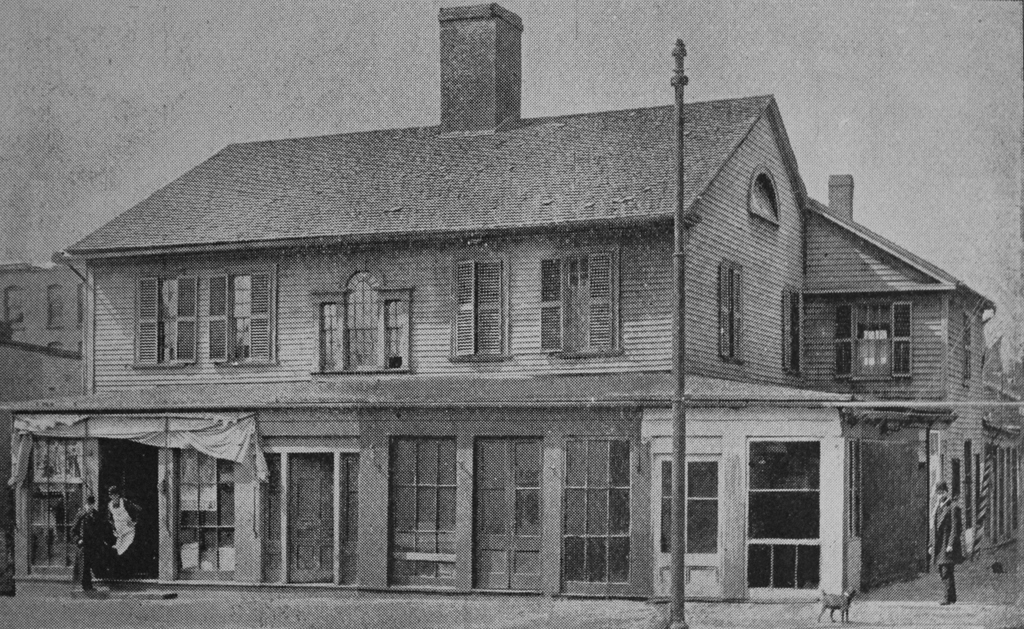

The Hampden County Jail on State Street in Springfield, Mass, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The scene in 2019:

Throughout the colonial period, Springfield was the seat of Hampshire County, and consequently it was home to both the county courthouse and the jail. However, the town was located in the southern part of the county, which at the time included all of present-day Hampden, Hampshire, and Franklin Counties, and by the 1790s Springfield was only its sixth-largest community. So, in 1794 the county seat shifted to Northampton, which was both larger and more centrally-located than Springfield.

The old jail had been located on Main Street in the South End, on the current site of the MGM casino. It was in use from the late 1600s until 1794, and it was subsequently sold to a private owner, who used it until the early 19th century, when it was demolished to open Bliss Street through the property. In the meantime, though, Springfield again became a county seat in 1812, when the southern third of Hampshire County was partitioned off, becoming Hampden County. With the old jail unavailable, this meant that the new county would need to construct a new facility here in Springfield.

The location selected for this new jail was here on State Street, on the site of what later became Classical High School. At the time, this section of Springfield was still only sparsely developed, with most of the downtown area centered along the Main Street corridor, and the county purchased the one-and-a-half acre property in 1813 for just $500. It then built the jail here, which was completed in 1815 at a cost of $14,000. This jail would be steadily expanded over the years, but it remained in use throughout most of the 19th century, and it is shown here in the first photo, which was probably taken shortly after it closed.

The first inmate here was David Cadwell, a Wilbraham resident who had been arrested for assault on June 17, 1815. His stay was short, though, because he paid his fine and court costs and was released on the same day. Other prisoners had different means of leaving, including Jesse Wright of Springfield, who became the first to break out of the jail when he escaped on February 12, 1816.

