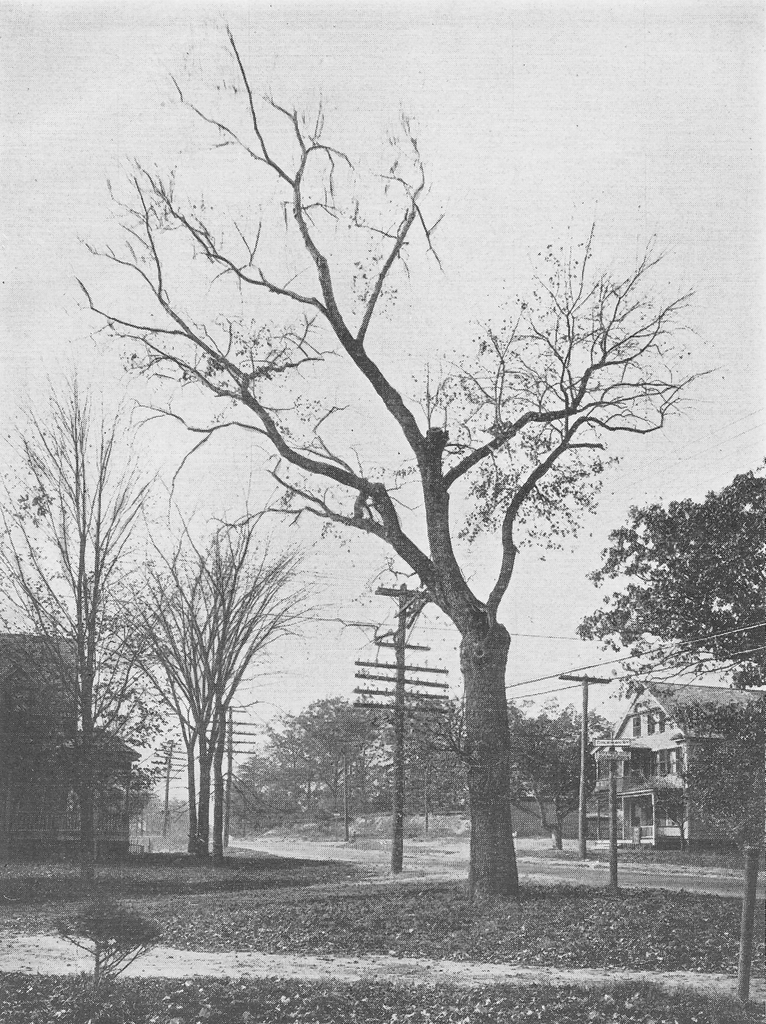

Looking west on Boston Road from near the corner of Coleman Street in Springfield, around 1924. Image from Catalogue of the Flowering Plants and Ferns of Springfield Massachusetts (1924).

The scene in 2019:

The primary subject matter of the first photo was intended to be the tree in the foreground, which is identified as Acer rubrum L. var. tridens Wood, a rare variety of red maple. However, the photo also captures a rare view of Boston Road as it appeared nearly a century ago, prior to its extensive commercial development. The view faces west along Boston Road from the corner of Coleman Street, right in the midst of what would soon become the center of the Pine Point neighborhood.

Throughout most of the 19th century, this section of Springfield was only sparsely settled, with the 1870 city map showing fewer than 20 houses along the entire 3.5-mile stretch of Boston Road from Berkshire Avenue to the Wilbraham town line. This began to change by the 1890s, though. Likely motivated by the recently-opened trolley line on nearby Berkshire Avenue, landowners in present-day Pine Point began subdividing their properties with new streets and house lots. By 1899 there were at least six houses on Coleman Street, and over the next two decades there would be further development, particularly on Denver and Jasper Streets.

Overall, though, the neighborhood maps of the early 20th century show far more vacant lots than houses, and it would take many years before most of the streets were fully developed. The first photo was taken during this period, when even Boston Road, the main thoroughfare through Pine Point, still had many empty lots and hardly any commercial development.

There are only two houses visible in the first photo. On the left, at the southwest corner of Boston Road and Coleman Street, is one of the oldest surviving houses in the area. It was built sometime around 1882, predating the modern street grid that was added about a decade later, and during the early 1880s it was the home of merchant William G. Pierce. Subsequent owners included tailor Julian Belanger, and by the time the first photo was taken in the early 1920s it was the home of civil engineer Albin M. Kramer, his wife Rose, and their three children.

The house on the right, at 168 Boston Road, is somewhat newer. It was built sometime between 1899 and 1910, and it appears to have been constructed as a two family home. During the early 20th century it had a number of different tenants, most of whom only stayed for a few years. Among these were my great grandparents, Frank and Julia Lyman, who lived here from about 1915 to 1917. Frank was a machinist who was originally from Wilbraham, and Julia grew up in New York City, where she worked for the New York World newspaper. They lived in the New York area for the first few years of their marriage, but they moved to Springfield around 1915. At the time they had two young children, Elizabeth and Edith, and their third child Evelyn, my grandmother, was born here in this house in 1917. Soon after, the family purchased a house nearby at 37 Coleman Street, and they were living there when this photo was taken at the end of their street a few years later.

By the 1920 census, one unit in the house at 168 Boston Road was occupied by painter Raymond L. Taft, his wife Alice, and their three young children. The other unit was the home of carpenter Frank E. Bowen, and his wife Edith, who had three children of their own. However, neither family appears to have remained here for very long; Alice Taft died in 1921, and by the following year Raymond was living elsewhere in Pine Point. The Bowen family had also moved out by then, and during the 1920s the house appears to have changed tenants very frequently, with most only appearing here in the city directory for one year.

Within just a few years after this photo was taken, this section of Boston Road developed into the commercial center of the Pine Point neighborhood. At some point around the late 1920s, the house on the right was altered with the addition of two storefronts, one of which was the home of Nora’s Variety Store for many years. Across the street from there, on the left side of the scene, a row of commercial buildings was constructed in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The easternmost of these, visible just beyond the house on the far left, is best known as the location of the original Friendly’s restaurant, which opened there in 1935.

Today, nearly a century after the first photo was taken, very little in this scene has remained the same. The red maple is long gone, and all of the vacant lots here have since been developed. Boston Road is now a four lane road and one of the main east-west routes through the city, and it is almost entirely commercial, with very few remaining houses. However, both of the houses from the first photo have managed to survive, although the one on the left was heavily altered by the late 1920s storefront addition. The one on the right has remained much better preserved, though, and it stands as a rare Victorian-style house in an otherwise predominantly 20th century neighborhood.