Aside from confining prisoners, the county jails of Massachusetts were also used for executions during the 19th century. These were rare occurrences here in Springfield, and the first person sentenced to death in Hampden County was Robert Bush of Westfield, who murdered his estranged wife Sally on September 29, 1827. At the time, she and her two children had been living with another family, and Bush went to this house, shot her with a shotgun, and then attempted suicide by overdosing on opium. He was saved when someone administered an emetic, but Sally died four hours later. The trial was held a year later at the Springfield courthouse, and Bush was found guilty and sentenced to death. His execution was set for November 14 here at the jail, but he managed to obtain opium a second time, and committed suicide on the night of November 12.

The first execution that was actually carried out here at the jail was that of Alexander Desmarteau of Chicopee, who was hanged on April 26, 1861 for the 1858 rape and murder of seven-year-old Augustine Lucas. He was among the first to be tried under the state’s new law that created different degrees of murder, and his lawyers appealed the case, arguing that the law was unconstitutional. This delayed his execution until his case reached the Supreme Judicial Court, which upheld his conviction of first degree murder.

The execution occurred here in the prison yard, which appears to have been the area on the right side of the building in the first photo. About 125 people were allowed into the yard to witness the execution, including most of the city and county officials, but many more spectators attempted to view it from outside the prison walls by climbing to the tops of nearby buildings. During his time in jail, Desmarteau had converted from Catholicism to the Episcopalian faith, and the Reverend George H. McKnight of Christ Church accompanied him and preached a sermon here prior to the execution. He spoke on the grievous nature of Desmarteau’s crimes, along with his subsequent remorse and religious awakening, and Desmarteau was then given the opportunity to say his last words, which were reported by the Springfield Republican as “I don’t know as I desire to say anything, except to bid you all farewell. I hope to meet you all in a better world.”

Another condemned criminal who was executed here was Albert H. Smith of Westfield, whose 1873 execution made headlines in newspapers across the country. The previous summer, 22-year-old Smith had been working as a switchman for the Boston & Albany Railroad when he met 25-year-old Jennie Bates. He soon fell in love with her, and according to Smith they were engaged to be married. However, Jennie claimed that they were only acquaintances, and by the fall of 1872 she was engaged to 40-year-old Charles D. Sackett. Believing that he had been betrayed, Smith shot both of them on the evening of November 20, 1872, while the couple was walking home together after watching a play. He shot Jennie three times, including once in the head, and Charles was hit once, with the bullet puncturing his lung. Despite her injuries, Jennie made a full recovery, and Charles seemed to be improving until infection set in, and he died 13 days after the shooting.

Smith’s lawyers used the insanity defense, arguing that, in his mind, he and Jennie were married. Because of this delusion, he believed that his actions were those of a jealous husband trying to save his marriage, rather than an act of revenge perpetrated by a spurned lover. The argument seemed persuasive to many spectators at the trial, but the jury nonetheless found him guilty of first degree murder, and the death sentence was carried out here on June 27, 1873.

In the hours before his execution, Smith apparently showed no emotion or regret, with the Republican observing that “His eye was bright, his manner easy and cordial,” and “it was hard to realize that he was the one most interested in the approaching execution and had scarce an hour to live.” The only hint of emotion came in the form of a slight tremor in his voice, when he spoke of Jennie. He spoke at length to the newspaper reporter, who wrote about his cell here in the jail in his account of the execution:

His cell had the same neat and almost pleasant appearance that it has always worn since he has been its occupant. The narrow but tidy bed occupied the whole of the right side, a small stand filled the niche and the head, while a common stool in the front corner nearest the office completed the furniture of the narrow apartment. But the walls were tastily brightened with a number of pictures cut from illustrated papers, arranged by Smith, while the stand was almost hidden by the beautiful floral offerings, some of which came from ladies in this city and Westfield, who had never seen the unfortunate man. Half-hidden in the midst of these, and yet plainly visible from the door, was placed a photograph of the girl, and the frequent glances of the prisoner to it proved that he considered it the chief ornament of the room.

The reporter then went on to contrast this with the grim realities of the day, which Smith seemed oblivious to:

At the lower extremity of the corridor, and in plain view from the cell, stood the gallows, with the fatal noose dangling in the air. Just opposite the prisoner, across the landing, sat Turnkey Norway, who for 36 hours has remained constantly at his post, while directly above the latter’s head a clock was heartlessly ticking off the last moments of the doomed man’s life. Further on was the open grating leading to the office, and behind this jostled a crowd of curious reporters, eager to get one glimpse at the murderer or to catch a single syllable of his last words. But he paid no attention to them, and was equally unmindful of the gallows. His pleasant eyes were turned toward his caller, whom—as always when talking with any one—he looked straight in the face, and with whom he conversed freely, calming and interestingly.

During the interview, Smith expressed that the only thing bothering him was the fact that he would not be able to see Jennie one more time before his death. Even then, he was not bitter. He evidently believed that she truly wanted to be there, and regarding her absence he said, “But I don’t blame her. There is too much influence to keep her away. And yet, I think she ought not to be so much influenced by them. But I have her picture and a lock of her hair in my pocket, and they will be buried with me.”

Smith remained calm and composed throughout the execution proceedings. The jail chaplain, Reverend William Rice, read a passage from Psalm 51, which was followed by the singing of a hymn and then a prayer. Smith then spoke for about three minutes, reiterating his earlier statements about Jennie and had not acted out of revenge when he killed Sackett. He ended with “Farewell. Farewell,” which, according to the Republican, was “uttered in a clear, loud voice, and without a perceptible tremor.”

The reporter went on to describe how “Then followed the strange, sad spectacle of a man, standing in the very shadow of death, madly kissing the picture of the woman he had loved, to his ruin.” The picture was then returned to his pocket, to be buried with him, and his legs were bound, the rope adjusted, and a hood placed over his head. The sheriff then shook his hand, and he was executed at 10:44 a.m., with the rope breaking his neck and killing him instantly.

At least one other execution took place here at the jail in 1883. The prisoner, Joseph B. Loomis of Southwick, had been convicted of the December 1, 1881 murder of David Levett in Agawam. Loomis, who was about 22 at the time, had been a childhood friend of Levett, and the two had gone to school together. From there, however, their paths had diverged, with Levett becoming a successful shopkeeper in Springfield, while Loomis worked as a laborer and had, according to the Republican, had “a fondness for drink” and “had “long borne an unenviable reputation.”

On the day of the murder, Loomis visited his friend at his confectionery shop on Main Street in Springfield. The two spent much of the evening together, and at some point Loomis devised a plan to rob and kill his friend. He deliberately stayed until after the last train home had left Springfield, and then asked Levett if he could hire a carriage to bring him home. Levett agreed to do so, and even offered to accompany him, which Loomis had evidently counted on him doing.

They left Springfield sometime after 9:30 p.m., with Levett driving the carriage. As they were crossing the covered bridge over the Westfield River, where the sound of the wagon wheels on the planks would drown out any noise, Loomis produced a pistol and shot Levett in the head. He then covered up Levett’s body and rode to a deserted area, where he took all of his friend’s valuables before abandoning the carriage and the body.

The body was found the next day, and Loomis soon became the prime suspect, since he had been the last person seen with Levett. He was found to be in possession of one of Levett’s gloves, along with a handkerchief. These items would later become significant when, about four months later, Levett’s gold watch was found on the side of the road in Westfield, wrapped in a matching handkerchief and glove. Loomis had evidently placed it there for safekeeping, intending to return later for it, but at the trial he claimed that Levett had given it to him to take to Westfield for repairs, and that he must have lost it along the way. The jury was apparently skeptical of this explanation, and he was found guilty of murder, largely on the basis of this circumstantial evidence.

The execution took place on March 8, 1883, here at the Hampden County Jail. He ate veal steak for his last meal, and then spent much of the morning writing farewell letters to friends. On the gallows, he read a prepared statement for his last words, in which he confessed to the crime and asked for forgiveness. He thanked the officers at the jail for their kindness, and he concluded by declaring, “Let it be known to you all, and to coming generations, that rum nerved my arm to strike down my friend David Levett, and has been the inspiration of what has been wicked in my career to the gallows.”

By the time of Loomis’s execution, the jail was nearly 70 years old, and despite several additions over the years it was very overcrowded. King’s Handbook of Springfield, published in 1884, noted that some prisoners had to be sent to neighboring counties because of the conditions here, and declared that “The county is indictable for not providing better accommodations, and the time is not far distant when a new jail must be built.”

Two years later, the Republican expressed similar concern in an exposé titled “Certain Facts About the Jail.” In this article, the newspaper revealed that the prison contained 116 cells for men and 28 for women, yet at the time its inmates included 175 men and 27 women. The additional 59 men were housed in various makeshift quarters, including 15 who lived in a 250-square-foot attic space with just one window and no ventilation. Elsewhere in the jail, the small hospital room has 17 inmates, with the healthy and sick sleeping side-by-side, and another 22 were kept in poorly-ventilated room that measured less than 300 square feet.

Aside from the overcrowded conditions, the newspaper also noted the poor sanitation, writing:

About 100 of the men confined in the house of correction are employed in a work-room 50 by 60 feet square, making cane-chair seats; and here also, the breathing-room is pitifully inadequate. . . . Every week they have to take a bath, but there are only two bath-tubs, and two men have to go through the same water and sometimes four. The prisoners march down the hall each morning to the closet with soil-buckets in hand. These are emptied into a funnel connecting directly with the sewer and though the iron doors are closed the stench is fearful; the more so as it is added to the foulness of the air that results from overcrowded sleeping apartments. A man is employed all the time in whitewashing the walls, but that is a pitifully inadequate provision for sanitation. . . . The law requires that jail inmates shall be given access to the open air. This is out of the question on the present premises; the men have no yard, the women have a kind of pit, only open toward the sky, and usually hung full with washing.

The interior of the prison was not the only source of complaints during the 1880s, though. By this point this section of State Street had gone from being on the outskirts of downtown to becoming the cultural center of the city. As a result, the jail had become increasingly out of place here. It was directly across State Street from St. Michael’s Cathedral, adjacent to the high school, and its other neighbors included the Church of the Unity, Christ Church, and the city library, along with a number of fine homes. Overall, the jail was an unwelcome relic from an earlier era, and according to King’s Handbook it was “an inharmonious object in an otherwise pleasing view.”

The jail ultimately closed in 1887, upon the completion of the York Street Jail along the banks of the Connecticut River in the South End. The building was then used temporarily as a militia armory, until the completion of a new armory on Howard Street in 1895. At some point in the next few years, the old building was then demolished, and the land became the site of a new high school building, which was completed in 1898 as Central High School. Later renamed Classical High School, the building was converted into condominiums after the school closed in 1986, and it is still standing here today.

In the meantime, the York Street Jail served as the county jail for over a century, even longer than its predecessor here on State Street. However, it ultimately faced the same problems of overcrowding. Originally designed for 256 inmates, it had more than 700 by the 1980s, leading to repeated calls from Sheriff Michael Ashe for a new facility. Faced with apathetic bureaucracy, in 1990 Ashe took the drastic step of commandeering the National Guard armory on Roosevelt Avenue in order to house prisoners. To do so, he invoked an obscure 17th century law that empowered sheriffs to take necessary actions in the event of “imminent danger of a breach of the peace.” Given the dangerously overcrowded conditions at the jail, he argued that there was such an imminent danger. His actions quickly earned him national attention, highlighting a problem that state officials had long ignored, and it ultimately lead to the construction of the present Hampden County Correctional Center in Ludlow, which opened in 1992.